-

Welcome to rpgcodex.net, a site dedicated to discussing computer based role-playing games in a free and open fashion. We're less strict than other forums, but please refer to the rules.

"This message is awaiting moderator approval": All new users must pass through our moderation queue before they will be able to post normally. Until your account has "passed" your posts will only be visible to yourself (and moderators) until they are approved. Give us a week to get around to approving / deleting / ignoring your mundane opinion on crap before hassling us about it. Once you have passed the moderation period (think of it as a test), you will be able to post normally, just like all the other retards.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Red Dead Redemption 2 - now available on PC

- Thread starter Morgoth

- Start date

So it's exactly as expected - a Witcher 3-like interactive movie about running from point A to point B and watching pretty cutscenes. Hey, you can't overexert players if you don't exert them right?

Yeah. Not a mention about not being able to play a female character. #NotMyKotaku

Archive that shit.I liked this review: https://kotaku.com/red-dead-redemption-2-the-kotaku-review-1829984369

Yeah. Not a mention about not being able to play a female character. #NotMyKotaku

I guess the Kotaku guy wrote so much in the hope that he will get noticed and hired as a janitor at rockstar.

The Kotaku Review

Cuck Cuckington

Today 7:01am

•Filed to: REVIEW

614

From tip to tail, Red Dead Redemption 2 is a profound, glorious downer. It is the rare blockbuster video game that seeks to move players not through empowering gameplay and jubilant heroics, but by relentlessly forcing them to confront decay and despair. It has no heroes, only flawed men and women fighting viciously to survive in a world that seems destined to destroy them.

It is both an exhilarating glimpse into the future of entertainment and a stubborn torch bearer for an old-fashioned kind of video game design. It is a remarkable work of game development and, possibly, a turning point in how we remark upon the work of game development. It is amazing; it is overwhelming. It is a lot, and also, it is a whole, whole lot.

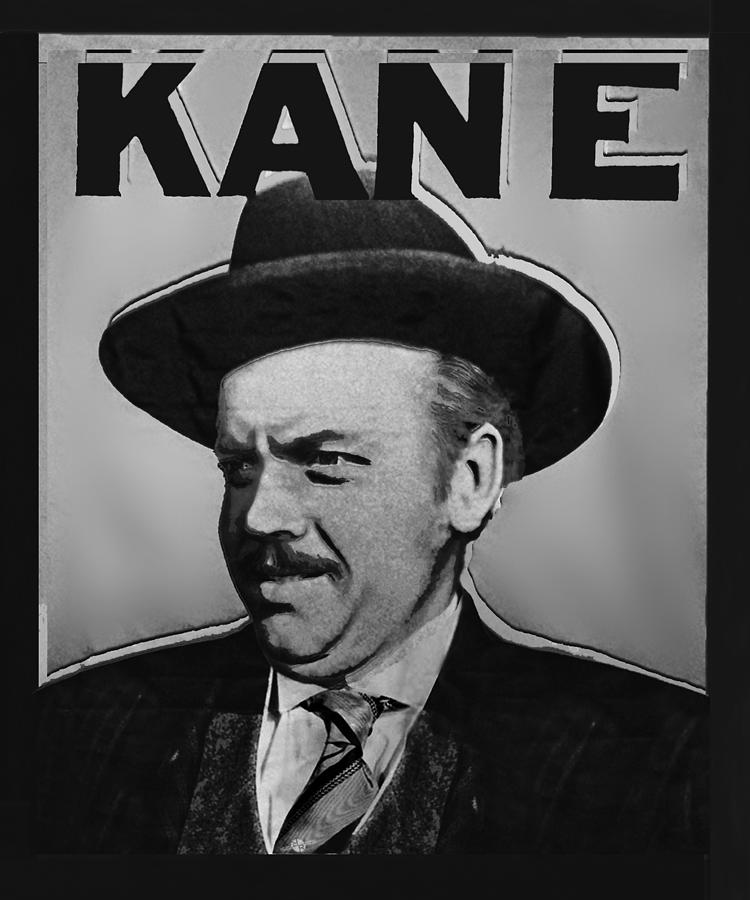

View attachment 9986

Rockstar Games’ new open-world western opus is exhaustively detailed and exhaustingly beautiful, a mammoth construction of which every nook and cranny has been polished to an unnerving shimmer. It is a stirring tribute to our world’s natural beauty, and a grim acknowledgment of our own starring role in its destruction. It tells a worthy and affecting story that weaves dozens of character-driven narrative threads into an epic tapestry across many miles and almost as many months. When the sun sets and the tale has been told, it leaves players with a virtual wild-west playground so convincingly rendered and filled with surprises that it seems boundless.

It is defiantly slow-paced, exuberantly unfun, and wholly unconcerned with catering to the needs or wants of its players. It is also captivating, poignant, and at times shockingly entertaining. It moves with the clumsy heaviness of a 19th century locomotive, but like that locomotive becomes unstoppable once it builds up a head of steam. Whether intentionally or not, its tale of failure and doom reflects the tribulations of its own creation, as a charismatic and self-deluded leader tries ever more desperately to convince his underlings to follow him off a cliff. Paradise awaits, he promises. Just push a little bit further; sacrifice a little bit more; hang in there a little bit longer.

View attachment 9989

Such a masterful artistic and technical achievement, at what cost? So many hours of overtime crunch, so many hundreds of names in the credits, so many resources—financial and human—expended, for what? What was the collective vision that drove this endeavor, and what gave so many people the will to complete it? Was it all worth it in the end?

After 70 hours with Red Dead Redemption 2, I have some thoughts on those questions, though I do not find my answers satisfactory or conclusive. What I can say for sure is that the sheer scale of this creation—the scale of effort required to create it, yes, but also the scale of the thing itself, and the scale of its achievement—will ensure that those questions linger for years to come.

View attachment 9990

Red Dead Redemption 2 is a follow-up to Red Dead Redemption. Let’s just start there, with the most basic and true thing that can be said of this game. Yet even that laughably obvious statement contains more meaning than it might first seem, because the new game is so spiritually connected with its predecessor. It nestles so neatly with the 2010 game that the two could have been concurrently conceived. It takes the same characters, narrative themes, and game design ideas introduced in the original and refines, elaborates, and improves on them all. Yet the two are more than separate links in a chain of iteration; just as often, they are complementary halves of a whole.

While new and improved in terms of design and execution, Red Dead 2 is narratively a prequel. The year is 1899, a decade before the events of the first game. Again we take control of a steely-eyed gunslinger in a wide-open, abstracted version of the American West. Again we are given free rein to explore a vast open world however we please. Again we meet a cast of colorful characters, and again we watch those characters contemplate the cost of human progress and yearn for the half-remembered freedoms of a mythic, wild past. Again we ride our horse across forests and deserts and plains; again we shoot and stab and decapitate untold scores of people. Again we can lasso a dude off the back of his horse, tie him up, and throw him off a cliff.

View attachment 9985

Our hero this time around is a weathered slab of handsome named Arthur Morgan. He’s a taciturn type who looks like Chris Pine cosplaying the Marlboro Man, and a respected lieutenant in the notorious Van der Linde gang. Arthur was taken in by the gang as a kid and raised on violence, but is, of course, blessed with an antihero’s requisite softer, thoughtful side. He’ll kill a man for looking at him wrong, but he’s oh so affectionate with his horse. He’ll beat an unarmed debtor nearly to death at the behest of a colleague, but he sketches so beautifully in his journal.

At first Arthur struck me as deliberately unremarkable, another grumbling white-guy tabula rasa onto which I was meant to project my own identity. By the story’s end, I had come to see him as a character in his own right, and a fine one at that. Actor Roger Clark brings Arthur to life with uncommon confidence and consistency, aided by a sophisticated mix of performance-capture wizardry, top-shelf animation and character artistry, and exceptional writing. Each new trial he survives peels back a layer from his grizzled exterior, gradually revealing him to be as vulnerable, sad, and lost as the rest of us.

