-

Welcome to rpgcodex.net, a site dedicated to discussing computer based role-playing games in a free and open fashion. We're less strict than other forums, but please refer to the rules.

"This message is awaiting moderator approval": All new users must pass through our moderation queue before they will be able to post normally. Until your account has "passed" your posts will only be visible to yourself (and moderators) until they are approved. Give us a week to get around to approving / deleting / ignoring your mundane opinion on crap before hassling us about it. Once you have passed the moderation period (think of it as a test), you will be able to post normally, just like all the other retards.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Arkane PREY - Arkane's immersive coffee cup transformation sim - now with Mooncrash roguelike mode DLC

- Thread starter LESS T_T

- Start date

ciox

Liturgist

- Joined

- Feb 9, 2016

- Messages

- 1,405

So the only platform that really needs a demo is not getting it.

Console-only or console-first demos are a time-honored tradition of immersive sims.

http://bioshock.wikia.com/wiki/BioShock_Demo

- Joined

- Apr 12, 2011

- Messages

- 369

I missed this one:

Some nice new footage.

Some nice new footage.

http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2017-04-12-arkanes-living-prisons

Arkane's living prisons

Raphael Colantonio on Prey, Dishonored and breaking the world.

By Edwin Evans-Thirlwell Published 13/04/2017

Arkane Studios is known as the developer of "immersive simulations" - worlds you sink into, wallow in, made up of intricately interlocking systems tied to exotic abilities, which can be manipulated to resolve a scenario any number of ways. But perhaps it would be more accurate to describe the Lyon and Austin-based company's creations as "emersive" sims, frameworks you struggle to break free of, using tools that aren't quite under the designer's control.

Just look at how they generally begin. Every Arkane title to date save for third-party licensed spin-off, Dark Messiah of Might and Magic, has opened with the player character in captivity - from the dingy jailhouse of the studio's 2002 debut Arx Fatalis to Emily's sealed bedchamber in Dishonored 2. It sets a certain tone, and while the Dishonored games ultimately cast you as a free-wheeling renegade, a rogue cell in the body politic, their stories and sandboxes are tainted by the knowledge that even the most open-ended piece of design is necessarily a form of entrapment, a set of cues and goads that insensibly guide or repel.

Arkane's well-regarded but underselling Arx Fatalis was pitched as an Ultima Underworld sequel, but the studio didn't want to yield control to prospective publisher EA.

The streets of Dunwall and Karnaca may reward curiosity in ways a Call of Duty game never would, but they are still masses of baked-in vectors and scripted solutions, with lighted windows that tug at your attention, collectibles that lure you into the mouths of alleyways, villains whose various downfalls are woven into the terrain, waiting to be excavated. The real challenge of a game like Dishonored 2 - a challenge that informs every bit of developer discussion of its mechanics and variables - is accordingly to discover something, some tactic or access point, that Arkane hasn't anticipated. This is made explicit in the game's legendary Clockwork Mansion, a tacit interactive design essay in which your adversary is essentially a malevolent level designer, tracking your route through his collapsing, reassembling laboratory much as publishers amass telemetry on player behaviour, till you slip the clutches of the critical path and turn the stage machinery against him.

"I think everybody likes to see what's on the other side of the décor," observes Raphaël Colantonio, Arkane's co-founder and president. "People like to go outside the boundaries, otherwise it just feels like 'oh, I know what you want me to do, game designer'. But as long as you can - not break the game in a way that is not fun, but break it in a way where you're like, 'oh, the game is still going, but I'm doing something that [wasn't planned for].' I feel special right now, because I'm doing something that is not planned - I think that's a great feeling for players."

In many ways, of course, the Clockwork Mansion is the greatest feat of deception of all - it sells the fantasy of liberating yourself, toppling the creator, within what is nonetheless an exquisitely choreographed and controlling piece of design. Eminently hateable though he is, the sociopathic Kirin Jindosh is little more than a consolatory metaphor, a prancing puppet-master to distract you from who is really pulling your strings. But if Arkane's gilded prisons are unbreakable, they are animated by a radical sensibility that is poorly served by critical paeans to "detail" or the mere quantity of meaningful choices a scenario supports.

