We used the same conversation editor for both games. The tool is really part of a stand-alone tool

set called OEI Tools. It has been developed in-house by our excellent tools team over the past 11 years (IIRC). I believe development on the tool started on our Aliens project (RIP). After working with a few different dialogue editors, including the tree-based editor we used for Neverwinter Nights 2, I was convinced that an editor with a flowchart like Visio (which I had used to set up character state machines for another game) would be an improvement.

Several designers did not like this idea at first glance because the tree-style layout was perfectly adequate for 75% of our dialogues. It was the 25% that got really large and complex that became hard to navigate. To make a long story short, we iterated on the editor while working on Aliens, Dungeon Siege III, South Park: The Stick of Truth, and Stormlands (RIP).

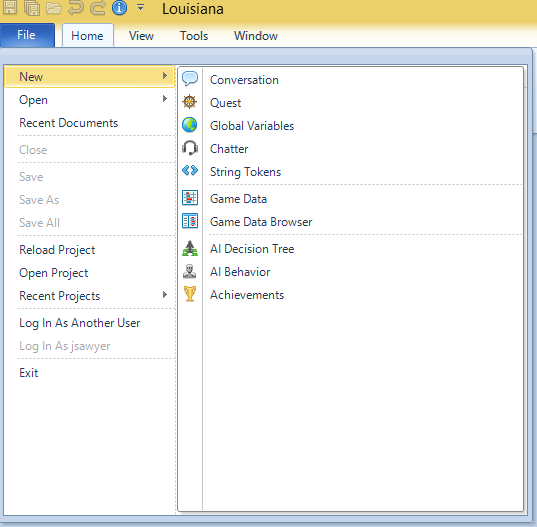

By the time we got to making Pillars of Eternity, the toolset had improved immensely. Over the course of Pillars and Deadfire, the tools team added a huge amount of functionality. We now use the tool for writing dialogue and chatter, setting up quests, maintaining our global variables, building AI behavior trees, and editing all of our game data (character classes, races, abilities, etc.).

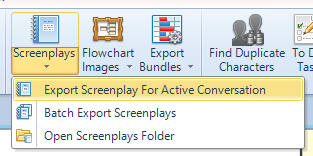

It is integrated into Perforce (what we use for source control) and our string database. We maintain our entire localization pipeline through the tool and are able to export conversations to xml/json, voice actor scripts, screenplay-style scripts, and even to pdfs that maintain the flowchart structure. It is by far the best dialogue tool I’ve worked with and our tools team deserves massive credit for it.

Here are a few shots. Warning: some Deadfire spoilers follow.

Obsidian is always working on multiple projects concurrently. Some designers also split their time between projects. Switching projects is relatively fast and painless. It connects to the database and reloads all of the project-specific data and plug-ins.

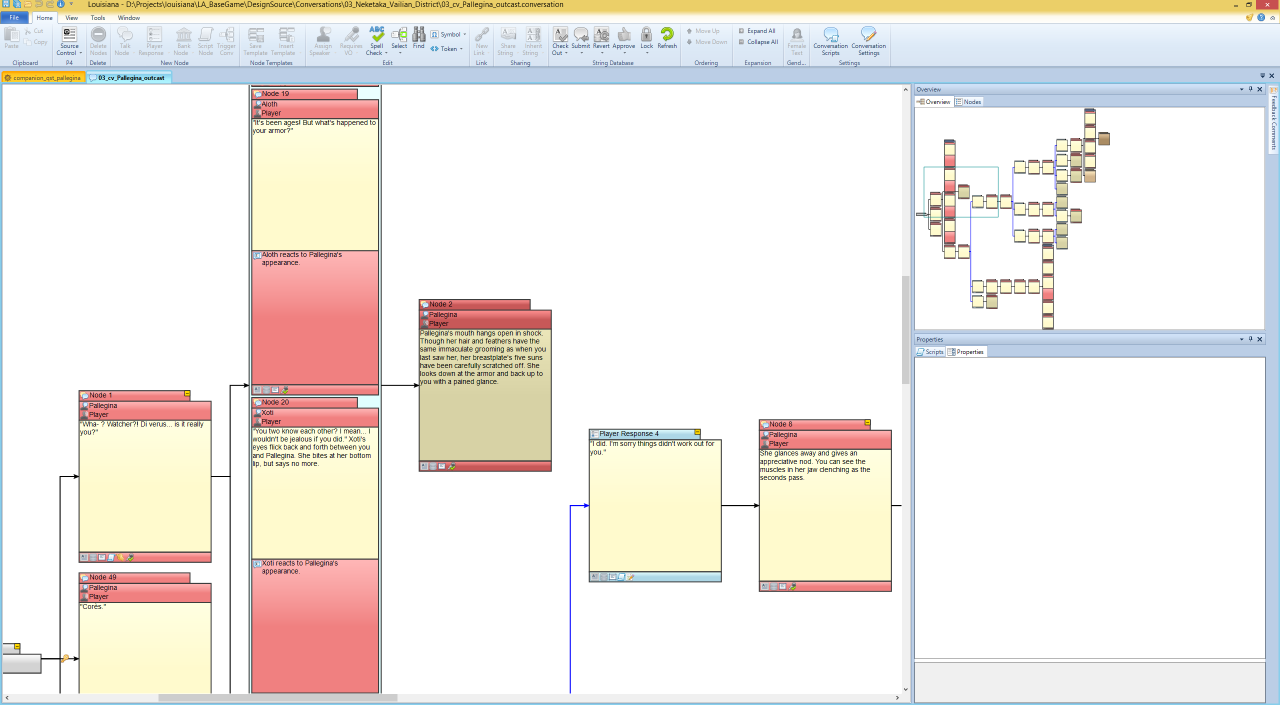

I’ve posted many screenshots of our editor before, but here are some different types of conversations for contrast.