Arthur may be the story’s protagonist, but Red Dead Redemption 2 is an ensemble drama. The Van der Linde gang is more than just another Pekinpah-esque clutch of scoundrels on horseback; it’s a community, a mobile encampment consisting of about 20 men, women, and children, each with their own story, desires, and role. There are villains and psychopaths, drunks and miscreants, and also dreamers, runaways, and lost souls just looking to survive. Each character has their own chances to shine, particularly for players who take the time to get to know them all. From the cook to the layabout to the loan shark, each has become real to me in a way fictional characters rarely do.

View attachment 9988

At the head of the table sits Dutch van der Linde, as complex and fascinating a villain as I’ve met in a video game. Benjamin Byron Davis plays the boss man perfectly, imagining Dutch as a constantly concerned, watery-eyed killer. He just cares so much, he is doing everything he can, his voice is perpetually on the edge of cracking out of concern. Not concern for himself, mind, but for you, and for all the other members of this family of which he is the patriarch. It’s all bullshit, of course. Dutch is a coward and a fool, and all the more dangerous due to his capacity for self-deception. He’s the kind of man who would murder you in your sleep, then quietly weep over your corpse. You will never know how much it hurt him to hurt you.

The name “Dutch van der Linde” should ring an ominous bell for anyone who played 2010’s Red Dead Redemption and remembers how it ends. Because Red Dead 2 is a prequel, those familiar with its predecessor have the benefit of knowing how the saga will conclude. (If you missed the first game or it’s been a while, I recommend watching my colleague Tim Rogers’ excellent recap video.) That knowledge is indeed a benefit, to the point that I will outline many of the first game’s broad strokes (including spoilers!) in this review. My familiarity with the original greatly helped me appreciate the many ways the sequel encircles and elaborates upon its other, earlier half.

We know that the gang will eventually fall apart; we know that Dutch will lose his way and his mind. We know that John Marston, seen in this sequel as a younger, greener version of the man we played as in the first game, will one day be forced to hunt down and kill his surviving compatriots, including Dutch. We know that John will die, redeemed, while protecting his family. And we know that John’s son Jack is doomed to take up his father’s mantle of outlaw and gunslinger. Red Dead Redemption 2 busies itself with showing how things got to that point. Our foreknowledge adds considerably to the sequel’s already pervasive sense of foreboding, and routinely pays off in often subtle, occasionally thrilling, ways.

View attachment 9987

Things look grim from the start. The gang is hiding out in the mountains, on the run from the law after a botched bank robbery left them penniless, down a few men, and with a price on all their heads. After surviving a brutal early spring in the snow, Dutch, Arthur, and the rest of the crew set about rebuilding a new encampment in the green meadows near the town of Valentine. “Rebuilding” really means robbing and looting, of course, and things inevitably escalate. The gang’s antics eventually bring the law down on them, forcing them to relocate yet again. Thus the narrative finds its structure, driven by the wearying rhythms of escalation, confrontation, and relocation. The caravan is driven east—yes, east—through grasslands and plantations, to swamps, cities, and beyond.

Each time they move, Dutch promises that things will be different. This time, they’ll find their peaceful paradise and settle down. If they can just get some money, of course. If they can just pull off one big score. You understand, don’t you? What would you have him do? His lies become increasingly transparent the more emphatically he tells them. Dutch is selling the dream of an “unspoiled paradise” without acknowledging that he and his gang spoil everything they touch. By the end, his hypocrisy has become sickening, and the many ways Arthur and his fellow gang members wrestle with and justify their continued allegiance to Dutch undergird some of Red Dead 2’s most striking and believable drama.

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-medi...ogressive,q_80,w_800/fsxn8vfkl5h1f3obd9qf.mp4

As you ride from place to place, you can activate a “cinematic camera” that will overlay black bars onto the screen and steer for you, provided you’ve selected a destination. These journeys approach photorealism to an eerie degree.

Red Dead Redemption 2 is set in a version of America that is both specific and abstracted. Characters routinely speak of real places like New York City, Boston, and California, but the actual locations in the game are broadly drawn stand-ins. “The Grizzlies” are basically the Rocky Mountains, the state of “Lemoyne” is more or less Louisiana, and the bustling city of “Saint Denis” is based on New Orleans. There are no real historical figures to meet or talk with in this game, though it is still clearly the result of copious research and attention to period accuracy.

As with the first Red Dead, the world’s fictional duality puts the story in a gently abstracted space that allows the writers to comment on American history without worrying overmuch about historical accuracy. Were Red Dead Redemption 2 loaded with cheap satire and eye-rolling commentary, that approach would come across as a frustrating bit of ass-covering. Fortunately, thanks to the game’s strong script, it instead frees the game up to paint in strokes broad enough to capture the oppressive corruption that continues to be one of our nation’s defining aspects.

Time and again I was struck by how seriously this game’s writers took their characters, themes, and subject matter. Abstract or no, Red Dead 2’s America is still a nation reeling from the Civil War, where women are not allowed to vote, and where Native Americans and their cultures are being systematically eradicated. Everything in the main narrative is treated with appropriate weight and humanity, and never did I encounter a lapse into the sort of haphazard satire and “everyone sucks” cop-outs embraced—by some of the same writers!—in Rockstar’s depressingly misanthropic Grand Theft Auto series.

These characters are all people, and they’re dealing with things people dealt with at the turn of the century in America. Their lives were hard, and most of their stories ended badly. That’s just how it went. Precious moments of kindness and generosity seem all the more precious against that dark backdrop, but even those are few and far between. What starts outside Valentine as a dreamy cowboy fantasy quickly becomes a weary parable about entropy, villainy, and the death of a lie.

Dutch’s gang lives at the fringes of society, out in the sort of untamed wilderness that, in 2018, is becoming harder and harder to find. Red Dead Redemption 2 contains the most bracingly beautiful depictions of nature I have ever seen in a video game, and is happy to juxtapose that beauty with the ugly, violent human ambition that will eventually subjugate and destroy it.

There is something ironic about a technologically stunning piece of digital entertainment in which the characters constantly lament the relentless progress that will eventually lead to the development of the television and the microchip; the very progress that will allow video games like this one to exist. It reveals something deep and true about our conflicted consumer culture, that some of its finest art righteously castigates the very systems that brought it into being. Red Dead Redemption 2 may be ultimately—or even necessarily—unable to resolve that paradox, but it is more than willing to embrace and attempt to dismantle it.

View attachment 9991

The world of Red Dead Redemption 2 is expansive and engrossing, even while—and often because—the process of interacting with it can be frustrating and inconsistent. Its overwhelming visual beauty invites players in, but its sludgy kinesthetics, jumbled control scheme, and unclear user interface keep them at arm’s length. That artificial distance goes against many commonly understood game design principles, yet also works to help perpetuate the convincing illusion of an unknowable parallel world.

I only rarely found Red Dead 2 to be “fun” in the way I find many other video games to be fun. The physical act of playing is rarely pleasurable on its own. It is often tiring and cumbersome, though no less thrilling for it. No in-game activity approaches the tactilely pleasing acts of firing a space-rifle in Destiny, axing a demon in God of War, or jumping on goombas in Super Mario Bros. Red Dead 2 continues Rockstar’s longstanding rejection of the notions that input response should be snappy, that control schemes should be empowering and intuitive, and that animation systems should favor player input over believable on-screen action.

Pressing a button in Red Dead 2 rarely results in an immediate or satisfying response. Navigating Arthur through the world is less like controlling a video game character and more like giving directions to an actor. Get in cover, I’ll tell him, only to see him climb on top of the cover. Did I press the button too late? Did my button-press register at all? Dude, get down, I’ll cry, as his enemies begin to open fire. He’ll slowly wheel around, then slide down to the ground with an elaborate stumbling animation. GET IN COVER, I’ll command, pressing the “take cover” button for what feels like the sixth time. He’ll haul his body weight forward, then finally crouch behind the wall.

