RPS has reviewed the game

I probably didn’t grow up when you did. I feel the need to get that out of the way early, because this review is largely going to be about how Ion Fury’s old-school sensibilities clash with my own. Not all of them, I should stress. Shooters have trended towards a slower pace, while I’m a nippy boy. It feels good to shoot and hop.

I’m just so unbearably lost.

I’m getting lost as Cpl. Shelly “Bombshell” Harrison, a cop who spends her days shooting at “cracked-out cyborg punks” daring to rebel against “the longstanding order of permanent martial law”. None of this particularly matters, aside from the way it means I frequently hear her bellow crass nonsense like “nothing that laying down another beating can’t solve”.

Ion’s story, as far as it has one, is told through brief monologues from a maniacal scientist who blew up your house, sometimes rebutted by Harrison’s cack-handed quips. Hardly any of it lands, but that’s almost by the by. This is all set-dressing for the running and gunning – until the set empties, and I’m left wondering where on earth I need to go next.

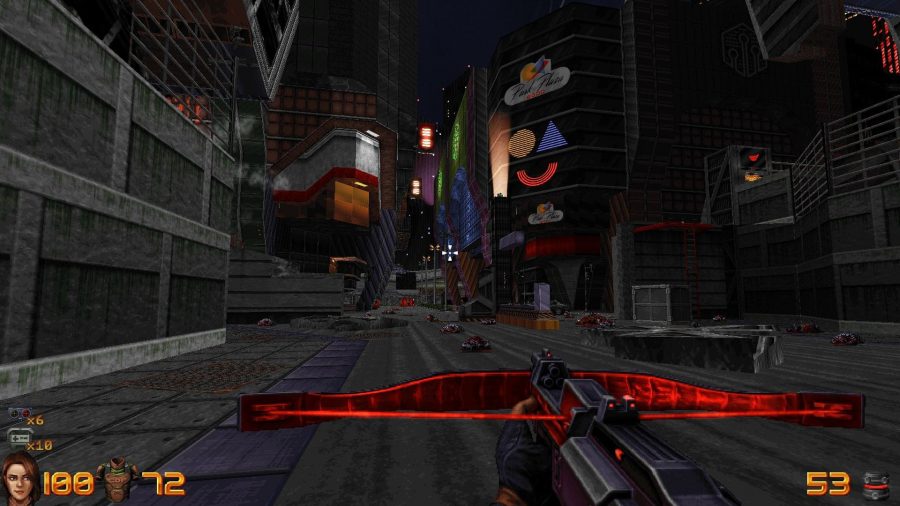

Getting lost in games sucks at my soul. I’ve spent far too long trundling around Ion Fury’s neon-dusted streets and supervillain bunkers, dipping in and out of rooms like a millennial robbed of Google Maps. Or any kind of map, as I first believed. I didn’t think to comb through the keyboard buttons in search of one, and Ion didn’t think to prompt me to. Or else (if you’ll indulge my suspicions) it deliberately decided against it.

Ion Fury revels in letting you figure stuff out for yourself. It doesn’t just let go of your hand: it jumps into a car and swans off to the south of France with a strange woman you’ve only met once. I’m aware that sounds great, refreshing even, to the eyes and ears of anyone who’s sick of following arrows that tell you exactly where you need to go. But instead of that, Ion Fury challenges observation skills I simply don’t have.

It tries to help me, sometimes. Giant, glowing signs will point me towards progress. Then I’ll follow them into a room with a vent I fail to notice, conclude that they must have been guiding towards a bonus area, and waste twenty minutes in a meandering malaise around the rest of the level. It’s not a rewarding barrier to rub up against. There’s no sense of improvement, no notion that the next area will be different. Each time I stumbled across the way forward, I felt more cheated than elated.

I’d feel relief, certainly. “At last”, I’d think, “I get to play the game I quite like again”. To bounce around enemies like a rabbit gone rampant with an uzi, constant motion the best defence against enemies that don’t know how to deal with strafing. There’s a thrill to hopping round a corner, smushing a fella in a cloak, then spinning round to polish of his friend in one smooth motion. Doing that dozens of times in a row against the same handful of enemies has a way of dulling that thrill, though. It’s like jumping on a rollercoaster and delighting at the first time the operator lets you sit tight for another go. By the time you’ve gone round twice, you know all the twists and turns.

I can’t fault the guns, mind. The shotgun feels particularly chunky, tearing through even the toughest regular enemies with one wee trigger squeeze. It’s a knock-out punch, a boomstick with an oomph you rarely see in modern fare. There’s not a bullet sponge in sight, and the enemies possess a pleasing simplicity. The yellow rubes pack low-key assault rifles, the red ones come close to obliterating you in a single shot. It’s a quick n’ dirty visual language, occasionally overwritten by coloured lights that disguise your enemy’s true potency. A neat trick, if a little overused.

There are drones, spiders and metallic centipede bastards milling around too, plus more varied enemies later on, and I like how they all had me swapping my guns around. (I don’t like that one of those guns is called the penetrator, even if I do have a begrudging respect for the joke buried in that being the only weapon you can dual wield.) The combat’s strengths are undermined, though, when Mr. Old School rears his ugly head and reminds me why modern games don’t let you save in the middle of combat.