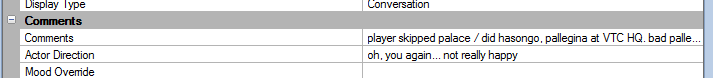

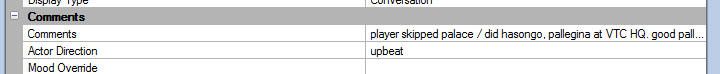

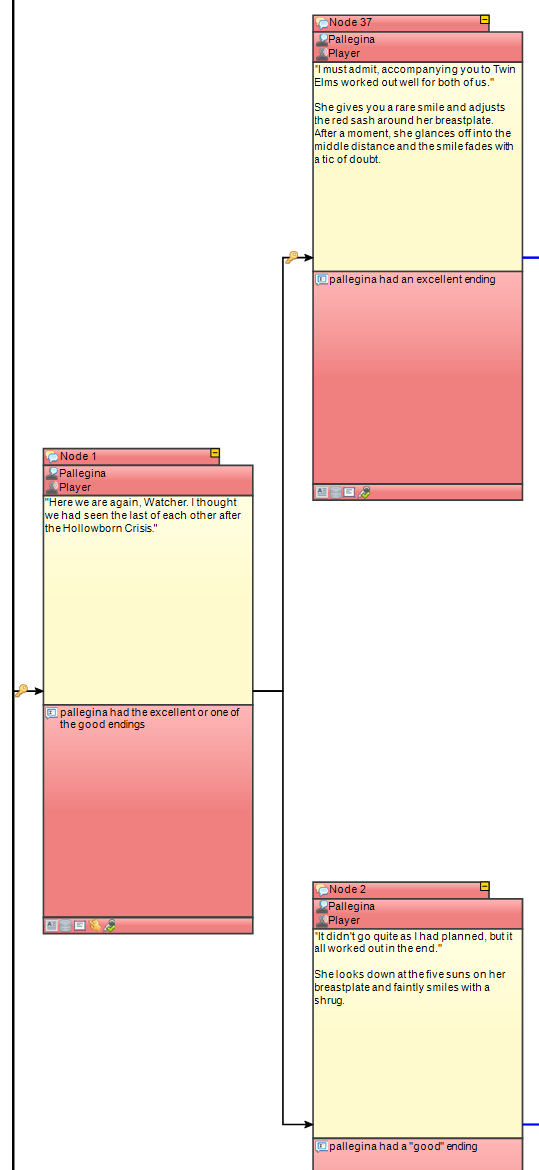

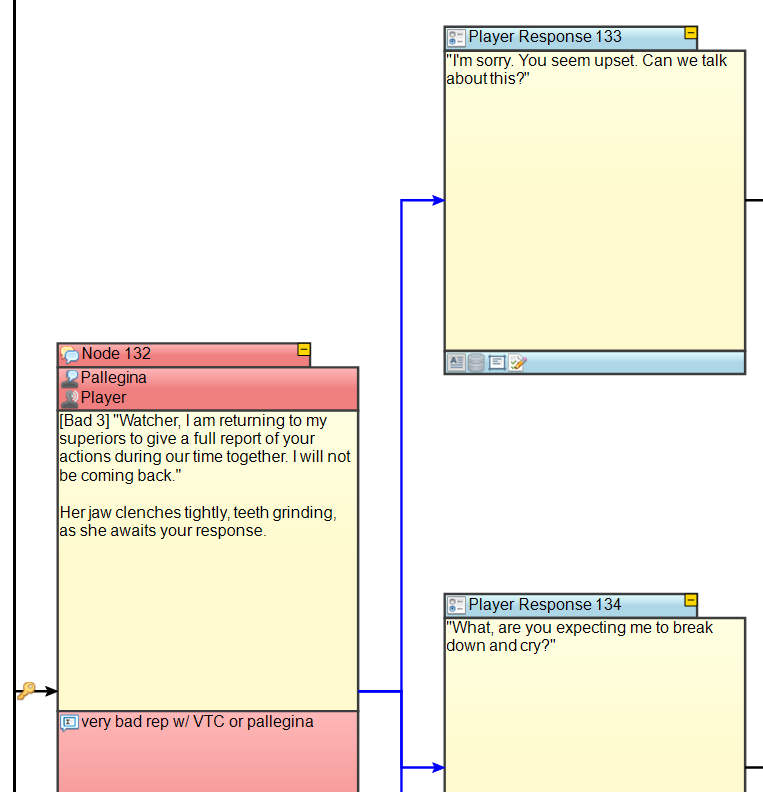

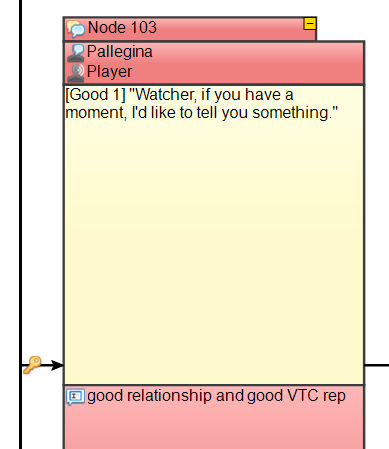

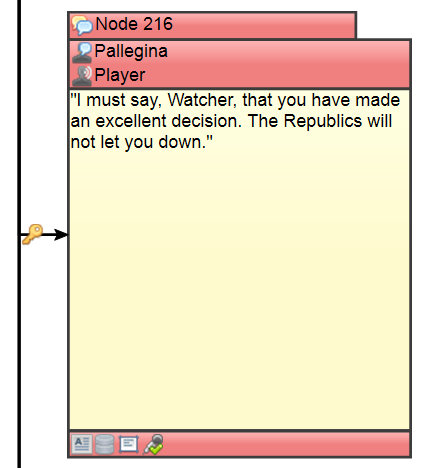

This is Pallegina’s “outcast” conversation if she was banished from the Vailian Republics (and not redeemed) at the end of Pillars of Eternity. The flowchart is relatively simple. The tall stacks are “Cascade Nodes”. All companions who have lines written and inserted in the Cascade Node will speak up when the node is hit. This differs from a Bank Node, where generally a single character will respond, either at random or based on node order. These distinctive shapes become navigation aids in larger conversations.