View attachment 9996

Arthur’s horse adds yet another degree of remove. With a press of a button, Arthur coaxes his horse forward. Pressing it rhythmically in time with the horse’s hoofbeats causes him to urge the horse to a gallop. But you’re still controlling the man, not the horse. Mind your direction, for it is perilously easy to broadside a passing civilian and instigate a firefight, or to collide with a rock or tree, sending man and horse careening catawampus to the ground. Red Dead 2’s horses are meticulously detailed and gorgeously animated, and move through the world like real animals, right up until they don’t. Get too close to a boulder or crosswise to a wagon, and the realistic facade crumbles, leaving you with a grouchy, unresponsive horse with its head clipping through a tree.

Almost every interaction must be performed through the same gauzy, lustrous cling-wrap. Firefights are chaotic and random, and aiming often feels wild and unmanageable. Rifles require separate trigger-pulls to fire and to chamber a new round. Enemies move quickly and melt into the world’s overwhelming visual milieux, and my resulting reliance on the heavily magnetized aim-assistance turned most fights into pop-and-fire shooting galleries. Arthur moves slowly, particularly while in settlements or indoors. It’s also possible to make him run too fast, crashing through doors and into civilians. Navigating this world is arduous, heavy, and inelegant. Even the simple act of picking an object up off the floor can require two or three moments of repositioning and waiting for an interaction prompt.

In a Rockstar first, every character and animal in Red Dead 2 can be interacted with in a variety of nonviolent ways. Usually that means you look at them, hold the left trigger, then select to “greet” or “antagonize” to govern what Arthur says. After antagonizing, you can antagonize further or “defuse,” and see where things go from there. Characters may ask you a question or request your help, after which highlighting them will give you the chance to choose a response. Like Arthur’s physical interactions, these conversational systems feel awkward and unknowable, yet introduce another fascinating avenue of unpredictability. If I antagonize this guy, will he cower or attack me? If I try to rob this lady, will she acquiesce or, I don’t know, kick me in the nuts?

Break the law even mildly while in view of a law-abiding citizen, and they’ll run off to report you. Tarry too long, and a posse will show up and accost you. They may not immediately open fire, instead drawing their weapons and instructing you to keep your hands up. Might they let you go with a warning? Might they arrest you? Or might they shoot first and ask questions later? I’ve had different outcomes in different towns, with different sheriffs, after commiting slightly different crimes. Which was the variable that changed things? I can’t say for sure. By and large that ambiguity enhances the experience, rather than detracting from it.

View attachment 9997

The entire game can be played from a first-person perspective, which is impressive and often overwhelming.

Unlike so many modern open-world games, Red Dead Redemption 2 does not want you to achieve dominance over it. It wants you to simply be in its world, and to feel like a part of it. It’s a crucial distinction, and a big part of what makes it all so immersive and engrossing. The thrill of playing Red Dead 2, like with many other Rockstar games, comes not from how fun or empowering it feels on a moment to moment basis. It comes from the electric sense that you are poking and prodding at an indifferent, freely functioning world.

Every interaction in the game, from gunfights to bar brawls to horse races, feels fundamentally unknowable. The slightest mistake or change in course can lead to wildly variable outcomes. That unknowability gives every undertaking an air of mystery that, combined with the incredible level of detail in every square inch of the world, stoked my imagination to begin filling in the gaps. Did this character in town really remember me from the last time I visited, several hours ago? Or was that just the result of a clever bit of scripted dialogue? Is there some hidden system governing who likes me and doesn’t like me, or am I imagining things? Will it really lower my chances of getting arrested if I change my clothes after a bank heist, or is wearing a bandana over my face enough? If I go out in the woods with blood on my clothes, will it attract bears?

Those types of questions lurk behind every moment with Red Dead Redemption 2, igniting the game world with the spark of the player’s own imagination. Most modern video games are eager to lay it all out in front of you. They put all the abilities, ranks, levels, and progression systems in a spreadsheet for you to gradually fill out. With Red Dead 2, Rockstar has ignored that trend, opting instead to obfuscate numbers at almost every opportunity. When the game does embrace numerical progression systems, as with the newly expanded leveling system tied to health, stamina, and “dead-eye” slow-mo aim, those systems are often confusingly laid out and poorly explained. Those weaknesses emphasize Red Dead 2’s greatest strength: that it is less an easily understandable collection of game design systems and more an opaque, beguiling world.

Here’s a story. It’s dumb, and short, and could stand in for a hundred other similar stories I could tell. After Arthur and the gang came down from the mountains, I found myself finally set loose in the open meadows outside the town of Valentine. I guided my horse away from camp along the road, stopping at the post office outside town. After hitching up and dismounting, I saw a prompt in the corner of the screen indicating that I could “search saddlebag.” Not knowing what that meant, I pressed the button, only to realize with horror that Arthur was reaching not into his own saddlebag, but into the one draped over a stranger’s adjacent horse. I scarcely had time to react before this happened:

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-medi...ogressive,q_80,w_800/qgp52urqjr8lqhof1be8.mp4

I almost fell out of my chair with surprise. Arthur hastily backed away from the horse, his left half freshly disheveled and covered in mud. I had only just gotten to town, and I already looked a mess! Thrown for a loop and unsure what to do next, I wandered toward the post office. I watched a passing man pick his nose and eat it.

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-medi...ogressive,q_80,w_800/h7ja7ugib8wmd4i7z4wz.mp4

As I walked through the post office, I overheard a woman remark, “I hope that’s only mud on you.” Looking at myself more closely, I wasn’t so sure. I left the building and headed up toward town, still bathed in filth. I went into a bar and instigated a cutscene, throughout which Arthur remained covered in now-slightly-dried mud.

View attachment 9992

I left the bar, only then realizing that Arthur was no longer wearing his hat. A wild west gunslinger needs his hat! Of course, it must have fallen off when the horse kicked me. I rode back to the post office and yep, there it was, lying in the mud.

View attachment 9998

I picked up the hat, put it back on, and rode back to town. Was that experience fun? Not exactly. Was it rewarding or empowering? Quite the opposite. It began with the game violently reacting to an action I hadn’t intended to take. It ended with some backtracking to retrieve a hat that I later would learn I could’ve just magically conjured from my horse. But was it memorable? Was it something that could only have happened in this game? Did it make me laugh, shake my head in amusement, and wonder what small adventure or indignity I might stumble into next? It sure did.

At every opportunity, Red Dead Redemption 2 forces you to slow down, take it easy, drink it in. Try to move too fast, and it will almost always punish you. Its pace is outrageously languid compared with any other modern game, especially in its first half. I spent a good chunk of my time just riding from place to place, and once I got where I was going, often went on to engage in extremely low-key activities.

View attachment 9994

Geralt, is that you?

Over and over it favors believability and immersion over convenience. Looting an enemy body instigates an involved animation that takes several seconds to complete. Washing your character requires you to climb into a bath and individually scrub your head and each of your limbs. Skinning a dead animal involves a prolonged animation during which Arthur carefully parts the creature’s skin from its muscles before carrying the hide, rolled up like a carpet, over to his horse. You can also choose not to skin the animal and instead cart its entire corpse to the butcher. Don’t leave it tied to the back of your horse for too long, though, or it will begin to rot and attract flies.

That consistently imposed slowness forced me to slow down and take in what is arguably this game’s defining characteristic: an incredible, overwhelming focus on detail.

View attachment 9993

Red Dead Redemption 2 lives for details. Were you to create a word-cloud of every review published today, the words “detail” and “details” would almost certainly feature prominently alongside “western” and “gun” and “horse testicles.” It’s impossible not to obsess over the level of detail in this game, from the incredibly detailed social ecosystem of its towns, to the ludicrously elaborate animations, to the shop catalogues and the customizable rifle engravings and on, and on, and on.

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-medi...ogressive,q_80,w_800/cez7lipzttcb5tzonuxw.mp4

Let’s start with foliage. I mean, why not? We could start anywhere, so let’s start there. The foliage in this game is fucking transcendent. It is hands-down the most amazing video game foliage I have ever seen. When you walk past it, it moves like foliage should. When you ride through it, Arthur reacts like a person on a horse would probably react to foliage. Even after all these hours, I am still impressed by the foliage.

