Chris Crawford is a contradiction: mythologized for his bold vision for the future of games; criticised and dismissed for his lifelong failure to accomplish that bold vision. His numerous critics see him as out of touch and over the hill. A washout. An unrepentant failure. Someone who should give it up and walk away. But he can’t bring himself to do that. He has a dream, and he hasn’t finished laying the groundwork for someone else to carry that dream forward. Crawford is driven by a singular vision — by an idea that he’s pursued doggedly since he left the games industry over 20 years ago. And even now, as I speak to him about Siboot [

official site], his latest attempt to spruik his dream of character-driven interactive storytelling, he remains tormented by a dragon he knows he will never slay.

The famed designer of Atari 800 wargame Eastern Front 1941 and 1985 geopolitical thriller Balance of Power (a game in which your goal was to prevent war from breaking out) left the games industry in 1992 during a speech at the Game Developers’ Conference — the yearly meeting of minds that had begun in his living room five years earlier. In a talk immortalised as The Dragon Speech (you can see it in

five parts on YouTube), he decried the narrowing breadth and growing monotony of commercial games.

He spoke of his dream for games that would express the full breadth of human experience and emotion. And he called for games that combine the interactive immediacy of play with the dramatic punch of a great story — not as separate entities that you swap back and forth but as one and the same. (Then he charged out of the room screaming at a metaphorical dragon that he swore to one day fight for these dreams.)