If games are teaching mechanisms, Arkane's games teach you to distrust your teacher, to overthrow structures ostensibly put in place to aid or entertain. Much as the Dishonored games tell tales about the abuse of political power, so their levels are crucibles for activist tendencies that have a wider utility, to say the least. It's not just that they shatter the fourth wall, that much-abused grab for sophistication in fiction, or that they present you with landscapes that admit of more invention than in many games - it's that they reveal themselves for instruments of incarceration and encourage you, with varying degrees of gentleness, to break your restraints. Perhaps I'm going too far, but if I wanted to teach a course about institutions of oppression and methods of revolt as manifest in popular culture, I know which video games I'd bring to class.

The Clockwork Mansion is probably Dishonored 2's finest level, not least for the realisation that there are an additional set of environments just down the hill from its door.

Designing them involves no small expense and, as Liam Neeson would say, a very particular set of skills. "They're hard to make," says Colantonio. "There are a lot of invisible values in them, problems that people don't like to solve. All the possibilities - it's more about fixing a million problems than doing content. If you look at the effort that is poured into doing things to make it work, where if you were making some other kind of game you would not have to worry about it - what if the player does that? What if the player does this?

"Other games don't care about that and they get away with it, so I guess that might be one reason why people don't make these games so much. And secondly, I think they're hard to sell. I don't think publishers, other than Bethesda who really understand us because they've had their own success with this sort of game - I remember working with other publishers, and most of those values that are very inherent to immersive sims, most publishers are like: 'Why would you worry about that? Why do you care? What's the value? How does it sell the game?' I guess that's why they're rare."

It isn't just the moneymen who may fail to see the point of an immersive sim. Team members may take some convincing, even given a fondness for Arkane's previous work. "You definitely need a special kind of team," says Colantonio. "You need people who will trust you, because often they also go 'why do we waste time doing these kinds of things', or 'are you sure this is a good idea', and then eventually [they understand].

"We've had that in every game - when we recruit more people, some of them are really ready for this kind of game, but most of them they're not, so we have to tell them that you're going to do things that sometimes you'll have to redo, sometimes we'll throw them away. Some people are fine with that, and others find it too hard. And then at some point, those people realise that what they were actually working on, when it comes together - they realise why we do all this."

Where The Clockwork Mansion is like pitting your wits against a level designer in real-time, the subsequent Crack in the Slab inverts one of Dishonored's core concepts, the practice of shaping an area's destiny. Here, the level is already in an 'endgame' state, and you're asked to rewrite it.

From Dunwall to Dunmer

Colantonio isn't averse to the idea of tackling another of Bethesda's big licenses, though he'd rather create universes than take charge of an existing one. "I love The Elder Scrolls, I love Fallout - those resonate very much with my sensibilities. Those I would, and it's also - those have a lot of depth and a lot of systems, so it's kind of in my area of what I know how to do, what I enjoy personally. So that would work out." It's an intriguing prospect - Arkane is as fond of incidental clutter and spontaneously interacting systems as Bethesda, and there are aspects of Elder Scrolls fiction in particular that seem well-suited. I'd love to play an Arkane game set inside one of Tamriel's more memorable cities, such as Vivec City on the isle of Vvardenfell or Solitude in Skyrim.

Integral to the development of an Arkane game is letting ideas for player abilities grow without respect for balance, allowing them to warp the structure of the game around them - Dishonored's Blink power, a teleport-dash which was originally one of the game's unlockables rather than a ubiquitous base ability, is a good example. Also integral to the development of an Arkane game is knowing when to stop, knowing when a system or tool is beginning to overwhelm the rest.

"I would say every game we've had problems like that," comments Colantonio. "I could go all the way back to Dark Messiah, with spawning frozen puddles on the floor and having people slipping on them, which was fun at first but then it would create situations where it just became ridiculous. We've had that all along.