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-medi...ogressive,q_80,w_800/cyaevpc9e1dh9zh6x1ae.mp4

I could talk about the foliage for another four paragraphs, which illustrates how difficult it is to capture the volume and variety of astonishing details in this game. Every weapon and every outfit is accompanied by a fully written, lengthy catalog entry. The fantastic (entirely optional!) theatrical shows you can attend are performed by what appear to be actual motion captured entertainers—the drummer in a proto-jazz band moves his sticks realistically, matching snare and cymbal hits flawlessly to the music, and I am convinced that Rockstar hired a professional fire dancer to come and perform in their mocap studio.

Seemingly every minute reveals yet more surprises. Once a man picked my pocket, so I shot him in the leg as he fled. He carried on, limping, until I caught him. Once I randomly struck up a conversation with a disabled Civil War vet who said he remembered me from the last time we talked, which led to an extended, apparently unique conversation concerning Arthur’s life and feelings about what was currently happening in the story. Once I shot at a bandit who was chasing me and accidentally hit his horse, then watched in horrified awe as his horse flipped over onto its face, tripping up the man riding behind him and leaving them in a tumble of limbs and blood.

//kotaku.com/embed/video/iframe?id=mcp-3588594&post_id=1829984369&blog_id=9&platform=embed&autoplay=false&mute=false

Above: Kotaku video producer Paul Tamayo highlights more of the game’s amazing details.

Once, while riding alongside another character in a snowstorm, I realized that if I drew further away from my compatriot, both characters would begin to yell; as I got closer, they returned to their regular speaking voices. After Arthur finished butchering a turkey, I noticed that his right hand remained covered in blood. “I hope that’s not your blood,” a man subsequently said to me as I passed. (Later it rained, and the blood washed off.) Another time, Arthur took off his gun belt before boarding a riverboat casino, and the entire process was fully animated.

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-medi...ogressive,q_80,w_800/yxoz2g8kljujvyz03jrr.mp4

When other games would crop the difficult-to-animate thing out of the frame, Red Dead Redemption 2 shows it in all its glory.

Those are all examples of something I’ve come to think of as “detail porn.” Video game detail porn is huge on the Internet. People love to share tiny, amazing details from their favorite games, holding them up as praiseworthy evidence of the developers’ hard work and determination. I’ve indulged in my share of detail porn-mongering over the years, mining pageviews and Twitter likes from Spider-Man’s voiceover work, Tomb Raider’s weirdly impressive doorway transition, Horizon Zero Dawn’samazing animations, Assassin’s Creed Odyssey’s ridiculous helmet physics, and even the absurdly detailed revolver hammers in a Red Dead 2promotional screenshot. This game will inspire more detail porn than any since Rockstar’s own Grand Theft Auto V. Its incredible focus on minutiae plays an integral role in making it such an overloading and engrossing experience, and often left me marveling at how such a feat of artistic engineering could be completed at all.

How did they do this? I asked myself, over and over again. There are answers to that question, of course. Each one raises many more questions of its own.

It has long been an open secret in the games industry that Rockstar’s studios embrace a culture of extreme work, culturally enforced “voluntary” overtime, and prolonged periods of crunch. The “secret” part of that open secret evaporated somewhat over the past week, as a controversial comment by Rockstar co-founder and Red Dead Redemption 2writer Dan Houser set off a cascade of revelations about work conditions at the notoriously secretive company.

Over the past month, my colleague Jason Schreier spoke with nearly 90 current and former Rockstar developers, and his report on the matterpaints a picture of a vast and varied operation that, for all its talk of change, has clearly spent years embracing and profiting off of a culture of exorbitant overwork that even many who say they are proud to work at Rockstar want to see changed.

Play Red Dead Redemption 2 for just a few minutes, and the fruits of that labor will be immediately apparent. This wonderful, unusual game was clearly a titanic logistical undertaking. Every cutscene, every railroad bridge, every interior, every wandering non-player-character has been polished to a degree previously only seen in more limited, linear games. If Naughty Dog’s relatively constrained Uncharted 4 required sustained, intense crunch to complete, what must it have taken to make a game a hundred times that size, but with the same level of detail? As critic Chris Dahlen once put it while ruminating on how much easily missable, painstakingly sculpted work is included in the average big-budget game, “That’s some fall of the Roman Empire stuff right there.”

I sometimes struggled to enjoy Red Dead Redemption 2’s most impressive elements because I knew how challenging—and damaging—some of them must have been to make. Yet just as often, I found myself appreciating those things even more, knowing that so many talented people had poured their lives into crafting something this incredible.

Watching Red Dead Redemption 2’s 34-minute credits sequence was a saga all on its own. I’ve watched (and skipped) countless lengthy credits sequences in my years playing video games, but this time I decided to really pay attention, to try to get a real sense of the scope of this eight-year production. First came the names one tends to associate with a game and its overall quality; the executive producers, the studio heads, the directors. Right at the top were the writers, Dan Houser, Michael Unsworth and Rupert Humphries, whose substantial efforts resulted in such a fine script filled with such wonderful characters.

Soon thereafter came the technical credits, which began to give a fuller sense of the many, many people who brought this game to life. Here was the “lead vegetation artist,” JD Solilo, joined by 10 other vegetation artists. Becca Stabler’s name was in a bigger font than Rex Mcnish’s, but which of them was responsible for that bush in the GIF I made? Maybe they’d tell me they weren’t responsible at all, and that it was really the engineers who rigged it up.

After that came Rod Edge, director of performance capture and cinematography, atop a list of directors and camera artists responsible for making those cutscenes so lifelike and believable. Then came audio director Alastair Macgregor, whose team created a sonic landscape that occasionally inspired me to just close my eyes and lose myself, and who stitched Woody Jackson’s pitch-perfect musical score so seamlessly into the world around me. Who made the rain; who crafted the thunder? Was it George Williamson or Sarah Scott? I don’t know, maybe Matthew Thies was the weather guy.

Page after page of names passed by, far too many to read or internalize. Camp & town content design. Animation production coordinators. Horse systems design. (Maybe one of them designed the horse kick that sent me flying into the mud?) Development support. Player insights & analytics. The soundtrack switched to a folk song about the hardships of life. “I’ve been living too fast, I’ve been living too wrong,” crooned the singer. “Cruel, cruel world, I’m gone.”

The credits kept rolling, and the fonts got smaller. Some pleasant instrumental music started playing. Soon came the quality assurance testers, the names of whose rank-and-file members were listed in massive blocks spread across four pages.

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-medi...ogressive,q_80,w_800/o0hrmcog0mjdm57bdb0g.mp4

Those people, 383 in all, were responsible for helping make the game as smooth and polished as it is. Many of them were employees at Rockstar’s QA offices in Lincoln, England, reportedly home to some of the most brutal overtime crunch of all. Those testers’ work, like the work of so many game developers, is invisible but no less vital. How many of them caught a gameplay bug that might have destroyed my save file and forced me to start over? Did Reece Gagan, or Jay Patel? Which of them made sure that every plant my character picked from the ground believably flopped over in his hand? Maybe that was Okechi Jones-Williams, or Emily Greaves? And which names weren’t on that list at all? Who were the people who burned out and quit, only to be cut from the credits because, per Rockstar’s stated policy, they didn’t make it across the finish line?

It is nearly impossible to answer any of those questions, just as it is impossible to assign credit for this marvelous and unusual game to any one person, or even any team of people. That’s just the way entertainment of this scale is made: vast numbers of people spread around the globe, churning for years in order to make something previously thought to be impossible. It’s a process from a different galaxy than the lone artist, sitting quietly in front of a blank easel. It has as much in common with industry as with art.

For years, Rockstar—or at least, Rockstar management—has built and maintained a reputation for being talented, successful jerks. We make great games, their posture has always defiantly communicated, so fuck off. It’s a reputation bolstered by many Rockstar products, most notably the cynical Grand Theft Auto series, with its asshole characters and nihilistic worldview. Yet how to reconcile that reputation with Red Dead Redemption 2? Could a bunch of jerks really lead the effort to create something so filled with humanity and overwhelming beauty?

