- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 99,690

Just 7/10 from PCGamesN, tsk tsk: https://www.pcgamesn.com/the-outer-worlds/review

The Outer Worlds review – funny business

Obsidian's latest RPG offers some spectacular moments, but buried in a great deal of connective tissue

Corporations have taken us beyond the bounds of our solar system, but the enterprises that built life on the galactic frontier have charged a heavy price. Business is now both god and king, as middle managers take on the roles of regional governors and a new religion preaches your place among the corporate gears. You’re going to do your job until you can afford the rental fees on your grave site, or you’re going to come out branded an outlaw.

In The Outer Worlds, you are very much one of those outlaws. Obsidian’s grimly satirical RPG puts you in the boots of a prospective colonist who’s freshly unfrozen after decades in suspended animation. But you’re the only one who’s awake. The Board – a bickering cabal of corporations that runs things in the colony – has left your colony ship to die, and you’ve only come through thanks to the somewhat-mad science of one Phineas Welles. The Board’s got secrets and Welles needs resources to awaken the rest of the frozen colonists, which leaves you to hop between the colonies in search of both answers and chemicals.

While The Outer Worlds has been compared to Fallout ever since its debut – a combination of retro-futuristic aesthetics, first-person roleplaying, and involvement from the series’ original creators will do that – in action it feels almost nothing like the Black Isle classics or the post-Bethesda open worlds. Instead, this comes across more like a lost mid-2000s BioWare game.

Most of the locations to which the main story points you are embroiled in some sort of conflict between a corporation and group living outside of the established rules. Your goals will usually intersect with those rivalries, leading you through a spiral of intertwining side-quests until you finally get to pick a side in a grand moral choice at the end of that chapter of your adventure. In other words, in the Obsidian pantheon this follows Knights of the Old Republic II much more closely than Fallout: New Vegas.

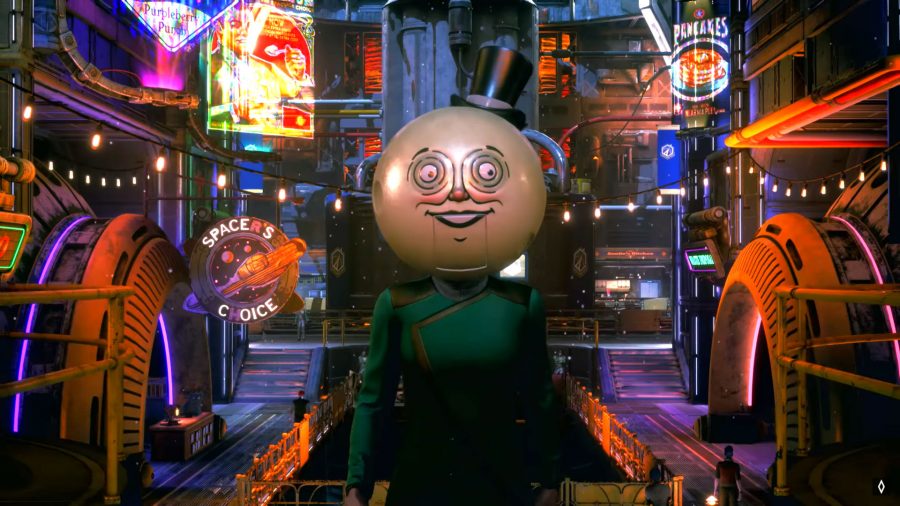

The first big decision leaves you stuck between the Spacer’s Choice corporate colony and a group of rebels who’ve chosen to live at an outpost outside the city walls. You need a power drive to get off the planet, and you can only get it by sneaking into a power plant and shutting down the, err, power to one side or the other. There’s a bit of lip service paid to the idea that this is a tough choice, since shutting down the corporation’s energy source will leave a whole bunch of people out of jobs – but then you’ve also just spent hours watching Spacer’s Choice bear down and exploit its employees as only a hilariously corrupt megacorp can.

It ends up being a decision between good with a bit of hardship, or absolute moustache-twirling evil (but at least the trains run on time). Other choices offer more nuance, but the writing is often at odds with itself – sometimes you’re in an intricately detailed, serious sci-fi world where everyone will suffer profound consequences as a result of your actions, while other moments put you in the midst of a bleak-but-ridiculous anti-corporate comedy.

There are great moments at either end of The Outer Worlds’ tonal spectrum, and the payoffs are usually fantastic. There’s the loyal corporate salesman whose reward for service is a silly moon mask and a lifetime of spouting half-hearted slogans. There’s the philosophical war between an idealist rebel captain, his pragmatic compatriot who just wants to keep the people fed, and their counterpart inside the city walls who wants to build change under the Board’s rule.

There are bits that are laugh-out-loud funny – like when you’ve got to collect grave rental fees from somebody who’s already dead – and others that are earnestly heartwarming, such as when you facilitate the first date of one of your party members. There are fantastic pieces throughout, certainly, but the tonal confusion makes it tough to stay invested in the story and characters through all of the resultant connective tissue.

