When is it OK to remake a classic game?

Adventure game remakes are common. But not everyone likes to see their old favourites revived. Mitch Kocen asked veteran point-and-clickmen Ron Gilbert and Tim Schafer, among others, when they think it’s OK to remaster the classics

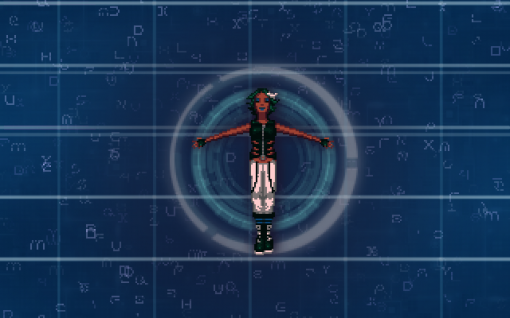

Without intervention, every video game you have ever loved will eventually become unplayable. The technology that enables the next generation of games cripples the last. At some point, systems simply can’t run slowly enough to support games made decades prior. For many years, it wasn’t possible to (legally) play older games without digging out the old computer gathering dust in your basement. Fortunately, there is a resurgence of classic games on modern hardware. These re-releases often come with new (or improved) graphics and sound, and sometimes include the option to view the game in its original form. Yet some creators are concerned that these changes compromise the game’s original artistic vision.

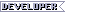

Ron Gilbert is one of them. The creator of

Monkey Island,

Maniac Mansion, and

Thimbleweed Park says that the sin of re-creating a game’s art is that the original artists made design choices motivated by what the technology allowed at the time. Changing the art undermines those decisions.

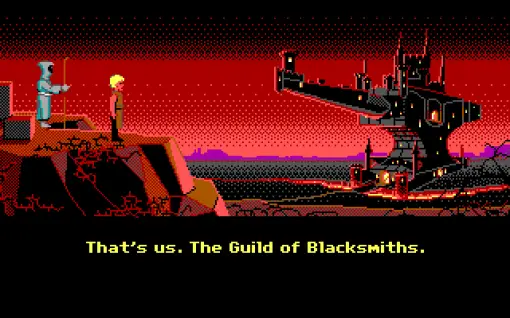

“We had limitations back then” recalls Gilbert in an email interview, “and the artist worked magic to make the game work within those limitations. They often turned working within those limitations into an art all its own. When classic games get ‘hi-resed’, you lose all of that.”

Gilbert, who led the design and writing of the Secret of Monkey Island, feels that remastered games should use the original art exclusively. Redecorating a classic game, he says, is like tampering with a black and white movie.

“When I hear about movies being remastered,” he says, “that usually involves going back to the original prints, cleaning them up, maybe correctly color balancing them, but it’s not fundamentally changing the aesthetics of the movie. It’s producing a clean copy of the original. That is what remastering games should be.”

Gilbert is not alone in thinking the original artistic intent matters to gameplay.

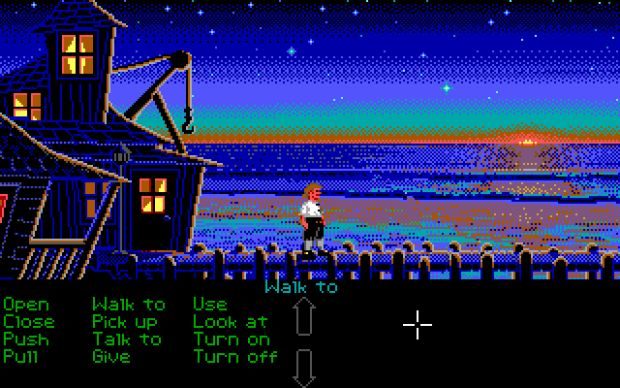

Loomdesigner Brian Moriarty first made his fantasy adventure game with the 16 colours available to his artists in 1990. But the design decisions they made would clash with the artistic possibilities granted by future technology, as he explains.