View attachment 10000

“I suppose our reputation as a company was that we’re profoundly antisocial, histrionic and looking to be controversial,” Dan Houser told the New York Times in a 2012 interview promoting Grand Theft Auto V. “And we simply never saw it in that light. We saw ourselves as people who were obsessed by quality, obsessed by game design.” Of course, it is possible to be all of those things at once, and given how antisocial and willfully controversial GTA V wound up being, it was hard at the time to take Houser’s comments at face value. Taken alongside this vastly more earnest, heartfelt new game, those comments assume a slightly different cast.

Intentional or not, Red Dead Redemption 2 can be read as a meditation on failed leaders, and even as a potent critique of the internal and external cultures that Rockstar has helped perpetuate. Dutch Van der Linde is every inch the manipulative boss, frightening not only for his violent nature but for his ability to marshal people to work against their own self-interest. Time and again he reveals his shameless hypocrisy, and his promises of a new life are consistently shown to be empty maneuvering. “This isn’t a prison camp,” he says at one point, uncannily echoing every supervisor who has ever coerced an underling into a technically optional task. “I am not forcing anybody to stay. So either we’re in this together, working together to get out together, or we’re not. There simply isn’t a reality in which we do nothing and get everything.” I half-expected him to promise everyone bonuses if they hit their sales target.

The parallels between game development and gang leadership aren’t always so readily apparent, but Red Dead Redemption 2 repeatedly sets its sights on the systematic damage enabled by irresponsible leaders. It does not celebrate Dutch’s actions or his worldview; it repudiates them in no uncertain terms. Dutch is a failure and a disgrace, arguably the game’s truest villain. Thanks to the first Red Dead, we already know that he fails. We even know how he dies—not in a blaze of noble glory, but alone and cold, with no one left to stand by him. Rockstar Games, one of the most successful entertainment purveyors on the planet, will never meet the same fate, but the people who wrote their latest game sure seem aware of the risks of ambition.

View attachment 10002

Red Dead Redemption 2 is primarily a story about nature. Human nature, but also the natural world, and the catastrophic ways the two intersect. It is an often unbearably wistful homage to a long-lost era, not of human history, but of the Earth itself. It pines for a time when the wind carried only the scents of animals and cookfires, when the world was rich and its bounty seemed limitless, when the night sky was thick with stars and unmarred by light pollution. We do not live in that world, if we ever did. Every year it gets hotter; every year the storms are worse; every year it gets harder to breathe. We are careening toward ruin and no one seems able to stop us. Those with the power to lead appear too blinkered and self-interested to care.

I was moved by this video game. I was moved by its characters and their sacrifices, and by the lies I heard them tell themselves. I was moved by its exceptional artistry, and by seeing yet again what is possible when thousands of people drain their precious talent and time into the creation of something spectacular. But above all that, I was moved that so many people would come together to make such a sweeping ode to nature itself; to the wind in the leaves, the mist in the forest, and the quiet hum of the crickets at twilight.

View attachment 10001

Midway through the story, Arthur and Dutch arrive at the city of Saint Denis. “There she is, a real city,” spits Dutch. “The future.” The camera cuts away for our first look at this much-talked-about metropolis. The men have not been greeted with bright lights or theater marquees; they have been met with smokestacks, soot, and the deep groans of industry. An ominous, keening tone dominates the soundtrack. After hours spent freely riding in the open air, it is shocking.

Several hours later, I departed Saint Denis and made my return to camp. As Arthur rode, the city outskirts gradually gave way to thickening underbrush. I began to see fewer buildings, and more trees. Before long Arthur and I were once again enfolded by the forest. It was twilight, and the wind was shushing through the trees. A thick fog rolled in, and emerald leaves swirled across the path ahead. I heard rumbles through my headphones; a storm was brewing. Alone in my office, I took a deep breath. I wondered if I would ever taste air as clean as the air Arthur was breathing at that moment.

It is human nature to pursue greatness, even when that pursuit brings destruction. It is also human nature to pursue achievement as an end unto itself. Red Dead Redemption 2 is in some ways emblematic of those pursuits, and of their hollowness. The game is saying that progress is a cancer and that humanity poisons all that it touches, but it was forged at the apex of human progress. Its gee-whiz technical virtuosity has a built-in expiration date, and in ten years’ time, the cracks in its facades will be much more apparent. At unimaginable cost and with unsustainable effort, it establishes a new high-water mark that will perpetuate the entertainment industry’s relentless pursuit of more, accelerating a technological arms race that can only end at an inevitable, unfathomable breaking point.

But there is a pulse pumping through this techno-artistic marvel. This game has heart; the kind of heart that is difficult to pin down but impossible to deny. It is a wonderful story about terrible people, and a vivacious, tremendously sad tribute to nature itself. There is so much beauty and joy in this expensive, exhausting thing. Somehow that makes it even more perfect—a breathtaking eulogy for a ruined world, created by, about, and for a society that ruined it.

Oracsbox

Guest

I liked this review: https://kotaku.com/red-dead-redemption-2-the-kotaku-review-1829984369

You filthy degenerate never ever put a link to kotaku.

Burn the heretic.

sullynathan

Arcane

Pretty 4K graphics

Oracsbox

Guest

They are all 26/10 except for this one:

The original Red Dead Redemption is a fascinating, instructive point in the evolution of video game publisher Rockstar Games. As Grand Theft Auto‘s lampoon of American culture began to share space with more serious narrative aspirations and a desire for realism as great as—perhaps greater than—a desire for video game mayhem, here was a relatively straight-faced western. The story of John Marston was still visibly a Rockstar Games joint in both its concern with American decay and its detours into juvenile caricature, but it reiterated the company’s desire, demonstrated prominently in Grand Theft Auto IV, to be known as storytellers as much as provocateurs.

Red Dead Redemption 2, then, is the ambitious game Rockstar has been building toward for some time now, another relatively serious tale that gets tangled in its lofty aspirations. Marston is still around, but in this prequel he’s just another member of the ill-fated gang of the charismatic Dutch van der Linde. The protagonist this time around is Arthur Morgan, another stubbly white guy in a period-appropriate hat, albeit one of the few who seems aware that his way of life is approaching its end. The wide-open countryside gets less wide and open by the day, leaving fewer places to hide from the law and fewer places to be—as some of the characters bluntly put it—“free.”

The heart of Red Dead Redemption 2 is in the camp made by Dutch’s band of misfits, which shifts locations at different story points. This isn’t a small crew, encompassing as it does folks of different genders and ethnicities and ages who drag a few wagons’ worth of belongings behind them. Though traditional story missions come from the camp and other places like towns, these areas are most notable for the feeling of life they impart. Characters have chores and conversations and conflicts that go on independent of Arthur—and that might change to include him if he’s standing nearby.

Most significantly, Arthur can call out to and converse with any and all characters, whether they’re the named members of Dutch’s gang or townsfolk or strangers on the road. The dialogue is limited to only a few lines of being nice or being an asshole—or either escalating or defusing a situation if tempers run high—and there’s a palpable awkwardness to some of the exchanges, but they go quite a long way toward selling the all-important sense of place that the game is built on. Chatting with characters might reveal something about their anxieties or their interests, and the topic of conversation changes depending on what’s recently happened to these individuals. If, for example, two characters get into a fight and one storms off, you can hang back and say a few kind words—or further antagonize them.

Rockstar has taken the right lessons from the glut of open-world games they helped popularize, seeking to create a world that actually feels like a world rather than a collection of map icons you can choose to be guided to. There’s a focus on character and environment, a soft and refreshing restraint rather than a constant howl for your attention, that allows Red Dead Redemption 2 to stand shoulder to shoulder with the recent best of the format like The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Assassin’s Creed Origins. Arthur has plenty of ways to spend his time, but none of those diversions are constantly flashing on the map screen to beckon him over. He’s not accosted by rival gangs at every corner, and the animals he can hunt don’t trot out in front of him all the time, ready to be killed and cooked. Events like duels, bar fights, and robberies play out whether he’s engaged with them or not.