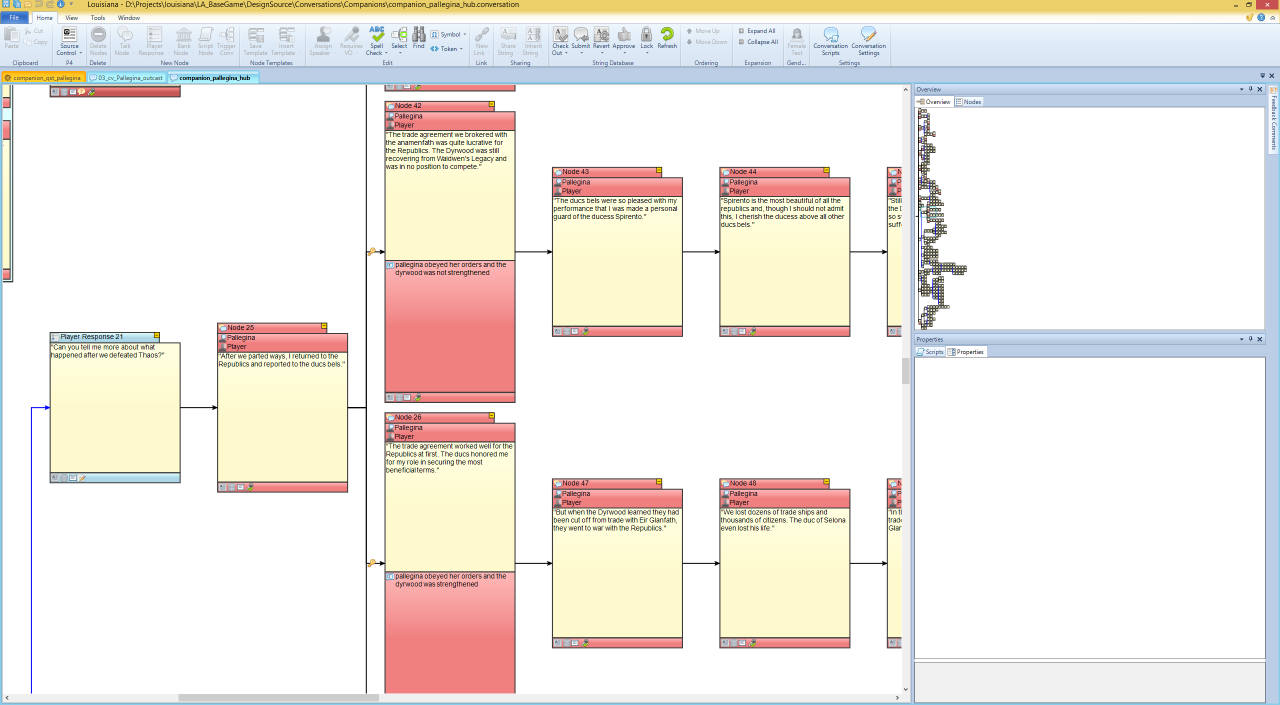

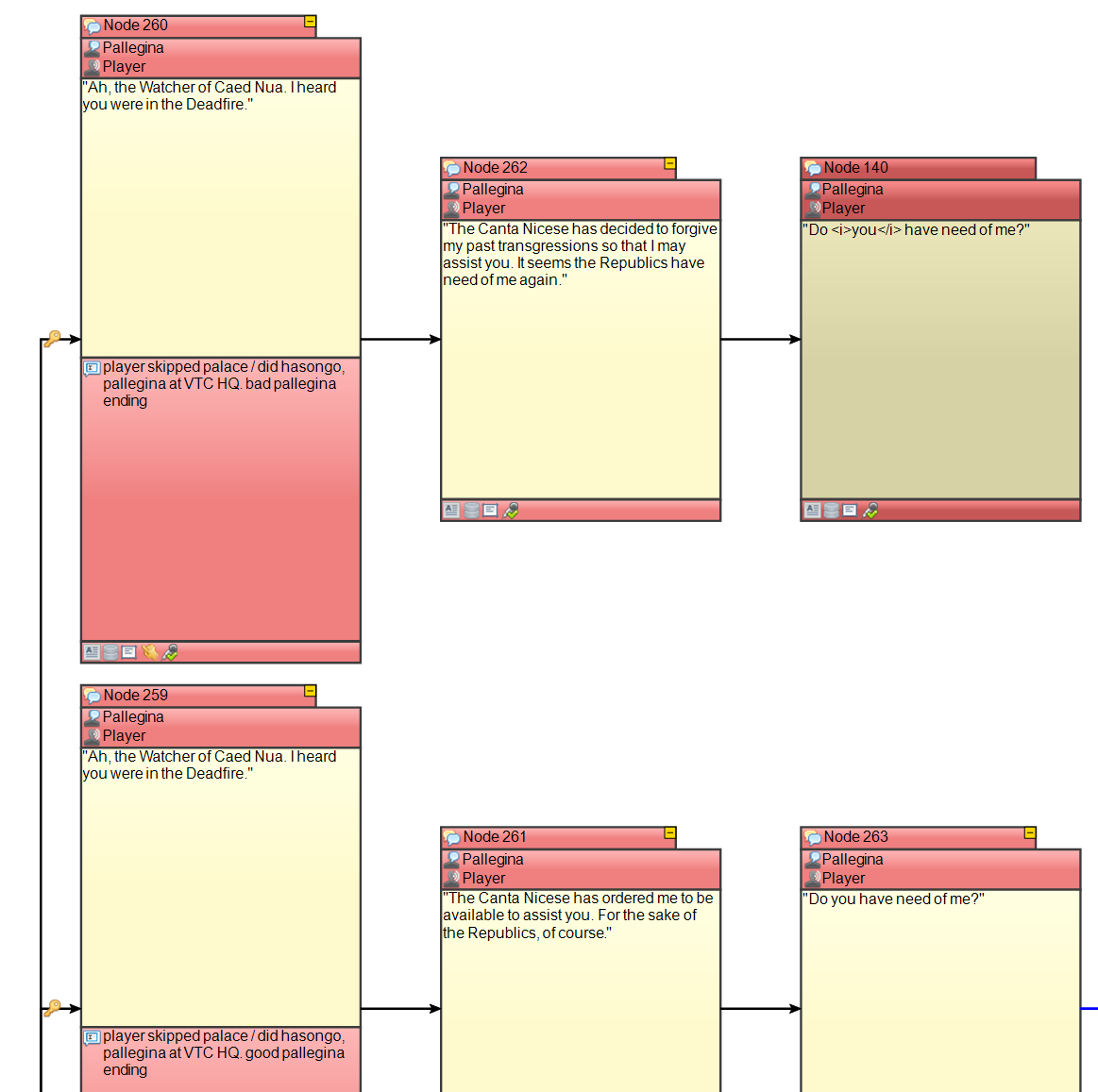

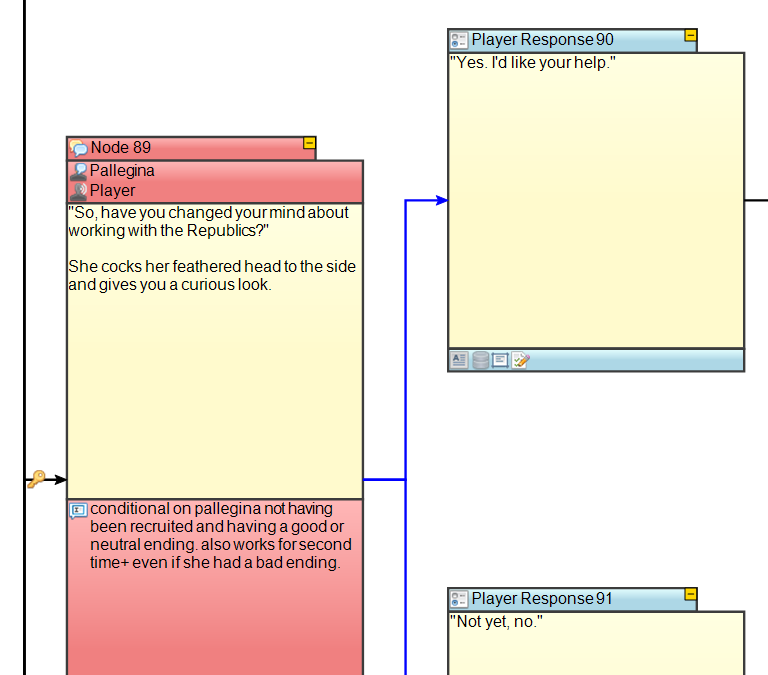

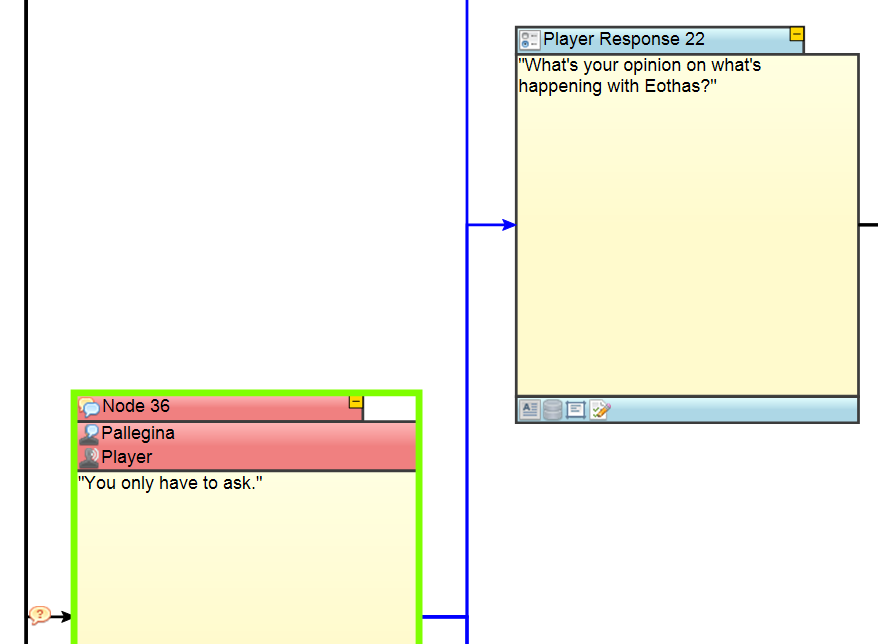

This is Pallegina’s hub conversation. As you can see from the density of nodes in the Overview window and how “tall” the stack is, hubs usually have a lot of entry points. This is because hubs often have to handle myriad conditions for starting conversations with a companion over the course of the entire game. I’m going to go a little more in-depth with how many of these there can be.

These are all in vertical order from top to bottom, which is the order in which the game processes nodes. Any node with a key in front of it has conditionals. If the conditionals are not met, it drops to the next node below it. This process continues until it finds a valid node.

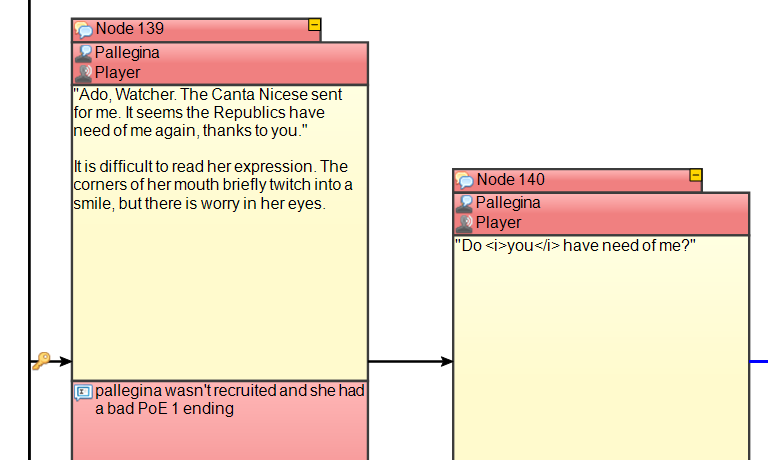

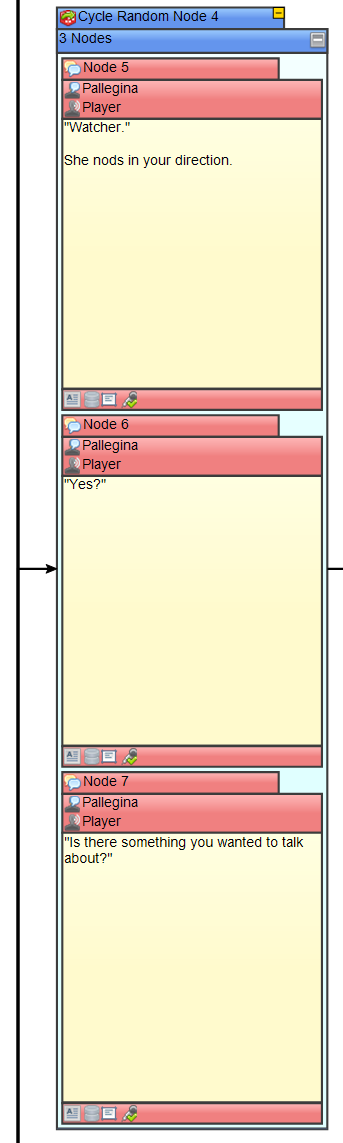

Two slightly different circumstances lead to different introduction nodes with different reads:

In this pair, there is a “generally good” intro node that bifurcates into “excellent” and “good”.