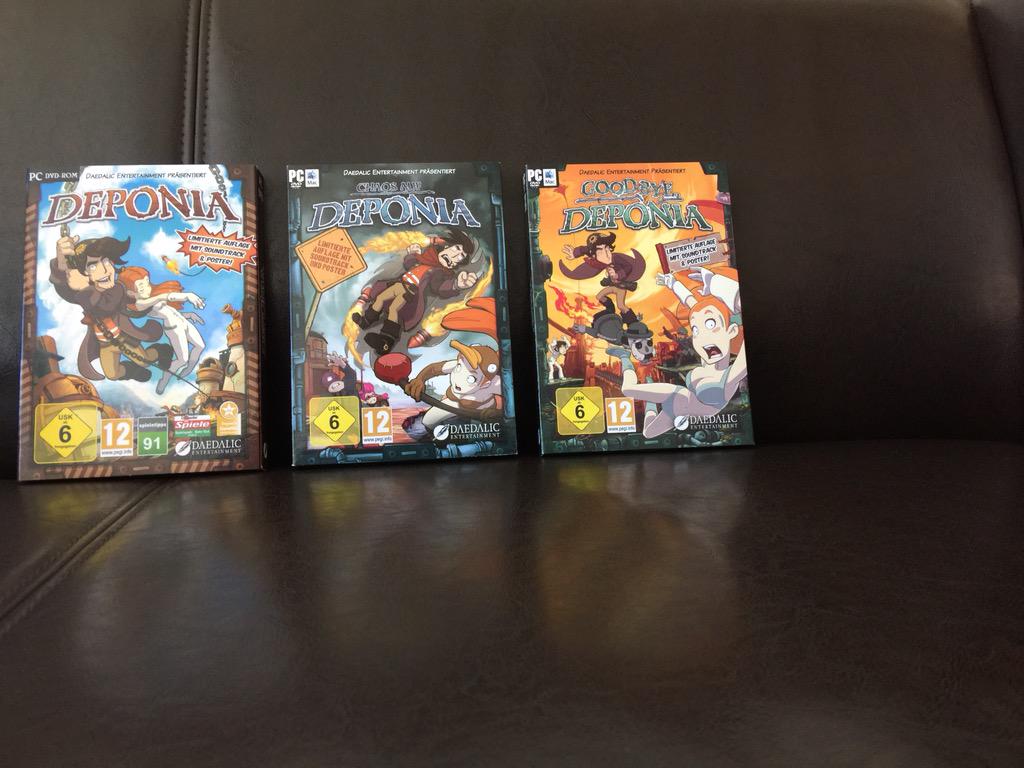

His latest effort at fighting that old foe attempts to rectify the biggest mistakes of Storytron, which was an over-ambitious, overly-complicated unusable mess that even he could scarcely manipulate to his storytelling whims. This new thing is called Siboot, which may sound familiar to the two of you who remember Crawford’s well-reviewed but commercially-disastrous 1987 relationship sim Trust and Betrayal: The Legacy of Siboot. The new Siboot borrows the world and premise of the old one — figure out whom you can trust and whom to betray by judging what they say against what’s visible (or subtly hidden) in their facial expression. But Crawford has rebuilt the whole thing from scratch with a new design that cherry picks the best bits from Storytron and from his decades of research.

“With Siboot I told myself I’m going to strip [Storytron] down,” Crawford says. “Any complexity that isn’t absolutely necessary gets ripped out. I got the balance much better now, with a much simplified system. It is much easier to work with; it’s easier to make design decisions with it. It is much much easier to write the algorithms that control the character behaviour.”

The key to Siboot’s supposed power seems to be that its story is run through algorithms. Its key moments are not written in any traditional sense, but rather designed. Big whoop, you say? There are lots of games in which the story emerges organically according to your decisions and those of your artificial opponents — take Crusader Kings or Civilization, for instance, which both provide complex systems upon which all sorts of interesting decisions can be made. But Crawford argues that these sorts of games don’t count because they “are not very dramatically interesting stories.”

“It might be fascinating to the person who experiences it,” he says, “but ultimately we have to ask does it really approach the quality of what we normally call a story? And the answer with almost all games is, well, no.”

It’s a bold, somewhat dismissive statement that appears at face value to trivialise the achievements of game developers over the past two decades. And it’s likely to immediately get some people on the defensive. But to do so would be missing the point. Crawford doesn’t say this out of malice, and he no longer says it out of ignorance — despite past comments that he’d stopped playing games entirely, he now pays attention to what’s coming out and reads about or watches videos of many new titles (although it’s still rare that he plays something himself).

Games today are incredibly broad and varied. They tackle themes such as poverty, depression, love, war, duty, regret, longing, and death in myriad ways. “The indies,” Crawford says, “are the best thing that have happened to this industry in a long, long time.” The proliferation of cheaper, better tools and more efficient distribution systems has brought with it an explosion in creativity in terms of both development and criticism of games. It’s brilliant, he agrees, and many fascinating ideas have come out of it. But for Crawford it’s not enough.

“The types of changes that I am observing are really fine improvements on fundamentally ancient architectures,” he says. “I can respect the way they took this classic architecture and rendered it for modern technology and modern capabilities, but deep down inside it’s still the classic design. That doesn’t make it bad. Shakespeare is still good today, even if Hamlet is using a machine gun instead of a sword.”

Crawford feels there is something very specific yet vitally important that remains absent from videogames past and present — something that he believes would bring with it a paradigm shift in game design. To explain, he turns to a concept from psychology: mental modules. It’s a theory that suggests there are innate functional structures in the human brain dedicated to different processes.

“There are a lot of different ways of slicing the pie up,” Crawford says. “But five of the most important modules are motor module for musculature [think reflexes and dexterity], visual-spatial for navigation and recognising 3D worlds, cause and effect — our knowledge of realistic things. If you drop something, it falls down. If you put your finger in a fire it burns your finger. Those types of relationships. Those are the three types of modules that games most commonly challenge.”

Games rarely challenge the two modules that Crawford is aiming for with his interactive storytelling. These are language and social intelligence. He argues that the latter is what other forms of entertainment are based on. “You don’t jump around in your seat in the movies,” he says. “They don’t train visual-spatial — in the movies people don’t spend a lot of time navigating their way through mazes. They just say I’ll go there and the next shot is them there, not traversing it.”