Though there are upgrades for gear and characters stats, they don’t surface in the usual way that provides you with the constant feedback of other games, where you watch bars fill and numbers climb and loot accumulate. More often than not, rewards are the experience of learning about the people and places of the game’s world. If Arthur gives a ride to characters stranded on the side of the road, they’ll tell him about themselves, maybe say something useful about the ranch over the hill. Red Dead Redemption 2‘s activities and environments blend together with a seamlessness that chips away at the hard boundaries between story missions and traditional open-world diversions; various bounty targets or gunslingers come with their own stories, while a simple hunting trip with a companion might end up just as involved as a normal mission. At its best, the game is nothing short of transportive.

For all of the significant improvements Red Dead Redemption 2 has made to an open-world template, however, it still maintains Rockstar’s bullish commitment to a clunky control scheme. Across what’s now four games and two console generations, the company’s characters have lumbered along in what’s meant to convey the weight of a real person in contrast to the light, effortless controls of so many other games. But the result is artificial rather than convincing. Studios like Naughty Dog have proven capable of giving characters a consequential sense of weight without making it a challenge to navigate around a table or requiring you to hold down buttons to move at acceptable speeds. Coupled with middling gunplay feedback and a few too many stealth segments, the chunky act of playing Red Dead Redemption 2 doesn’t feel good so much as it feels, eventually at least, tolerable.

Rockstar’s decision to cling to their antiquated movement design is especially baffling since the game isn’t shy about compromising its sense of authenticity for player convenience. As much as the game knows when to be quiet, to not drop you into one gunfight after another, Arthur noticeably arrives in the middle of each event for maximum irony and/or usefulness. The man on the road was just bitten by a snake, the train robbers have just finished unloading the passengers, and a rival gang has just opened the prison transport for their captured buddy. You rarely stumble into the aftermath of such events or arrive well before anything happens; it’s always around the height of the drama, which works against the idea of a world that appears not explicitly designed around the player. Elsewhere, you ostensibly have to monitor things like your hunger (and that of your horse), clothing relative to temperature, and the dirtiness for your guns, but these elements aren’t much more than periodic irritations rather than real commitments with an impact on play.

In other words, Red Dead Redemption 2‘s evocative, often beautiful sense of place exists insofar as it is still convenient to the player, which harms some of the desperation and hardship the game means to convey. This is best demonstrated in the bounty system, which never manages to verbalize the game’s themes about hopelessness and the recognition that you have nowhere left to run. Though your camp moves around and you’ll be wanted dead or alive in one area for a large chunk of the campaign, it’s distressingly easy to shake any bounties you accumulate by simply paying them off, as in the previous game. While this made some amount of sense for lone-wolf John Marston, it’s downright nonsensical for Arthur, who’s part of a gang on the run and supposedly looking over his shoulder every step of the way.

Though there are some intriguing systems in place to avoid becoming wanted in the first place, like covering Arthur’s face or changing his appearance, once he has a bounty, it’s a simple matter of traveling to the nearest post office to pay the $80 fine for murdering 20 lawmen and then being on your merry way. Red Dead Redemption 2 never quite squares its themes with the need to give players an open-world cowboy fantasy. And outside cutscenes and conversation, most of those themes don’t seem to exist.

Which isn’t to say that the game is particularly adept at conveying those themes in cutscenes and conversations in the first place. For as much of a pleasure as it can be to get to know some of the characters who inhabit its world, Red Dead Redemption 2 is at its worst when it tries to self-consciously make important statements. The game feels reserved and content to let the world speak for itself as you roam the beautiful vistas on horseback, but when Arthur or other characters speak about the impending death of the Old West, about the end of their era, they often sound as if the game might at any moment cut to a documentary-style talking head. This might have been tolerable if Red Dead Redemption 2 had any particular insight into the challenges faced by the people in this region of the world. It does not.

The myth of society, the inherent cruelty of people, the hypocrisy of treating predatory capitalists as a more civilized class—every warmed-over western theme is presented here without an ounce of subtlety and conveyed in the broadest possible strokes. Questioning the myth of the western is, at this point, almost as old as the base mythologizing that the genre did for so long, which leaves nothing unique to the game’s genre introspection. Red Dead Redemption 2 is the most ambitious game Rockstar has put out, in how it wants to be about something as much as the scope of its open world, but its aspirations don’t go much further than transplanting the themes of better westerns into an incredibly long video game, where you don’t ruminate on those themes so much as bump into them every once in a while on a mission.

This whole Western 101 approach unsurprisingly comes with a ham-fisted grasp of politics. A woman eventually puts on a pair of pants, one character explains white privilege and why the people in the “southern” end of the map look at him funny, another says that Native Americans were—in what is at least acknowledged as being grossly reductive—“treated poorly,” and everyone generally contemplates the horrors of racism and the aftermath of slavery. And for hours upon hours, none of this injustice is explored in any real detail.

These detours into attempted social consciousness suffer from a similarly ridiculous into-the-camera bluntness before they’re pushed to the fringes of the larger story. It often feels as if Red Dead Redemption 2 is merely parroting what’s expected to be said when portraying such things, to show that the game at least recognizes what it’s portraying, so that it may sufficiently get away with rendering a town where the black folks live on the outskirts or having one character accuse another of fucking slaves. Prejudice is given no more focus than as period-appropriate flavor, a patronizing tourism meant most of all to inform the myth of the white outlaw in a hypocritical society; at one point, Arthur makes a laughable statement to some Native American characters that goes something like, “The government don’t like me any more than they like you, and like you, my time here is nearly finished.” After all, if the white outlaw can no longer be free, then who truly is?

What the game’s acknowledgement of these struggles does most of all, though, is make Arthur and his problems feel small by comparison. He’s not a terrible character. In fact, there’s a certain charm to his exasperation with everything, and it’s interesting how he’s resigned about who he is as someone who’s not made for any other line of work. But he’s weaker for being in the vicinity of a player-character blank slate, whose outfits, facial hair, and haircut may be changed. He seems written mainly as a snarky mouthpiece for the game’s well-worn themes, as if they aren’t explicitly conveyed elsewhere. Like Red Dead Redemption 2 itself, he looks the part and can even be enjoyable, but there’s distressingly little going on beneath the surface. For as adept as Rockstar is at placing you within a wonderful, lavish world and letting you move within it, they’re still figuring out how to say all that much about it.

https://www.slantmagazine.com/games/review/red-dead-redemption-2

I was worried this might be the case.I've never been enamoured by the clunky controls of rockstar games and it seems that's not changed.The addition of unrealistic modern views on stuff I expected, the first RDR had it as well and felt just as out of place.No outlaw would give two shits about Indians,women's rights or wogs.

Why even have the character as an outlaw ! If their going to constantly be moralizing yet at the same have all these opportunities to go ape shit don't have a conflicted criminal as the central character.Either have a good guy and don't have the criminal activities or go full outlaw and not bitch when I play like one.

Putting in all these realistic mechanisms for eating,bathing,horse balls,shitting,fishing etc... are nullified if the overall game systems are retarded like paying off cheap bounties for mass murder.

SpoilVictor

Educated

So it is good or bad?

And if is so good it is as good as GTA V which got 10/10 GOTY IGN Would play again all over the world (and turned out to be utter shieet)?

I shall see in 4 years (1year waiting for PC release + 3 years wait for decent sale).

And if is so good it is as good as GTA V which got 10/10 GOTY IGN Would play again all over the world (and turned out to be utter shieet)?

I shall see in 4 years (1year waiting for PC release + 3 years wait for decent sale).

So it is good or bad?

Looks like a fantastic interactive movie. Great fun to watch, total BSB to play.

Therefore an ideal entertainment for long winter evenings, watching my favourite mass-taste Youtuber Fightincowboy.

