The writing in the game is a touch weaker than its visuals; scriptwriter Dave Cummins isn’t incompetent by any means, but nor is he another Alan Moore. As tends to happen constantly in the adventure genre, the overarching “dark, serious” plot gets immediately overrun in the details by a collapse into comedy, a genre which seems far better suited to the outlandish puzzles that are the driving force of most adventure games, this one included.

Still, the blow of this failure of the game to stick to its dramatic guns is eased immensely simply because a lot of the humor is really, truly funny; it never feels forced, something which is by no means the case in all or even most of this game’s competitors. This is wry British humor at its best: it’s sneakily smart, and also a bit more deviously risque than what you might find in a contemporary American game of this ilk. (One running gag, for example, has to do with a skeezy character’s collection of “pussy pictures” — which, yes, turns out just to be pictures of cats.) You begin the game with a sidekick already in your inventory: your childhood friend Joey, a synthetic personality on a circuit board who can be transplanted into various robots as you go along. His sarcastic banter is a great source of fun and oblique hints, such that when he’s not with you in some sort of embodied form you genuinely miss him. In fact, I’d like the game even more if it had more of him in it. He’s prevented from joining the absolute highest ranks of classic adventure-game sidekicks only by the fact that he’s onscreen less than half the time.

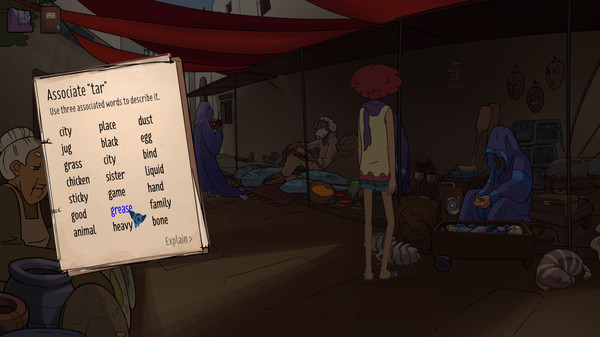

If you hate convoluted adventure-game puzzles on principle, the ones here will do nothing to convince you otherwise. If you enjoy them, on the other hand,

Beneath a Steel Sky is a solid implementation of their ilk. It’s not a particularly easy game, but nor is it an unusually hard one for its time, and it is consistently logical in its silly adventure-game way. (In this sense as in several others, it stood head and shoulders above

its few competitors among homegrown British graphic adventures, whose grasp on the fundamentals of good game design tended to be shaky at best.) It eschews the contemporaneous interactive-movie trend, with its chapter breaks and extended cut scenes, for a more old-school non-linear approach; for the bulk of the game, you have a fairly large area to roam and multiple problems to work on. There’s never a sense that the puzzles were hasty additions inserted just to give the player something to do; they’re part and parcel of a holistic experience.

Vestiges of Revolution’s earlier rhetoric about creating more dynamic worlds do remain here. Characters are still a bit more active than you might find in a Sierra or LucasArts game, and an unusual number of the puzzles rely on analyzing their movements and timing your own actions just right. That said, the most frustrating aspects of

Lure of the Temptress have been excised. For the most part, the designers opted to return to the things that were known to work in this genre rather than continuing to blaze problematic new trails — and it must be said that the game is all the better for it for their conservatism. Likewise, its straightforward one-click interface wasn’t hugely innovative in itself even at the time — this doing-away-with the old menu of verbs was becoming the norm in graphic adventures by this point — but it is a well-executed example of such an interface. All in all, if you like traditional graphic adventures, you’ll find this game to be a sturdy, perhaps occasionally inspired example of the genre.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)