"To find an example in one of the more recent games, Dishonored has a good one where by doing a double-jump plus a Blink, maybe combined with Agility, you could traverse a huge amount of space. We didn't really limit that - well, we did to some degree, we capped the momentum that you could aggregate, but we left it at a high value because we thought, 'eh, why not?' If somebody finds a way to access somewhere we didn't plan for, it's kind of cool, as long as it doesn't just break the game."

Arkane introduced a new generation to the concept of immersive simulation with the first Dishonored, reportedly exceeding internal expectations by a significant margin, though the sequel appears to have attracted fewer buyers for all its rapturous reception. The developer has also become more central to parent company ZeniMax Media's operations, taking on the Prey license after ZeniMax and publisher Bethesda fell out with original developer Human Head.

Arkane's re-interpretation of Prey began life in 2014 as a new IP, loosely inspired by the inter-connected dungeon of Arx Fatalis - set in 2032, it sees you touring a retrofuturist space station overrun by a range of formless aliens, including scuttling "mimics", reminiscent of Half-Life's headcrabs, that can assume the form of inanimate objects. It's a signature twist because it brings Arkane's taste for sumptuous, evocative period decor into conflict with its knack for systemic volatility - that faux-60s lampshade you're studying could be a mimic waiting to wrap its legs around your head.

Prey's Gloo Cannon petrifies attackers, but can also be used to create platforms and block terrain hazards. There are doubtless many undiscovered applications.

"We don't decide what object they turn into, except at the very beginning of the game, because we want to introduce the mechanic to the player," notes Colantonio. "But at some point [in each area], there's an object that might be or might not be a mimic, and if a mimic is fighting you and escapes around a corner, it has a chance to turn into something. So if I play it and then you play the same area, it might not turn into the same object each time."

"We do set up some moments to fool the player - for example, put two of the same object somewhere, so that player might think 'ah, there are two trash cans, so maybe one is a mimic'. We do a little bit of that, but most of the time we just leave it to the simulation, and let the game do its thing."

Arkane doesn't stop there, however - over time the player will also acquire the ability to transform into (supernaturally and somewhat hilariously mobile) objects, a power that, as with those Blink combos, threw other parts of the game out of whack. "That was more of a nightmare for us, because if you're too small, you can fit into spaces, maybe access places we don't want you to access. So we've had some tuning to do there, defining how small an object we can accept the player to be, versus how big an object we can accept, and we've come up with some rules that feel consistent and fair."

I checked out a demo build of Prey shortly after speaking to Colantonio, and was immediately gripped, not least by the developer's ambivalent allusions to its prior work and the style of game it has kept alive. Buried in one email you'll find mention of Looking Glass Studios, the company behind the first Ultima and Thief games - foundation stones of the immersive sim genre that were an enormous influence on Colantonio and Arkane's co-owner Harvey Smith, in the days before they worked together. The reference is more than an in-joke, I think. The in-game email chain in question concerns a part of the station that is essentially a glorified themepark ride - a positioning of Arkane's heritage within the new game's fiction that is difficult to read, but which I take for a reminder that every simulation, however lavish in its spread of possibilities, is another clockwork mansion at heart.

There's also a make of spanner named after Hephaestus, Greek god of artisans and craftsmanship - an ironic association for a tool that will serve you mostly as a bludgeoning implement. As with Arkane worlds in general, there's a gentle provocation here, the suggestion that you might be able to do more with what you're given than is immediately apparent. Providing you have the imagination, of course, but more importantly, providing you actually want to be free.

https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2017/04/13/prey-alien-powers/

Do alien powers make Prey more than another sci-fi shooter?

By Alec Meer on April 13th, 2017 at 3:00 pm.

A few weeks ago, I played through the first section of Bethesda and Arkane’s upcoming first-person-shooterbut Prey [official site] (no relation, other than in name, to the original Prey or its aborted sequel). I like it well enough, particularly the Total Recallish sense of intrigue it raised about what was really going on and whether the player-character was the person they believed themselves to be. At the same time, I’m not sure how much I truly had to say about it, outside of description.