These portions tend to be the least interesting parts outside of the dialogue trees, too. The bigger worlds where you’ll spend most of your time are made up of densely packed points of interest like cities, outposts, and hideouts, spread out across the wilderness of a big, mostly open-ended map. These wilderness areas are where the game most feels like modern Fallout, but since your objectives are predominantly dictated by the quests you find, they don’t have the same sense of discovery – it’s just a bunch of the same few collections of bandits and wild beasts to wade through until you reach the next interesting location. A generous fast travel system at least means you don’t have to hike through the same area twice.

Combat puts you in that awkward middle ground between FPS and RPG, but there’s just enough depth to your roleplaying abilities to make up for the fact that the game doesn’t feel like a dedicated shooter. You can slow down time at the press of a button – amusingly, the result of head trauma you suffer in the tutorial – which lets you examine enemies to see their strengths and weaknesses. The meter that governs this ability is basically frozen until you move, so you can sit for a moment, consider your actions, then line up a couple of headshots or crippling leg shots before returning to real-time combat to mop up.

Skill points determine your effectiveness with various weapon types, and the more substantial perks that you get every other level let you create some pretty unusual builds. I struggled early on against armoured enemies, since I could never hang onto enough heavy ammunition to take them down, until I got a perk that let me knock off a point of an enemy’s armour rating with every ranged shot. From then on, simply dumping a light handgun clip into just about any enemy was sufficient to soften it up for the kill.

There are a lot of fun little mechanics around the edges which help to add some life to combat that would otherwise be pretty familiar. Science weapons that you pick up through side-quests don’t deal the damage of their conventional counterparts, but they will let you do everything from launching marauders into the air to shrinking massive insects down to proper ant size.

Each party member has a single unique ability, too. These all briefly pause the action for a cutscene, while your ally readies a weapon, deals some damage, and applies a temporary debuff to the foe you’ve sent them against. While the animations never change, they also rarely get old – at least, I never got tired of watching my world-weary preacher smite bad guys with a shotgun while reciting his holy book.

Despite all the freedom to roam, The Outer Worlds is at its best in its most constrained locations – facilities, caverns, and ruins filled with powerful enemies and multiple paths. These sections feel almost like miniature Thief or Dishonored-style immersive sims, giving you a clear objective and loads of ways to go about achieving it. You can shoot your way through just about anything, sure, but you can also use stealth. You can hack computers to turn off security systems, or if you’ve got that skill high enough, you can turn the robotic defenders against their masters. You can almost always talk your way out of a boss fight. And sometimes, the optional quests you’ve done leading up to one of these locations can give you unexpected allies as you go.

That’s a familiar list of options if you’ve played any open-ended RPG of the past few decades, but it’s in these de facto dungeons where the character you’ve built, the skills you’ve chosen, and the playstyle you’ve gone for really come together. It feels great, and it also helps that these sequences usually come at the conclusion of major plot arcs – so right as you’re feeling good about the choices you’ve made for your build, you’re also seeing the results of all the dialogue decisions you’ve been making over the previous few hours, and everything comes together in an often spectacular little package.

The Outer Worlds falters in that there just aren’t enough of these moments. That leaves you playing hours of ‘good’ just to get to that 30-minute stretch of ‘great.’ That’s not a terrible ratio – especially as my fairly complete playthrough clocked in around 25 hours, not especially long as RPGs go – but it often feels that the game isn’t living up to its full potential.

But while most of the elements that make up The Outer Worlds sit between ‘good enough’ and ‘great,’ there’s one legitimate bad point: the UI. You can only track one quest at a time, which is frustrating when you’ll often have three or four to attend to in the same location, and the only way to establish which is which is to track one, find it on the map, then go back to track the others and repeat the process. Inventory management is similarly frustrating – it’s way more difficult than it needs to be to compare equipment, the upgrade and mod systems take far too much time to sort through compared to the benefits they provide, and all of your normal sorting options for some reason disappear while you’re equipping party members.

Even so, while Obsidian’s garnered quite a reputation for buggy games at launch, I didn’t run into many major technical issues during my time with the game. Well, not until the very end, at least – a single, repeatable crash during the game’s final sequence was the only bug I hit, but it was one that I could only get around by killing an NPC I’d much rather have talked to. That’ll surely get an eventual patch, and while it was disappointing in the moment, this is a much better technical showing than the studio has historically put forward.

Much like the potential rewards from a life at the edge of the galaxy, then, despite some hardships along the way The Outer Worlds is a journey worth undertaking.

The Outer Worlds review

Obsidian’s RPG fulfills its potential, but only in fits and starts. Sure, its worst moments are only ever as bad as workmanlike RPG-making, but they make the stretches between some instances of genuine greatness a little more disappointing.