Life of the Party

Arcane

- Joined

- May 8, 2018

- Messages

- 3,535

Makabb

Arcane

- Joined

- Sep 19, 2014

- Messages

- 11,753

https://www.metacritic.com/game/playstation-4/red-dead-redemption-2

Never seen so many 100's on metacritic, 'best open world game of all time and one of the best video games ever' is citated often

Never seen so many 100's on metacritic, 'best open world game of all time and one of the best video games ever' is citated often

unfairlight

Self-Ejected

- Joined

- Aug 20, 2017

- Messages

- 4,092

I've never seen so many 100s on metacritic before the last 'best open world game of all time and one of the best video games ever' released a year ago, Breath of the Wild, and the other best video game ever released 3 years ago, The Witcher 3.

Last edited:

Life of the Party

Arcane

- Joined

- May 8, 2018

- Messages

- 3,535

10 – Criticisms often come easier than compliments, but in the case of Red Dead Redemption 2, I am at a loss. This is one of the most gorgeous, seamless, rootinest, tootinest games ever made, and if you voluntarily miss out on it, you’re either not a gamer or in a coma.

The Good – If I have to choose only one, it has to be the sheer amount of detail packed into its game world.

The Bad – I would say the odd graphical glitch if they weren’t more humorous than annoying.

The Ugly – I may have considered uninstalling the game when I lost my horse Cobalt…

There are approximately five moments in my personal history of gaming that are permanently burned into my memory, and two of them are from the first Red Dead Redemption. One was the moment I crossed into Mexico for the first time, with Jose Gonzalez’s “Far Away” setting the mood. The second was a little less refined, involving a bandit inadvertently shooting himself in the nethers. Obviously, the tone of these experiences differed, but their impact was the same. Red Dead Redemption gripped me in a way few other games ever have. All this is to say that my expectations for a game have never been higher than they were when I started Red Dead Redemption 2. With each passing chapter, I expected to find something that would dip the game below the high bar I set for it, and when the game ended, I was still left waiting.

While Red Dead Redemption 2 starts out safe by connecting its story and region to that of the first game, the prequel’s emphasis on lush environments like forests, grasslands, and swamps—rather than the arid biomes commonly associated with Western dramas—was initially a bit of a shock for me. I struggled to imagine a cowboy setting without an ample supply of sand and tumbleweeds, but while such settings do get their time to shine, wholly mimicking the last game’s environments would have done the prequel a creative disservice. The new environments still effectively cater to the general Western theme while offering new opportunities for the series to evolve both aesthetically and mechanically. It also doesn’t hurt that Red Dead 2’s map is made up of the most beautiful landscapes I have ever explored in a video game, bar none.

What makes a game “good looking” generally equates to either hyperrealism or striking artistry, but Red Dead 2 manages to split the difference. The balance between the technology and art that makes up the game’s setting goes beyond the visual appeal, as nearly everything in its environments is physicalized and reactive. From leaves falling and branches bending as you pass through bushes to snow and mud deforming under your feet, the density of detail gives an impression of teeming life. The world’s lighting and colors also do it some great favors, giving the entire presentation a dry crispness that can’t be fully appreciated without seeing it firsthand. This visual design would impress layered over one small town, but the actual scale at which it can be appreciated defies reason. Red Dead 2’s map pushes industry boundaries in both size and detail, and players will find its world to be even bigger than it initially appears.

Players explore this world as Arthur Morgan, a lieutenant of the Van der Linde gang that John Marston mopped up in the previous installment. As Red Dead 2 is set before the events of the first game, we meet Arthur at the peak of the gang’s infamy, with local law, the government, and rival gangs closing in from all sides. Things go from bad to worse for the gang throughout the adventure, and while Arthur always strives to be the voice of reason, he is far from being a blameless hero of virtue.

There are several instances in which I’d argue that Arthur’s actions—by his own volition in cutscenes, not my command—make him a genuinely bad person. Rather than alienating me from the character, however, these sins heightened my sympathy for Arthur. There’s an identifiable shift in the character’s world view over the course of the story that would lack the same impact if he didn’t start out as a ne’er-do-well with a circumstantial conscience. The theme of Marston’s redemption in the first game was determinedly unmistakable, and yet Arthur’s more subtle journey of redemption seems far more redeeming than his counterpart’s.

The members of the gang that join Arthur on this adventure, while lacking the same face time, feel just as human as the protagonist. When not fighting at his side, these characters live in the gang’s constantly relocating camp, which Arthur is instrumental in supporting. Money and resources collected while playing can be contributed to the camp, providing the opportunity to upgrade it in a variety of ways. Watching the camp grow serves as a pronounced and interactive metric of one’s progress. And not only do these upgrades confer gameplay advantages—primarily in the form of excess supplies—they also lift the mood of the camp’s residents, which comes across in the game’s extensive conversations.

Red Dead 2’s conversation function is practically simple but systemically fascinating. Holding left trigger next to an NPC—whether it be a camp resident, stranger, or even a friendly dog—opens up the available conversation options for that character, and navigating these options effectively is just as useful as lining up a gun barrel. Outside of objective-based scenarios, most options involve either greeting or antagonizing a person, with prompts for robbing, threatening, or defusing a target also regularly popping up, depending on the situation. It can even be used to talk your way out of arrest, should you not be in a killing mood that moment.

Beyond the adaptive nature of this tool, the resulting conversation topics are astounding. Characters remember favors you’ve done for them, or ways you’ve wronged them, and bring these up in conversation. When talking with gangmates, they’ll address current events in the camp or recent decisions you’ve made, while new faces on the open road may only give you a simple “howdy.” The network of branching possibilities is smaller than some other games, but the conversations themselves are infinitely more organic.

Fortunately for players and unfortunately for those who die, problems can’t always be solved with words, and guns will be drawn more often than not. Red Dead 2 falls back on Rockstar’s tried and tested third-person, cover-based gunplay, but something unique (at least to my knowledge) is shaking up this combat convention. Most firearms must be manually hammered back between each shot when aiming, either by pulling the right trigger again, or by lightly tapping the aim button. This may sound insignificant, but it injects a split-second delay into the rhythm of firing, which can make the difference between landing a shot or splitting air.

Lining up these shots is fairly stiff, but a quick tap of the aim button to rechamber a round also reorients the game’s generous aim assist, killing two bandits with one slug (that’s how that idiom goes, right?). Once you’ve acclimated to this process, and also accepted the viability of popping and shooting over running and gunning, it makes for an interesting challenge without being a frustrating obstacle. Few games attempt to reinvent the point-gun-pull-trigger quintessence of shooters, but Red Dead 2 achieves it with confidence and grace. Although, be warned, trying to optimally dual-wield two weapons with different bullet counts and firing rates is like playing Dance Dance Revolution with your fingers.

Another caveat gunslingers must be wary of is that not all weapons may be ready for every fight. Firearms can degrade from overuse and exposure to elements, lowering their stats, so they need to be regularly maintained. Alternatively, some of the game’s situational armaments like the silent bow, non-lethal lasso, and various melee weapons don’t have the same condition, so it’s important to always consider what tools you’re carrying. There is only space for two side-arms and two primary weapons on your person, with your remaining firearms stored on your horse. Restricting the player’s loadout, like manual weapon hammering, is a limitation that actually benefits the experience of Red Dead 2. When every option is available at all times, it’s easy to fall into a stagnant groove of your favorites. This new system encourages consideration of what weapons best suit the task at hand, which is more likely to result in trying new things.

Different weapons have different optimal situations, but every situation benefits from using the Dead Eye skill, back and better than ever in Red Dead Redemption 2. Just like the previous game, players can enter Dead Eye to temporarily slow down the world and paint targets before rattling off impeccably accurate shots in quick succession. The ability evolves as the player progresses through the game, unlocking new features such as a highlight for vital body parts on enemies. Dead Eye is the most epic slow-motion ability in the business, and it’s also an extremely useful tool when you find yourself in particularly harrowing gun fights.