“The opening cut scene of Loom ends with Bobbin [the player’s character] standing on a cliff overlooking his village. Beside him is a tree bearing a single leaf. In the original 16-color EGA game, that leaf is the only object in the scene rendered in bright red.

“This is no accident… the leaf was placed there to teach players how to identify interactive objects, and to reinforce the melancholy tone of the game. It also insured that players would take note of the tree itself, which later becomes the boat Bobbin uses to escape the island.”

But when it came time in 1992 to re-release Loom with 256-colour graphics, the art team working on the port overlooked those intentions.

“In their eagerness to exploit the expanded palette,” says Moriarty, “the artist who repainted that scene ‘improved’ it by adding a reddish sunrise glow to the horizon behind the tree. The color gradation is pretty, but it makes the leaf less enticing as a target. Some players may miss it altogether.”

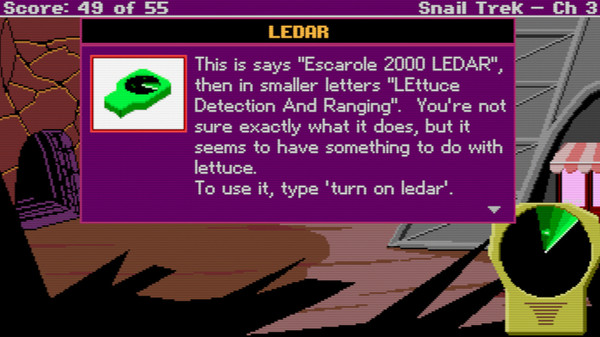

The last leaf of autumn might not seem like a big deal but by 2008, LucasArts had learned this lesson. They tasked producer Craig Derrick to form an internal team named “Heritage” to “reintroduce LucasArts’ back catalog and original IP’s to both new and nostalgic audiences.”

The Heritage initiative included the idea of keeping the original game alongside the remaster and being able to switch between the two during gameplay.

“Once we started getting the original code up and running on the new devices, we discovered we could put the new art on top of the old and then transition between the two seamlessly.

“It was a perfect A-HA moment, a bit of a gimmick, a way for people to see the work we were adding and quite frankly the backbone of the entire project. I honestly don’t see why anyone remastering a classic game today wouldn’t use this idea.”

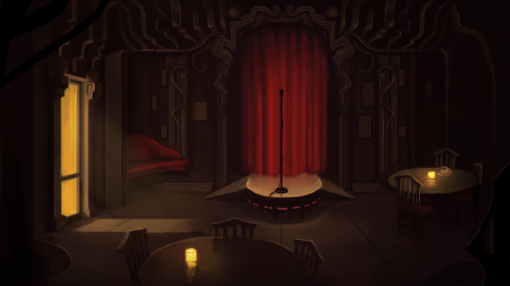

Tim Schafer agrees. The creator of

Grim Fandango, who also worked with Gilbert on the original Secret of Monkey Island, has produced well-received versions of classic LucasArts adventures through his current studio Double Fine Productions, while also working on newer adventures like

Broken Age.

“Remastering older titles is an important part of games preservation,” he says, “a satisfying project for the original creators, and nice thing to do for the fans.”

All of Shafer’s remakes include the original game, and he says he tries to ensure that the original creators are involved in the project, at least in some capacity.

“That way the remastered game is true to the original vision, but the players have the ultimate choice about how they want to play.”

Offering this choice to players doesn’t appease everyone. Gilbert still calls it a ‘sin’, sticking to his original analogy and comparing the classic point ‘n’ clicks of the 90s to the Hollywood classics of the 40s.

“It’s true that you can often switch back to the original graphics,” he says, “but that is also true of colorizing black and white movies.

“You can always watch the original, but that doesn’t make colorizing it any less of an artistic sin. Saying you can switch back to the original art feels like a cop-out.”

While Schafer, Derrick and others viewed the remakes as “a nice thing to do” or a way to “springboard the development of new adventure games”, Gilbert questions the motives.

“You have to honestly ask yourself, was this remaster done for artistic reasons or business reasons?”