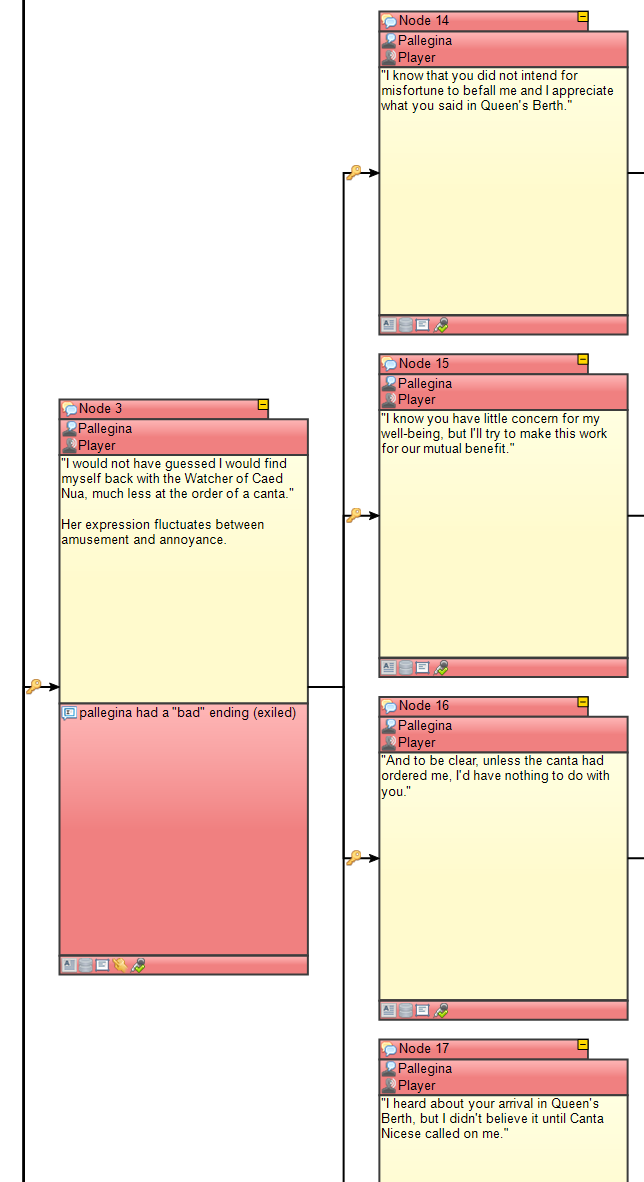

“Bad” ending intro that gates based on how the player treated Pallegina at Queen’s Berth. If the player didn’t speak to Pallegina in Queen’s Berth, it falls through to the bottom option. Again, these are all

introduction nodes. The hub has to deal with a lot more conditions.

This is typically launched by the game based on conditions in the Companion Manager, but can also appear if the player forces conversation with Pallegina while the same conditions are met.

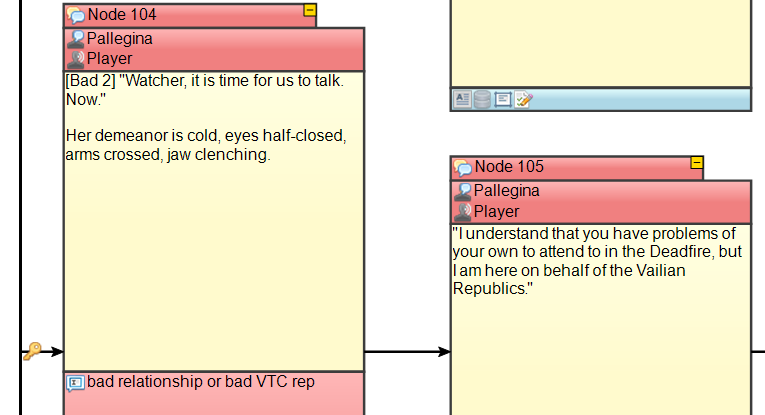

If the Bad 3 is not hit, it falls through and checks for Bad 2.

Bad 1 and Neutral do not have nodes. Those reputation values are tracked, but Pallegina doesn’t respond to them. If the player doesn’t have a Bad 3 or Bad 2 rep with Pallegina, it falls through to Good 1.

If none of those reputation conditions are true, it falls through to her general question node with randomized initial nodes. It always loops back to:

With Player Responses that are conditionalized.

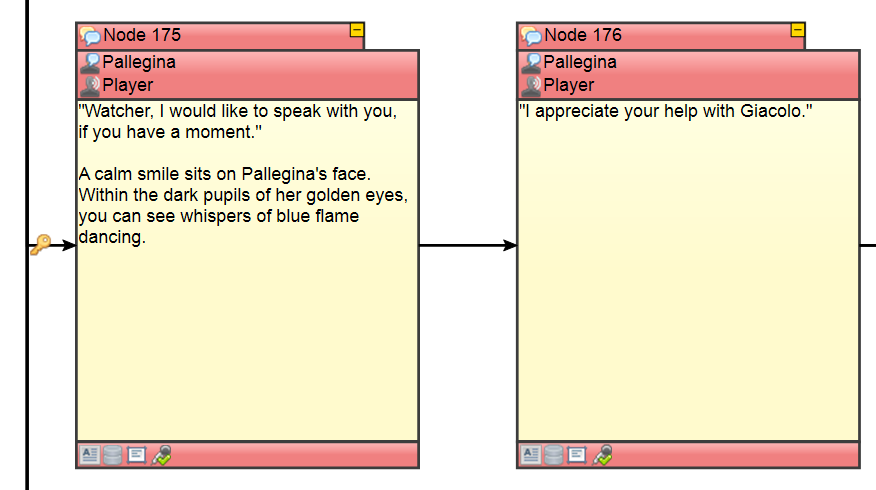

For after you do Pallegina’s personal quest.

A one-off line that fires when the player allies with the Vailian Trading Company.

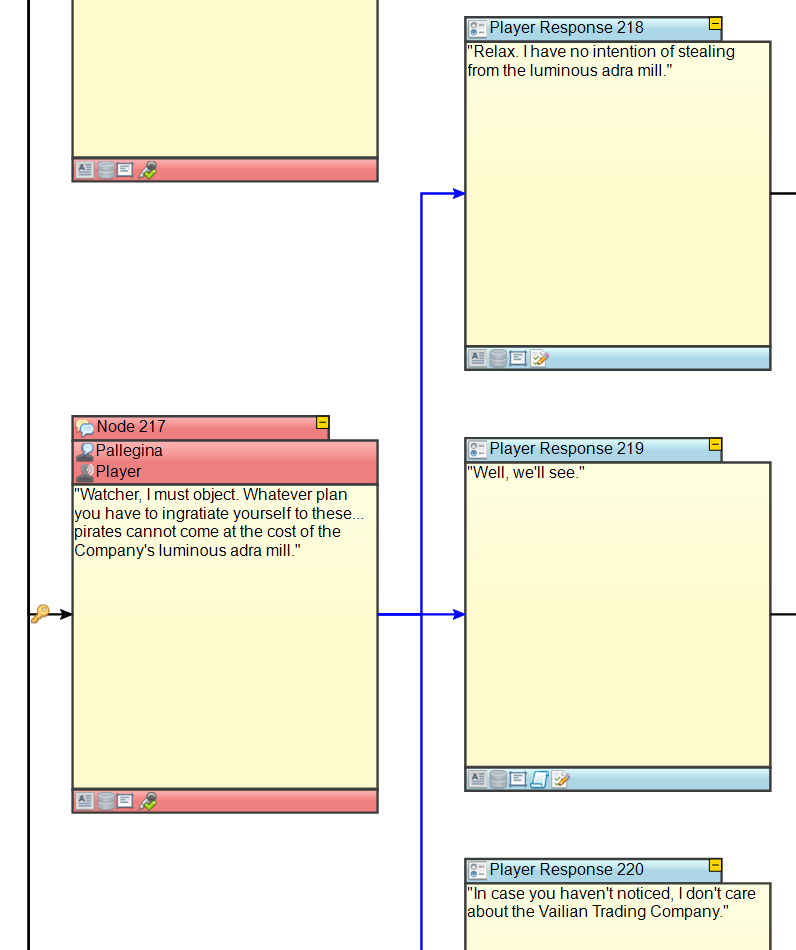

In the Undercroft, Mad Morena tries to get the player to rob the luminous adra mill. It seemed weird for Pallegina to interject in the middle of a pirate fort, so she has a hub branch that fires for that special occasion.

She really doesn’t like it if you ally with another faction, so she has a general, “The buck stops here” hub branch that gates based on your allegiance.