Movies and games are different, of course. They have different strengths. Movies show you people making big, life-altering dramatic choices. Games let you make innocuous, inconsequential choices, interspersed from time to time with meaningful ones. Movies are driven by relationships; games are driven by you, the player.

We as an industry tend to celebrate that about games. We revel in the little things and the freedoms that games give us. But Crawford wants a game where there is neither an open world to live and explore in nor a path laid out before you. He wants something that provides the narrative focus of a good novel or film coupled with the agency of a game, without any pre-authored story branches and with complex characters who interact with one another independently of you but who each have a definite role to play (like an antagonist or mentor).

I suggest that an MMO such as EVE Online might challenge your social intelligence and be filled with interactions that could each potentially be dramatically significant, but he waves it away as too unfocused. “There’s no such thing as a supporting character in a multiplayer game,” he says. “Everyone wants to be the protagonist. In interactive storytelling you create artificial characters who you deliberately establish as supporting characters, primary opponents, antagonists, and so forth.” Crawford wants an artificial agent — an algorithm — to be pulling the strings behind the scenes.

His second-in-command on Siboot, art lead Alvaro Gonzalez, explains that an MMO is akin to a social intelligence sandbox whereas Siboot is meant to be a forerunner to a “dramatic sandbox where the most important thing is to have control of the story, even though the player has total freedom on how that story develops.”

Gonzalez explains further with an example of how this model of interactive storytelling might be applied to role-playing games: “At the moment, a lot of RPGs don’t have meaningful quests,” he says. “Like *booming voice* ‘you have to kill 40 pigs to get 1000 tails to take it to’ — that’s not meaningful because the player doesn’t have to use any module to get that quest. It was easy. But if the player has to make meaningful decisions using this social intelligence while they approach these NPCs, then that quest is going to become very important and very meaningful, and that will breed dramatics.”

Essentially, if I understand him correctly, RPG quests would become meaningful because there’d be fewer of them, their goals would involve an intrinsic motivation on the player’s part, and they’d take a whole lot of talking, conversational probing, and emotional investment to get in the first place.

What it really comes down to is that, in Crawford’s vision of an interactive story, your every choice could change the course of the narrative. Branching paths aren’t written so much as generated, at every turn altering the story to optimise the dramatic punch lying ahead.

Siboot is meant to prove the concept and kickstart a revolution in game design. Seen at face value, it doesn’t seem so different. Its claims of complex characters and symbolic language (with 40 to 50 verbs and several degrees of nuance) aren’t perhaps as unique as Crawford makes out, and more cinematically-minded games are already starting to weave in more subtle facial animations that you have to consider as you make your decisions (although Crawford plans to go further by having the micro-expressions be algorithmically varied according to multiple inputs rather than hardcoded from motion capture).

In fairness, Crawford is quick to admit that Siboot is painfully constrained in terms of this grand vision of character-driven, algorithmically-defined, social intelligence-focused interactive storytelling. “I’m sure many people will look at that and once they understand how it works they’ll say, ‘I can do better,'” he reasons. “That’s the whole point and purpose of this project.”

Siboot is

on Kickstarter right now. It doesn’t appear that it’ll reach its goal, but it will be finished and released regardless — to be followed some time later by open source code for both the game and its underlying engine, the StoryWorld Authoring Tool. “I’m no longer interested in the money or the fame,” Crawford says. “I’m not rich but I’ve got enough money to be comfortable, so I don’t see any need to commercialise this project. The Kickstarter is really to raise money for the team members; it’s not for me.”

Siboot, meanwhile, is really to inspire developers to tackle storytelling from a new angle, to give academics something to play with in their interactive storytelling research (he’s actually been asked to keynote the next International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling), and to prove that Crawford hasn’t been barking up the wrong tree all this time.

Then, he says, “I can retire with the sense that my life was not a waste.” And maybe someone else will finally slay that dragon, stopping for just a moment afterwards to pay respect to Crawford’s failed attempts.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)