It was there, polished and pacey, absolutely the kind of thing I traditionally enjoy in an action game – but it was guns and monsters and doorcodes. Where was the thing that made Prey unique? I’ve been back and played a later section of the game, amongst other things I’ve transformed myself into a stack of towels and now I have a much clearer sense of what this new Prey really is. I can show as well as tell you why.

The thing that we all got hot under the collar about when real details of Arkane’s Prey reboot began to trickle out was the option for alien-derived powers, in addition to gunplay and Deus Exy hacking/strength/stealth abilities. Turn into a cup! Yeah, man. I’m down for that. That the idea of roleplaying as an inanimate object while playing an exciting action game is what most appeals probably says far more about me than I am comfortable with. Regardless of whatever unhealthy interest in kitchenware I might possess, it was a mild disappointment that my first hands-on encounter with Prey had all the alien stuff locked away.

The new section I played is, in terms of the game’s internal chronology, about 45 minutes on from where the first chunk left off. I’ll dodge story stuff, of which there was in any case less, this time around, and focus on features. Features like this:

The absence of floppy cloth physics is mildly heartbreaking, but even so: I can roam around an alien-infested space station in the future while pretending to be a stack of towels. Dishonored has rats and fish, but not towels. I’m a fluffy, 100% cotton master of stealth. And I’m particularly tickled that I did this while Benedict Wong wittered exposition at me. I’m taking this seriously, bro, honest.

Three major questions are raised by the transformation power. One, how generous is the game about what you can turn into? Well, it’s hit and miss, I found. There’ll invariably be at least one object within sight range at any one time, but at the same time you’ll spend some time fruitlessly waving your cursor over a lot of stuff, gradually learning about what is and isn’t allowed. Transform power upgrades theoretically open up the options further, but I wasn’t able to shove enough points into unlocking that during my hour or so with the game. For tier one transform, generally speaking it’s small, light objects – the biggest thing I Optimused into was a desk chair. Speaking of which, let me demonstrate the answer to my second question, which is ‘could you, in theory, play through the entire game as a random object?’

As you can see, I’m able to rattle around the floor without issue, even performing small hops to climb up stairs, but catching a space elevator to the next floor reverts me back into bipedal form. Prey offers various routes around its levels, so possibly in that instance there’d be a way to progress without become dechairified, but the majority of those other routes involve being human so I can hack or repair or fire rubber arrows at switches from afar or build custom staircases with my glue gun.

The third question is ‘what about combat?’ Tragically, as a chair I’m not able to pummel foes with my aluminium legs, or try to suffocate them by wrapping my towel-form around wherever I approximate their noses to be, but there is scope to use transformation for stealth-based purposes.

Now, in my short time with the game, I can’t say that I encountered any situation in which avoiding combat was at all necessary, and nor was there any story-based reason to leave Typhon – the collective name for the various types of murder-tarball aliens-or-are-they in the game – alone. However, I can well imagine that ammo shortages and larger enemy numbers and/or more dangerous variants later in the game might change that – plus I have good reason to believe that I’ll end up facing humans as well as monsters, in which case my killer instincts may well be dulled for moral reasons.

In any case, stealth while transformed does not permit sneaking. The Typhon I was up against are not stupid, and will spring into lethal action if they see a cardboard box creeping along the floor, like so:

Transformo-stealth is going to be more of a waiting game, either hoping enemies will leave the scene or that they’ll wander into range so you can ambush them. Given the aforementioned presence of some NPC humans, I wonder if we might be in for a spot of Assassin’s Creed-style tailing people and listening in on conversations too, though all this is merely speculation for now. A stealth element I’m more confident will come into play is body-morphing in order to avoid security systems such as turrets.

While these things are ostensibly on your side – i.e. they’re there to protect the station from Typhon – the trouble is that sticking too many alien modifications into your brain makes them read you as being alien too. So you have a choice to make – an easier life but no towelling, or access to the game’s most playful powers but a harder time getting around the place.