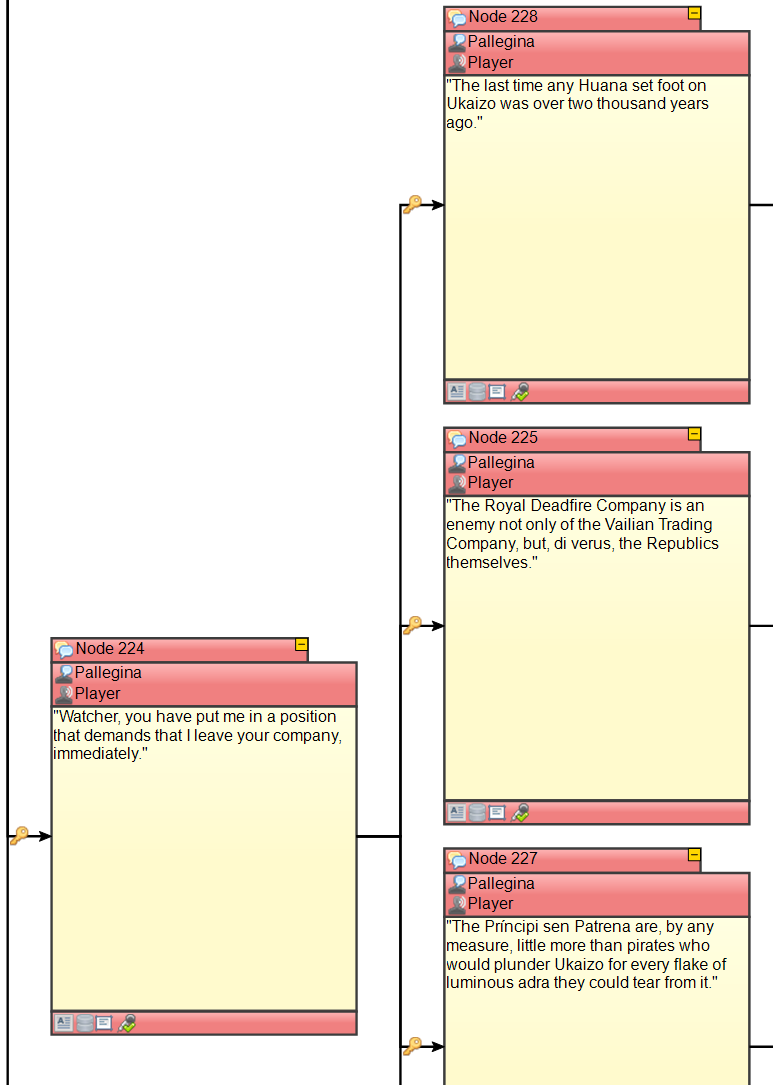

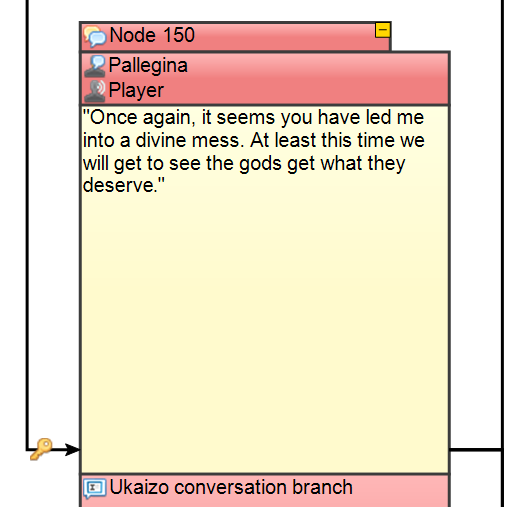

End of the game. You might be saying, “Hey, Josh, a bunch of these conditionalized branches are lower than the unconditionalized question branch.” You’re right. And technically they don’t need conditions because it should always fall through to the question branch (stopping). But I still conditionalize them just in case I need to shift their order (which is mercifully easy).

Those nodes below the question node are typically called by scripts, so they should

not be hit if the player just randomly starts dialogue with Pallegina. The script will say, “start conversation companion_pallegina_hub at Node 150.”

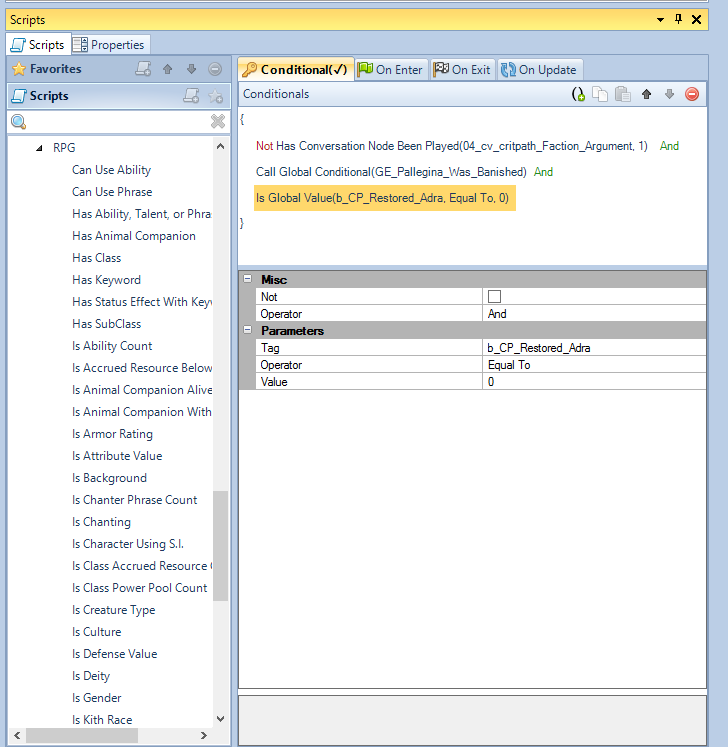

And here is what our script window looks like:

Scripts on a node can be conditionals (i.e., requirements to display or play the node at all) or they can be events that fire when the node is entered (On Enter), exited (On Exit), or updated via other means (On Update). When you’re in one plane, the scripts pane only displays the appropriate types of scripts. E.g. Has SubClass is only appropriate in Conditional, not On Enter, et al.

The Call Global Conditional is an

incredibly useful function for us. It allows designers to bundle together a set of conditions elsewhere and then check the whole group of them through one reference. Pallegina can be banished in a number of ways in Pillars 1, i.e. through different conditions. The Call Global Conditional GE_Pallegina_Was_Banished goes through them all and returns True or False. It’s much easier and cleaner than checking the whole set every time.

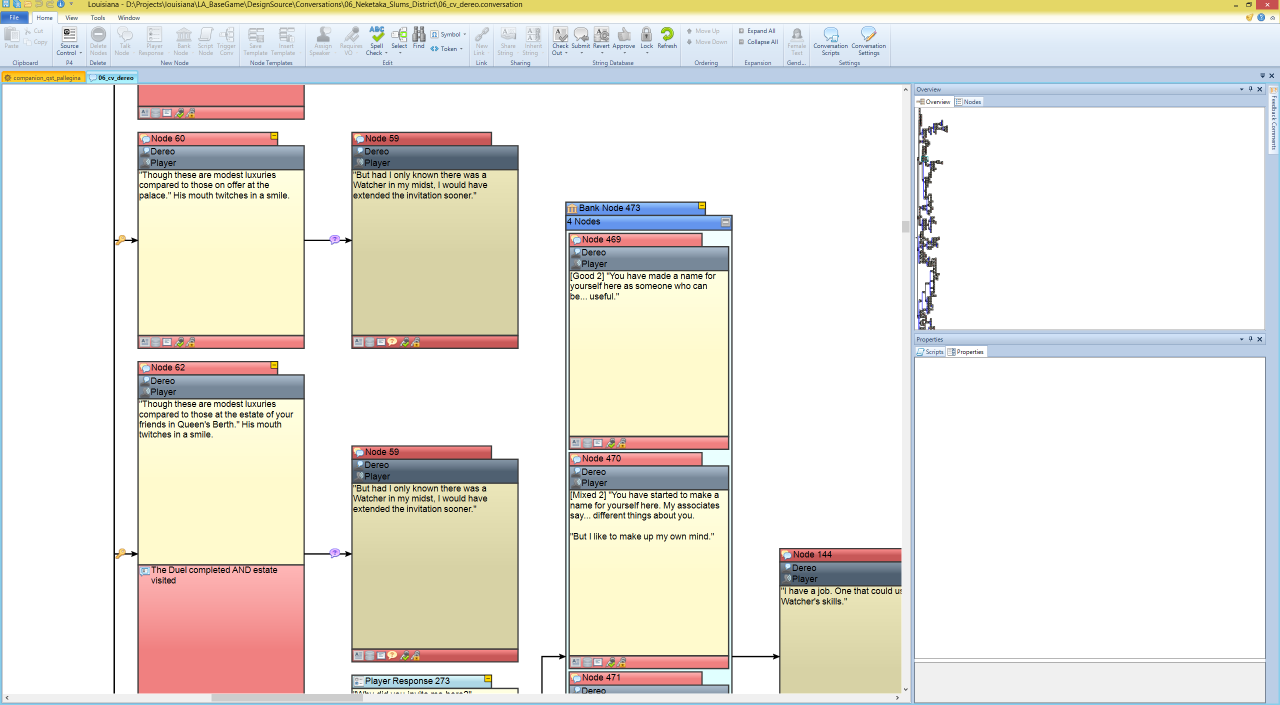

Now for some more contrast: Dereo the Lean:

Dereo’s conversation was sort of a nightmare because he’s technically involved in three (IIRC) quests. Because of all his starting states, Carrie Patel (his writer) had to construct a lot of different entry points for him.