If navigation issues were the iceberg that set the ship a-sinking, quick-saves are the dickhead who hogged the lifeboat. I didn’t use them at all, at first. Which led to me getting stuck with a scrap of health, bouncing back and forth between an autosave and a room full of enemies I wasn’t equipped to deal with. After I’d inched my way through that debacle, I couldn’t resist banking every ten seconds of progress. I might have managed to stop, if not for the way those punishing red “cracked-up cyborgs” make frequent quickloads a near necessity. I’d be happy to roll with the punches if they didn’t leave me in tiresome situations.

Ion Fury succeeds at nearly everything it tries to do, but it doesn’t attempt much that I’m interested in. I’d rather not agonise over whether I’m plumbing time into exploring a route that turns out to be a secret, or twiddling with switches whose purpose isn’t immediately obvious. I’ve always found secret hunting more hassle than its worth, and I’d rather not be lost.

It’s a game where old-school decisions too often trump good ones. A blast from a past I never lived through, where puerile humour and “area complete” screens tease you about not being a “real player”. Ion’s tongue might be in its cheek, but I’ve got little interest in what it’s saying.

I’m just so unbearably lost.

I’m getting lost as Cpl. Shelly “Bombshell” Harrison, a cop who spends her days shooting at “cracked-out cyborg punks” daring to rebel against “the longstanding order of permanent martial law”. None of this particularly matters, aside from the way it means I frequently hear her bellow crass nonsense like “nothing that laying down another beating can’t solve”.

Ion’s story, as far as it has one, is told through brief monologues from a maniacal scientist who blew up your house, sometimes rebutted by Harrison’s cack-handed quips. Hardly any of it lands, but that’s almost by the by. This is all set-dressing for the running and gunning – until the set empties, and I’m left wondering where on earth I need to go next.

Getting lost in games sucks at my soul. I’ve spent far too long trundling around Ion Fury’s neon-dusted streets and supervillain bunkers, dipping in and out of rooms like a millennial robbed of Google Maps. Or any kind of map, as I first believed. I didn’t think to comb through the keyboard buttons in search of one, and Ion didn’t think to prompt me to. Or else (if you’ll indulge my suspicions) it deliberately decided against it.

Ion Fury revels in letting you figure stuff out for yourself. It doesn’t just let go of your hand: it jumps into a car and swans off to the south of France with a strange woman you’ve only met once. I’m aware that sounds great, refreshing even, to the eyes and ears of anyone who’s sick of following arrows that tell you exactly where you need to go. But instead of that, Ion Fury challenges observation skills I simply don’t have.

It tries to help me, sometimes. Giant, glowing signs will point me towards progress. Then I’ll follow them into a room with a vent I fail to notice, conclude that they must have been guiding towards a bonus area, and waste twenty minutes in a meandering malaise around the rest of the level. It’s not a rewarding barrier to rub up against. There’s no sense of improvement, no notion that the next area will be different. Each time I stumbled across the way forward, I felt more cheated than elated.

I’d feel relief, certainly. “At last”, I’d think, “I get to play the game I quite like again”. To bounce around enemies like a rabbit gone rampant with an uzi, constant motion the best defence against enemies that don’t know how to deal with strafing. There’s a thrill to hopping round a corner, smushing a fella in a cloak, then spinning round to polish of his friend in one smooth motion. Doing that dozens of times in a row against the same handful of enemies has a way of dulling that thrill, though. It’s like jumping on a rollercoaster and delighting at the first time the operator lets you sit tight for another go. By the time you’ve gone round twice, you know all the twists and turns.

I can’t fault the guns, mind. The shotgun feels particularly chunky, tearing through even the toughest regular enemies with one wee trigger squeeze. It’s a knock-out punch, a boomstick with an oomph you rarely see in modern fare. There’s not a bullet sponge in sight, and the enemies possess a pleasing simplicity. The yellow rubes pack low-key assault rifles, the red ones come close to obliterating you in a single shot. It’s a quick n’ dirty visual language, occasionally overwritten by coloured lights that disguise your enemy’s true potency. A neat trick, if a little overused.

There are drones, spiders and metallic centipede bastards milling around too, plus more varied enemies later on, and I like how they all had me swapping my guns around. (I don’t like that one of those guns is called the penetrator, even if I do have a begrudging respect for the joke buried in that being the only weapon you can dual wield.) The combat’s strengths are undermined, though, when Mr. Old School rears his ugly head and reminds me why modern games don’t let you save in the middle of combat.

If navigation issues were the iceberg that set the ship a-sinking, quick-saves are the dickhead who hogged the lifeboat. I didn’t use them at all, at first. Which led to me getting stuck with a scrap of health, bouncing back and forth between an autosave and a room full of enemies I wasn’t equipped to deal with. After I’d inched my way through that debacle, I couldn’t resist banking every ten seconds of progress. I might have managed to stop, if not for the way those punishing red “cracked-up cyborgs” make frequent quickloads a near necessity. I’d be happy to roll with the punches if they didn’t leave me in tiresome situations.

Ion Fury succeeds at nearly everything it tries to do, but it doesn’t attempt much that I’m interested in. I’d rather not agonise over whether I’m plumbing time into exploring a route that turns out to be a secret, or twiddling with switches whose purpose isn’t immediately obvious. I’ve always found secret hunting more hassle than its worth, and I’d rather not be lost.

It’s a game where old-school decisions too often trump good ones. A blast from a past I never lived through, where puerile humour and “area complete” screens tease you about not being a “real player”. Ion’s tongue might be in its cheek, but I’ve got little interest in what it’s saying.