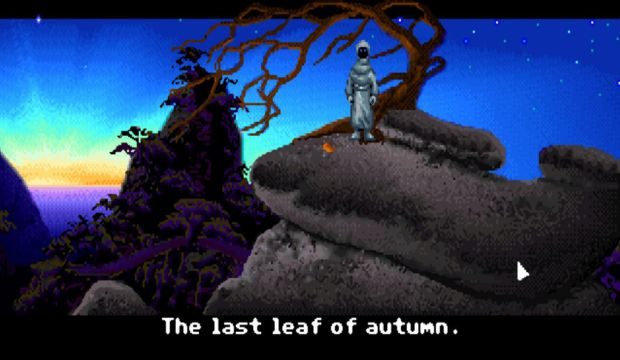

But if it’s money you’re after, it isn’t always necessary to paint over your past work, according to game preservationist Frank Cifaldi. He has worked with studio Digital Eclipse to create what he describes as “boutique packaging” of older games, like the

Mega Man Legacy Collection or

The Disney Afternoon Collection.

These are essentially bundles of faithfully emulated games complete with digital copies of old box art or forgotten manuals. It’s these special materials that catch people’s attention, says Cifaldi. It helps that his company make no changes whatsoever to the source material itself.

“It’s not really our place to do anything that wasn’t originally there, even if it’s correcting what we see as a mistake.”

While some classics are well-suited to this treatment, even Cifaldi concedes it isn’t an approach that will work for 95% of videogames.

Even though he feels emulation is the best way to experience a game as it was meant to be played, there remains a perception among players that emulation is a piracy tool. This causes people to “devalue” old games, he says, to the point where selling an emulated game becomes difficult.

“The consumer perception of that is: ‘oh, I can just pirate this. Why are you selling me a rom?’”

Brian Moriarty agrees that a straight remake isn’t always likely to be commercially successful. Buy the Loom creator says that strong special features can add enough value to justify a “purist” re-release, regardless of the fact it is essentially an emulation.

“I’d pay money for an authentic recreation of EGA Monkey Island, accompanied by live commentary by Ron Gilbert, Tim Schafer, Dave Grossman, Steve Purcell, Mark Ferrari, Aric Wilmunder, Michael Land and the other talented pioneers who put it all together,” he says.

I asked all of my interview subjects if they thought there was a market for classic games that remain ‘un-remastered’. The word that came up most frequently was “niche.” Some gamers do want to play these games exactly as they were, but not many – likely not enough to warrant the substantial licensing and development costs.

However, if we accept that videogames can be art (and I’m not interested in relitigating that argument here) then we have to preserve classic videogames by any means necessary. Ron Gilbert’s comparison of classic games to black and white films is a good way to ground the issue. Some people love to watch classic movies, some even prefer them to modern films. Others lose interest after a few minutes, turned off by the long takes, visual effects or lack of colour. They were raised with a different set of expectations for their entertainment. But a common thread among modern directors is that they love old movies. The same holds true for game developers. The people making modern hits grew up playing classic games and if we lost those games we would feel that absence as strongly as if we lost Citizen Kane or Psycho.

“Vintage games are lenses into the culture that produced them,” says Brian Moriarty “They are also reminders that it’s possible to create significant, influential work with very limited means.”

The argument from creators like Gilbert and preservationists like Cifaldi is valid, but short sighted. From an artistic standpoint, redoing graphics does compromise the original artists’ choices. Creators often bristle when someone else makes changes to their work. But taking such a hard line against redoing graphics might simply contribute to the extinction of classic games. If there’s not enough demand for a “pure” release then a modern remastering with an “original mode” is probably the best option. That practice is likely to continue indefinitely. In forty years, when Windows is as archaic as DOS is now, we might find Portal or Dead Space or Thimbleweed Park preserved in their original form too, as a bonus feature packaged with a VR or holodeck remake. You will be able to embrace the new graphics or hate them, but these projects will, like their counterparts today, essentially future-proof our classic games.

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)

![Have Many Potato [2013] Codex 2013](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_potato2013.png)