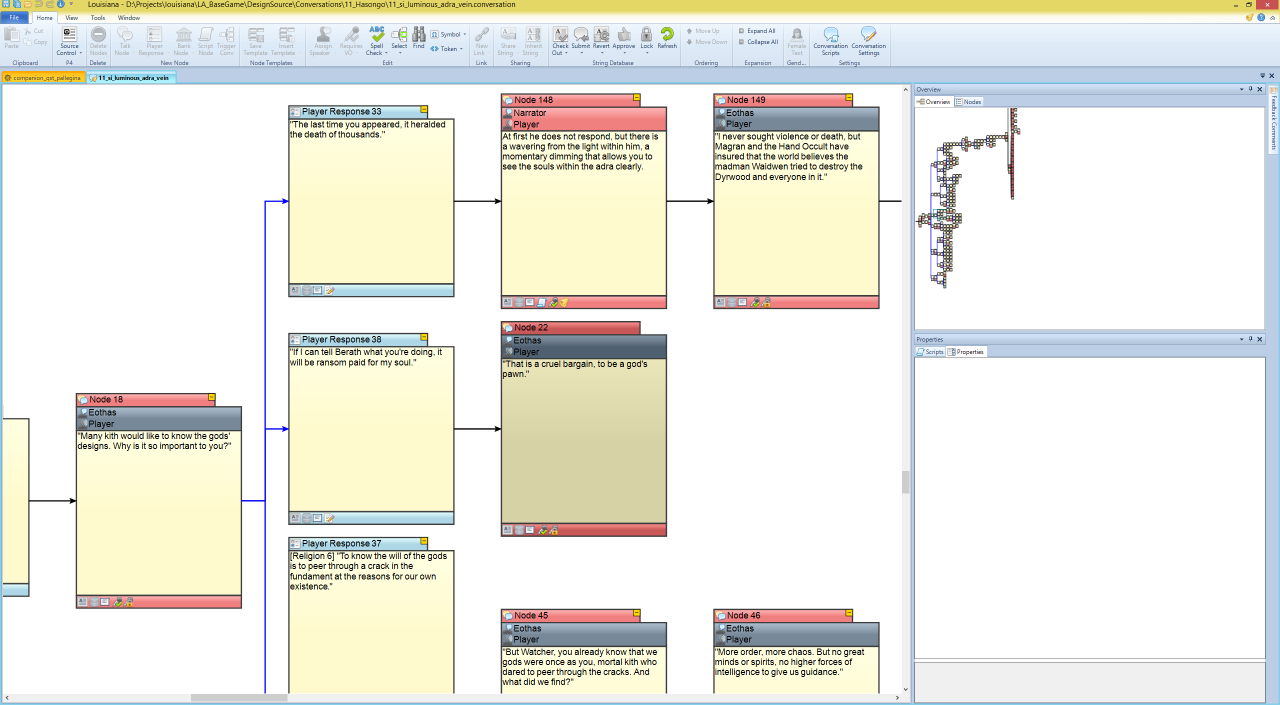

And here’s your conversation with Eothas at Hasongo:

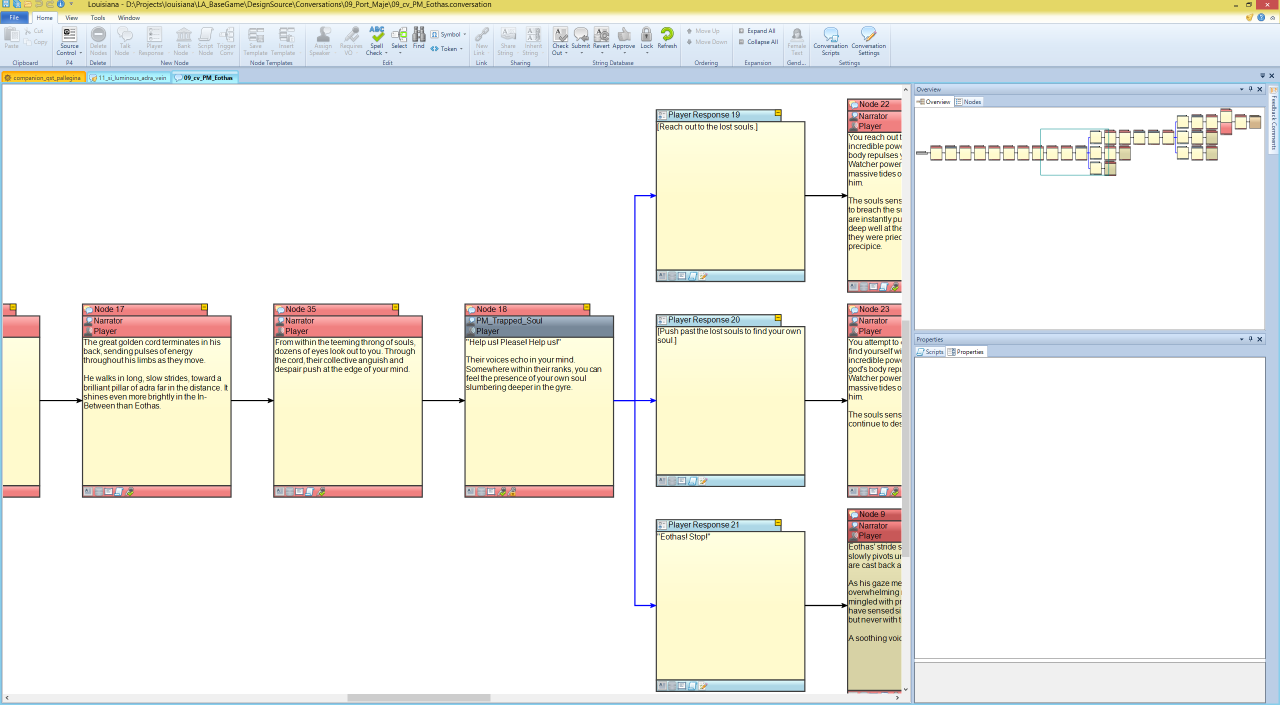

Critical path story conversations tend to have more “forward thrust”. They extend farther horizontally because they’re pushing a topic forward. Cf. with the first Eothas conversation at Maje Island which has much less player input:

The player is essentially witnessing something happening and only has two interaction points.

