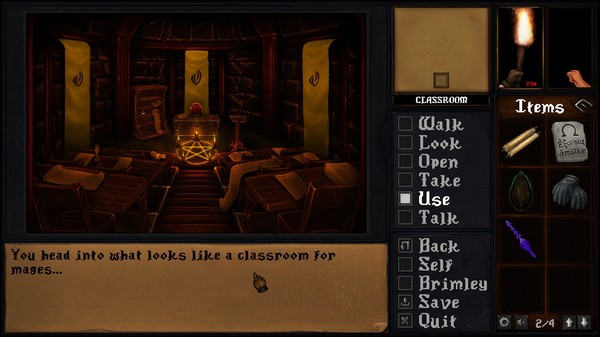

Although Grossman and Schafer were and are bright, funny guys, their game’s sparkle didn’t come from its designers’ innate brilliance alone. By 1993, LucasArts had claimed Infocom’s old place as makers of the most consistently excellent adventure games you could buy. And as with the Infocom of old, their games’ quality was largely down to a commitment to

process, including a willingness to work through the hard, unfun aspects of game development which so many of their peers tended to neglect. Throughout the development of

Day of the Tentacle, Grossman and Schafer hosted periodic “pizza orgies,” first for LucasArts’s in-house employees, later for people they quite literally nabbed off the street. They watched these people play their game — always a humbling and useful experience for any designer — and solicited as much feedback thereafter as their guinea pigs could be convinced to give. Which parts of the game were most fun? Which parts were less fun? Which puzzles felt too trivial? Which puzzles felt too hard? They asked their focus groups what they had tried to do that

hadn’t worked, and made sure to code in responses to these actions. As Bob Bates, another superb adventure-game designer, put it to me recently,

most of what the player tries to do in an adventure game is wrong in terms of advancing her toward victory. A game’s handling of these situations — the

elses in the “if, then, else” model of game logic — can make or break it. It can spell the difference between a lively, “juicy” game that feels engaging and interesting and a stubbornly inscrutable blank wall — the sort of game that tells you things don’t work but never tells you

why. And of course these

elsescenarios are a great place to embed subtle hints as to the correct course of action.

Indeed, Grossman and Schafer continually asked themselves the same question in the context of every single puzzle in the game: “How is the player supposed to figure this out?” Grossman:

That [question] has stuck with me as a hallmark of good versus bad adventure-game design. Lots of people design games that make the designer seem clever — or they’re doing it to make themselves feel clever. They’ve forgotten that they’re in the entertainment business. The player should be involved in this thing too. We always went to great lengths to make sure all the information was in there. At these “pizza orgies,” one of the things we were always looking for was, are people getting stuck? And why?

The use of three different characters in three completely different environments also helps the game to avoid that sensation every adventurer dreads: that of being absolutely

stuck, unable to jog anything lose because of one stubborn roadblock of a puzzle. If a puzzle stumps you in

Day of the Tentacle, there’s almost always another one to go work on instead while the old one is relegated to the brain’s background processing, as it were.

And yet, as in everything, there is a balance to strike here as well:

gating in adventure design is an art in itself. Grossman:

We were very focused on making things non-linear, but what we weren’t thinking about was that it’s possible to take that too far. Then you get a paralysis of choice. There’s kind of a sweet spot in the middle between the player being lost because they have too much to do and the player feeling railroaded because you’re telling them what to do. People don’t like either of those extremes very much, but somewhere in the middle, it’s like, “I’ve got enough stuff to think about, and I’m accomplishing some things, and I’ve got some new challenges.” That’s the right spot.

Day of the Tentacle nails this particular sweet spot, as it does so many others. It could never have done so absent extensive testing and — just as importantly — an open-mindedness on the part of its designers about what the testers were saying. It’s due to a lack of these two things that the adventure games of LucasArts’s rivals tended to go off the rails more often than not.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)