To ensure Dead Eye doesn’t run out in the middle of a firefight, players will want to keep a living eye on the ability’s Core. Arthur has three Core stats that must be maintained—Health, Stamina, and Dead Eye—each with a meter surrounding its Core reserve. Burning through a stat makes its respective meter go down, while its Core amount depletes over time, as a last-resort reserve for the meter, or through other means. The lower a Core, the less efficiently its meter recharges, but Cores can be replenished with various consumable resources like food provisions and alcohol. Core management, while starting out as a bit of a nuisance, quickly becomes habitual and makes for an intriguing survival element without quite the same pressure of imposing death. It’s demanding enough to engage but simple enough that it doesn’t drag down one’s adventuring. Plus, the system gives value to resources that largely fell by the wayside in the previous game, where its comparable stats required no long-term maintenance.

Arthur isn’t the only character with Cores that need looking after. The player’s horse also needs its stats maintained, which one should do diligently, as these creatures are no longer the disposable tools they were in the last game. Players build a bond with their horse through actions like feeding it, brushing it, and riding it. The greater the bond, the tougher and braver the beast becomes, while also unlocking new moves for it, such as the equestrian version of drifting. Horses can no longer be called from anywhere, but a greater bond also increases the distance at which it can be summoned. This redesign trades convenience for sustainability, but more importantly, it makes the horse into as much a supporting character as anyone in the gang. Losing a horse means it’s gone forever, and even if that doesn’t crush your heart, the time and money you’ve invested into it will still leave you reeling. If you have a soul, though, the emotional connection is unavoidable. I’ll never forget you, Cobalt.

Much of the bond between player and horse is generated through the long treks between missions. Should the breathtaking landscapes not do it for you, and the extended travel time feel a little dull, there are a couple fast-travel options, but taking these means missing out on some of the game’s best content. During normal travel, players will frequently come across random events, which can manifest as anything from saving a kidnap victim to simply helping a vagabond with a few coins. Grateful recipients often reward the kindness with either helpful resources or useful information that leads to new experiences you may not have discovered on your own.

The step up from random events are the Stranger missions—side quests that highlight some of the frontier’s colorful personalities—with story missions topping it all off. Activities found in missions, story or otherwise, can range from tranquilly menial to frenetically action-packed, each excellently juxtaposing the other. Red Dead Redemption 2’s most memorable moments are shared between these peaks, with the former building relationships between the story’s best characters, and the latter hosting all the Wild West set pieces you could ask for, from robbing trains to breaking out of prisons and beyond. When it’s time to just kick back, players can hunt wild beasts, play a round of cards, stir up trouble with random townsfolk, and so much more. The game’s array of available activities is extensive to the point of being almost overwhelming.

Your actions during these activities and missions will dictate your Honor level, which is increased through benevolence and decreased through violent impulsiveness (specifically toward those who don’t deserve it). A high Honor level translates to discounts at shops and being more agreeable in conversation, so while baseless aggression is satisfying, it does pay to play nice. Fortunately, Honor works on a long spectrum, meaning you can get away with a few misdeeds without jeopardizing too much of your wholesome reputation, or vice versa. It’s a simple system that fits the outlaw vigilante theme and gives consequence to decisions beyond their immediate payoff.

Action and drama are helpful in building a story, but subtle details—like those drawn out by the game’s Honor system—are what make a world. The uneasy glances you get from passersby with your weapon drawn, the way your horse gets skittish around predators, or even something as simple as guns fitting perfectly on your back without clipping through your outfit- these efforts are vital for immersion, as they purge from the world that which would form schisms between players and the experience. This immersion can be even more enhanced with the game’s first-person mode, should players wish to experience Arthur’s story from behind his eyes. The game was definitely built with third-person in mind, but the first-person mode is no hack job, making yet another case for the exhaustive care and attention that went into this game.

In this industry, there are generally two schools of thought for what constitutes giving a game a perfect score: it’s an experience that shouldn’t be missed under any circumstances, or there is nothing about the experience that needs changing. I lean toward the latter myself, but regardless of which you subscribe to, Red Dead Redemption 2 earns the mark. From the moment in the intro where I noticed Arthur slightly puts his hand up toward cold wind, to the stellar end-game payoff that won’t be spoiled here, nothing during my adventure into Rockstar’s newest frontier failed to delight. High expectations are always a recipe for great disappointment, but how foolish I was to ever doubt Red Dead Redemption 2.

http://www.egmnow.com/articles/reviews/red-dead-redemption-2-review/

Pretty much the way I feel when playing grossly overleveled Geralt in Witcher 3 then.So it is good or bad?

Looks like a fantastic interactive movie. Great fun to watch, total BSB to play.

Therefore an ideal entertainment for long winter evenings, watching my favourite mass-taste Youtuber Fightincowboy.

I know a guy who is a 3D artist and had to spend 3 months making nothing but swords and shields for a TW title."so what do you do?"

"i'm lead vegetation design-- hey, wait!"

Yep, it's a full-blown interactive movie. Damn mighty impressive and a technical marvel, that's for sure. And I'm sure the world will open up after the tutorial. But I don't see this game having anything more than ZERO replayability.

Frusciante

Cipher

- Joined

- Aug 24, 2012

- Messages

- 716

You can say what you want but game is already very atmospheric and has a great western vibe (I'm still in the first hour or so). Graphics are amazing as well.

As for replayability, not sure why anyone would replay a 100+ hour single player game anyway - but then I never replay games (except strategy games of course).

As for replayability, not sure why anyone would replay a 100+ hour single player game anyway - but then I never replay games (except strategy games of course).

Life of the Party

Arcane

- Joined

- May 8, 2018

- Messages

- 3,535

If you're looking for a Wild West game there's something much better than this.

- A Unique “Weird” West World: Explore a world where Western legends meet demons, arcane rituals and satanic cults and where the dead can walk the Earth again. For a price.

- Compelling Turn-based Combat: Control 1-4 squad members in thrilling turn-based combat encounters and master a range of powerful western-inspired special abilities, from feats of gunslinging to survivability against all odds, to take out your opponents in a series of original tactical maps with unique story-based objectives.

- Collect and Combine Special Abilities: Obtain new special abilities by collecting and equipping unique cards which are earned throughout the game by completing main- and optional objectives, exploration , bartering, treasure hunting and more. These cards can be combined to create even more powerful combos, and provide additional options in combat.

- Choice and Fate: Experience a deep story where decisions made during and between combat scenarios will resonate through future events and change the ultimate fates of a divisive group of colorful characters

- Luck of the Draw: Use a combat system that goes far beyond pure probability by featuring luck as a unique guardian of engaging and challenging combat

- Dynamic Cover: Change the flow of combat thanks to an extensive cover system which allows for the creation of effective cover from objects in the environment, making flanking and maneuvering during battles a truly powerful tactic

- Shadow Spotting: Exploit the Blazing western sun to Locate out of sight enemies by the shadows that they cast, along with the sounds they make

- Ricochets: Utilize Metal objects to allow master gunslingers to shoot beyond the line of sight for increased tactical combat options, and diversified planning

- 40 Historically Inspired Weapons: Equip and employ an eclectic collection of deadly shotguns, rifles, pistols and sniper rifles, all based upon real outlandish prototypes, designs and ideas from the era

- Joined

- May 25, 2006

- Messages

- 8,363

Yes comrade, selling a product for money is the epitome of evil. Crush capitalism!Rockstar doesn't deserve your money. Their shady business practices are as bad as EA or Ubisoft.

I can't understand why they "simulated" the game this much. Walking/running animations seems really slow and looting dead bodies after a long fight takes longer than fight itself...

Salvo

Arcane

- Joined

- Mar 6, 2017

- Messages

- 1,414

Yes comrade, selling a product for money is the epitome of evil. Crush capitalism!Rockstar doesn't deserve your money. Their shady business practices are as bad as EA or Ubisoft.

Quite the hyperbole you have there. I simply do not support Rockstar's predatory actions, or rather their publisher's, Take-Two, such as promising single-player expansions and then focusing on multiplayer instead, aggressive microtransactions, re-releasing the same game under the guise of a different edition, willngly holding out on the PC version for years to force those interested into buying the console one, and more.