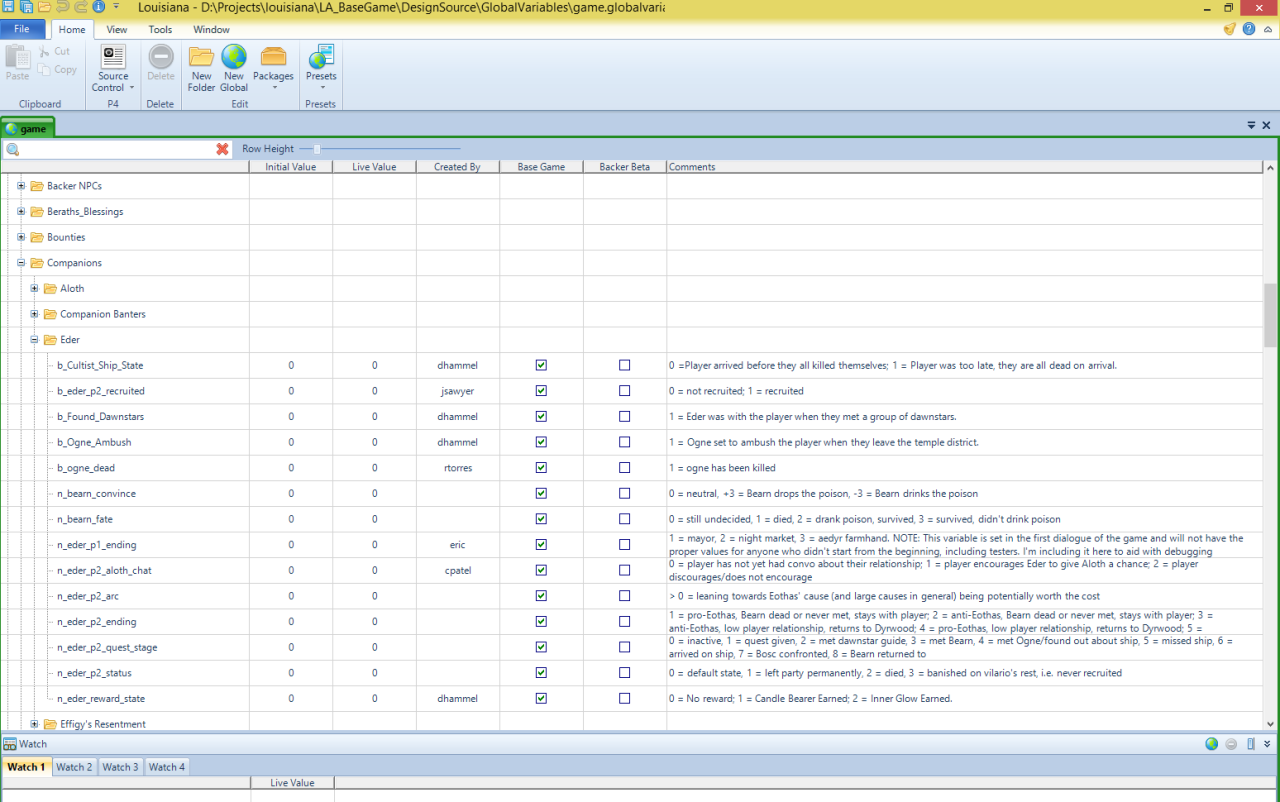

Enough about the conversation editor itself. Here’s the global variable editor:

We set up all of our global variables in this data bundle. The editor also has the ability to interface directly with the live game so we can see where variables are at any given moment.

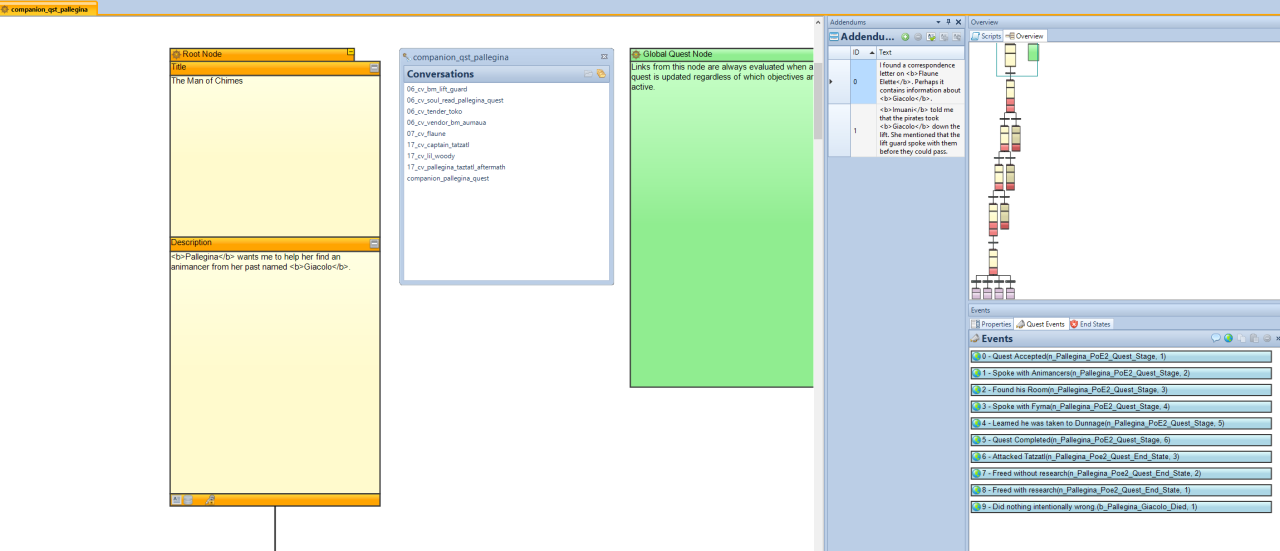

Our quest editor is similar to the conversation editor, but has a vertical structure. More complex quests branch more. This one is Pallegina’s. The Conversations window allows the quest designer to link all quest-relevant conversations to quest data. In turn, this allows our narrative designers to quickly move through every conversation in a quest for a writing and/or review pass.

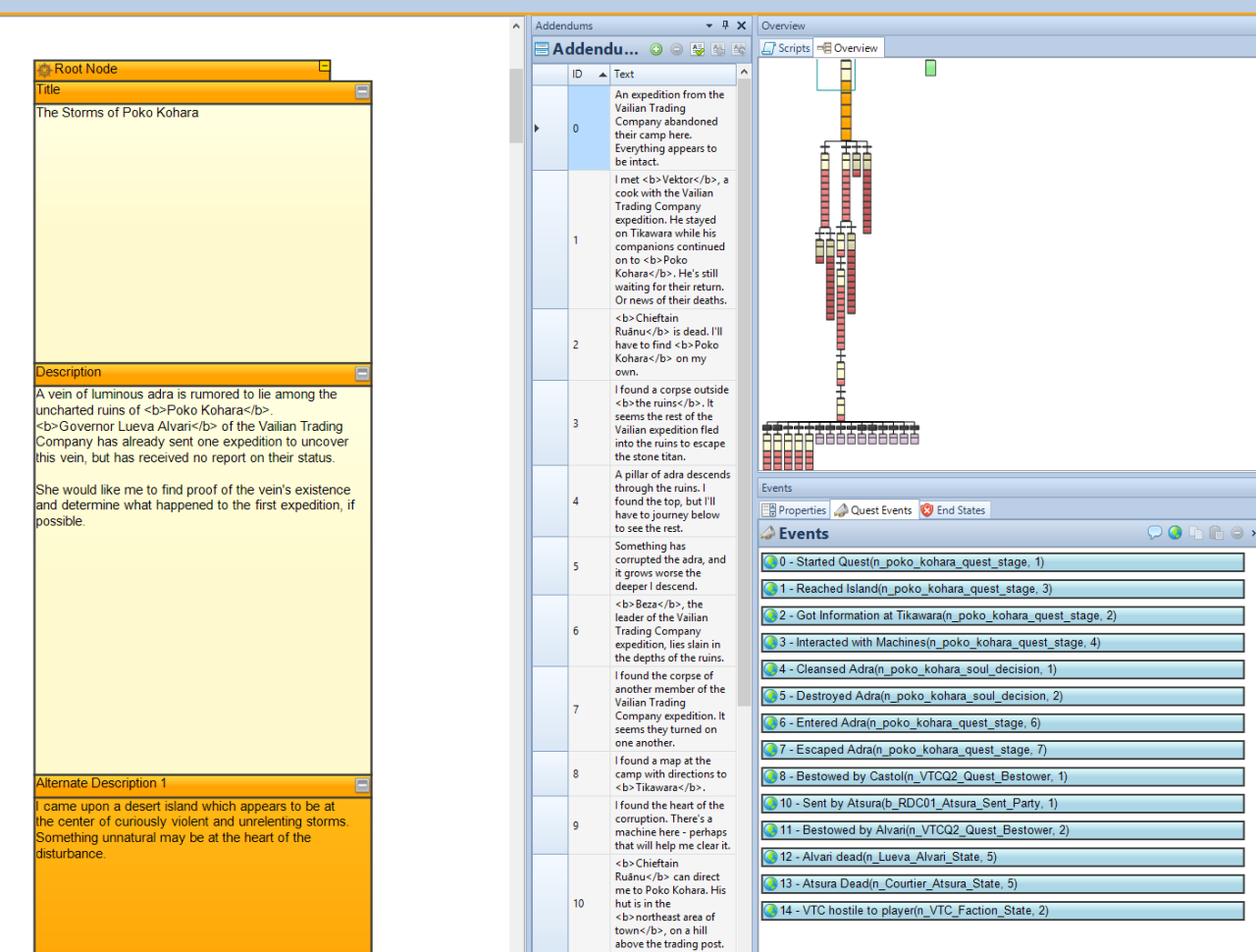

For comparison, this is Storms of Poko Kohara, a much more complicated quest that itself has two potential “wrapper” quests from the VTC and RDC:

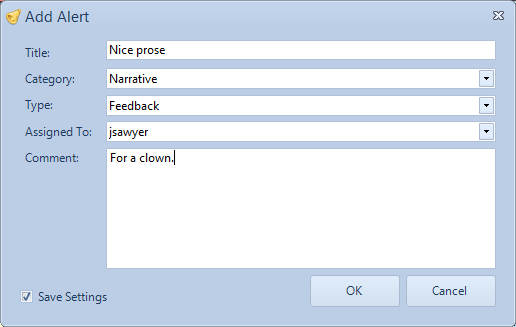

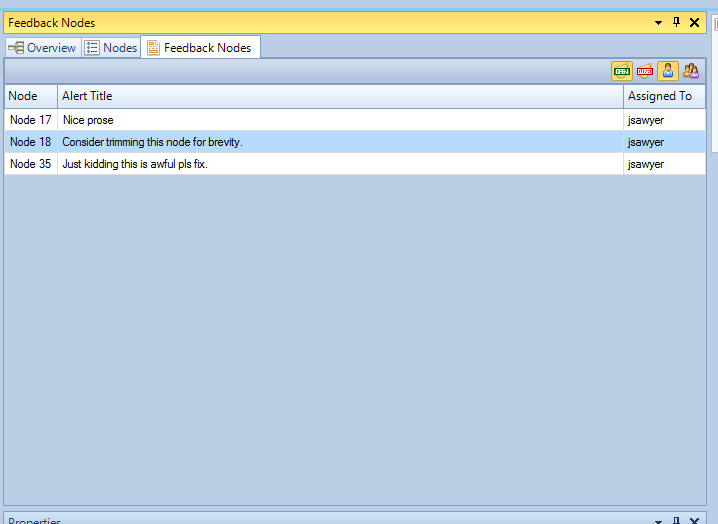

A new feature for Deadfire is the alert system. Alerts can be used by devs to give feedback or request action on an individual node. Here I’m leaving feedback for myself:

These then go into a Feedback list that the author can quickly go through (it pulls you to the correct node) and either ignore or mark as Resolved.

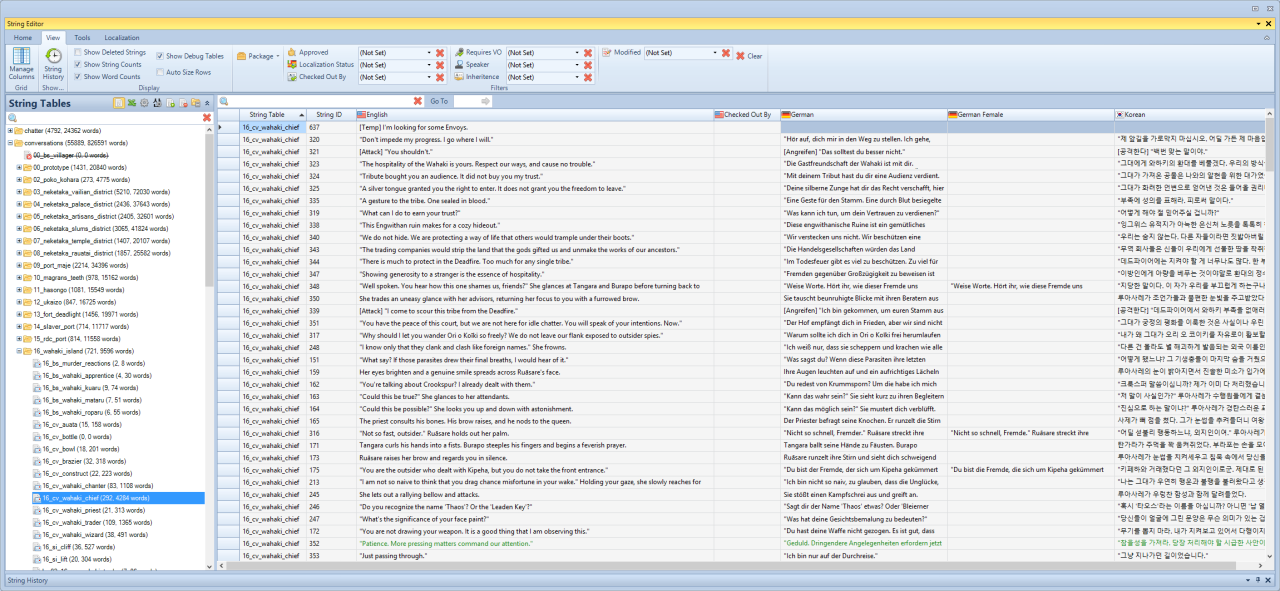

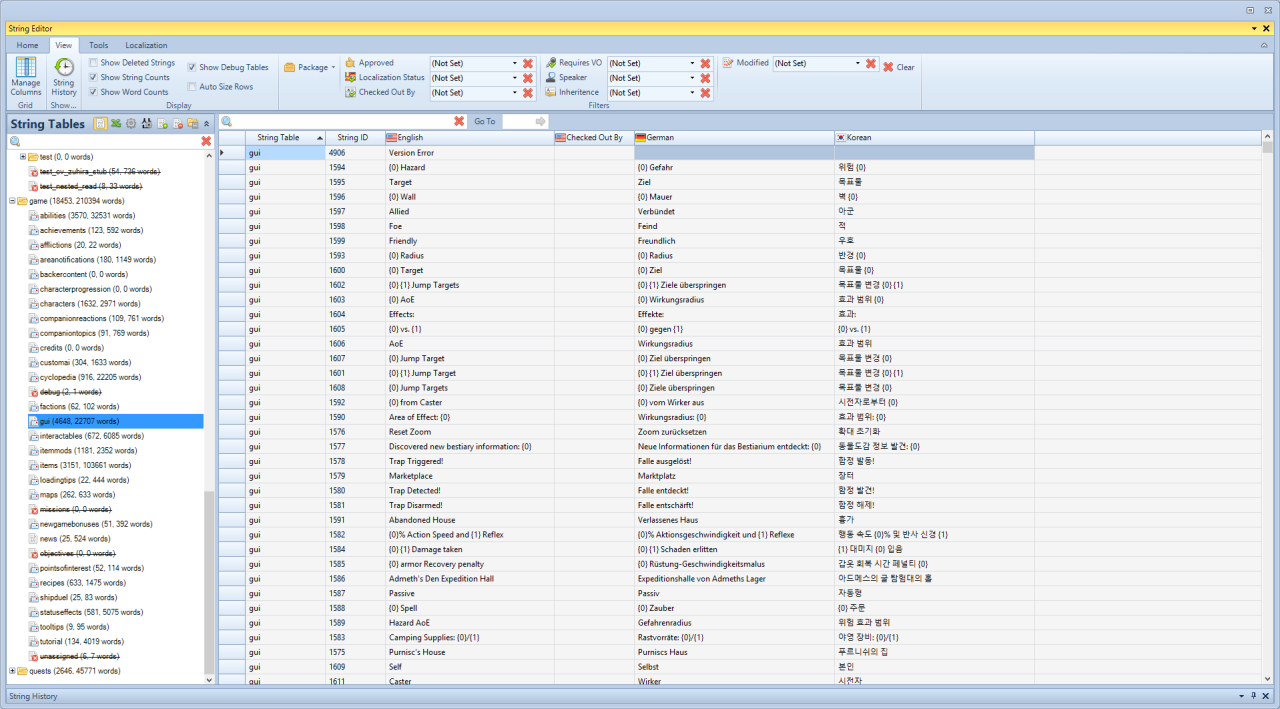

And finally, a vital element of any dialogue tool: the string database.

The database is broken into individual tables that contain each conversation as well as each group of similar gameplay strings (e.g. “GUI” and “Cyclopedia”).

The column view is customizable. In the second window, I removed German Female because GUI strings don’t often need a female-specific translation auf Deutsch.

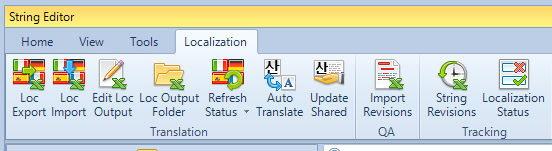

We have a robust pipeline for handling localization, from generating files for translators to re-importing them. And, of course, tracking progress.

We also have a lot of other incredibly useful functionality, such as the ability to export screenplays for actors and flowcharts for visual reference when someone doesn’t have the toolset installed.

As I’ve said before, this is an excellent toolset and it’s a testament to the passion and attention to detail of Obsidian’s designers and tools programmers. This particular toolset is very well-suited to the type of games we make. Most studios will never need many of these features, but I do want to say to the developers out there that investing in tools can pay enormous dividends. If you don’t have the time or money to make your own tools, look into third party options! They exist!

And if you do have the time and resources to make your own tools, feel free to steal (or ignore) ideas from companies that have already put in the work.

Thanks for reading.