If you do go for the latter approach, and I’m reasonably sure that anyone with an ounce of joy in their soul will, the good news is that the mimic power isn’t purely about avoidance or homeware cosplay. It can also be used to access places that are otherwise out-of-bounds. For instance:

I have to make a confession here. I did not make that connection without prompting from a nearby Bethesda bod. Which speaks to my lack of ingenuity as much as it does that, hopefully, Prey isn’t being too obvious about things. It’s shooting for a sci-fi place that feels plausible, not one full of ‘yoo-hoo!’ giveaways like mansize vents and doorcodes scrawled on the floor in bits of lower intestine. Of course, I can only speak to what I saw in an hour-long chunk of the game, however.

Another example of that sort of thing is breaking into a locked morgue. I spent ages scouring the ceiling for ventilation shafts before finally finding a use for a dartgun that had thus far proven entirely useless in combat:

So yes, in some respects this is more of a sci-fi remix of Dishonored than I’d thought it was in my first play session. Nowt wrong with that, quite the opposite in fact. I didn’t click with Dishonored 2 to the extent many people (rightfully) did, purely because the setting and structure felt a little too similar to Dishonored 1’s.

The idea of transplanting the same ethos into a very different environment, with very different powers and foes, appeals that much more. At the same time, it doesn’t feel like Dishonored – this is more like the haunted spaces of Bio- and System Shock than the living cities of its stablemate or its other key touchstone, Deus Ex.

That said, as I’ve previously alluded to, it’s not a complete ghost town. Various apparently friendly NPCs chat to you via radio, in what I’m afraid was pretty much exclusively exposition during this segment, hovering helper bots will restore your health and armour and, occasionally, you might encounter a test subject. I ran into a convicted criminal, locked in a glass cage by the TranStar corporation (who protagonist Morgan Yu works for), into which a Typhon can be released in order to monitor the combination of assault and mimicry that follows.

Only that hasn’t happened yet, because the station got abandoned when other Typhon got loose. So it’s up to you. You can read his rapsheet on a terminal nearby, and decide whether you believe his protestations of trumped-up charges, or decree that he’s scum of the earth and deserves to be torn apart by fractal slime. Or you can strike a deal with him. I happened to encounter him after I’d found my way into the armoury by sneaking through its letterbox (as seen in the fourth video above), but had I not, he could have told me another way in.

As you can see, I set him free anyway. Of course I did.

I should mention that the game didn’t seem entirely sure what to do with him thereafter – he just sort of hung around – which was a shame, and not for the first time makes me understand why BioShock didn’t let you meet sane characters face to face, but I like the idea that this is still a living space, not just a haunted house. Fleeting choices that build up who you are as a person, not just what kind of killer you are. I suspect Mr Ingram above will crop up in some capacity later in the game, however, given that he’s voiced by Walton Goggins (that guy with infinite teeth from The Shield, Justified and the last couple of Tarantinos).

The best thing, though, was that I had a character screen full of powers I’m yet to experience. From the more traditionally Deus Exy, such as hacking and heavy lifting, to more alien fare such as telekinetic blasts and time-slowing – nothing else as a transformative as transformation, at least not that I could see, but it’s all about these things in combination.

Powers are dual-wielded with weapons, BioShock 2/Infinite-style, and many of the weapons function more as a tool than a killing device. The gloo gun that locks Typhon in place, a silenced pistol, a zap-ray for humans (not that I’ve encountered any enemies of that type as yet), that rubber dart gun you saw earlier, a gravity mine that pulls everything not nailed down towards it… Yes, there’s a shotgun too, but it almost feels like that’s there as a shrug: “well, if you must have a standard weapon, here you go – but look at all these toys!” Lots of combinations, both in terms of combat and in terms of navigation.

That’s Prey, then. Not just a game about finding a way around a space station, but perhaps one that’s far more meaningfully about creating your way around it. While pretending to be laundry, ideally.

This game will fucking rule. Bethesda haters gonna hate and all that.

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2011

- Messages

- 99,690

Some PC gameplay in some french preview:

I'm not watching anymore videos. Too spoilery.

Latelistener

Arcane

- Joined

- May 25, 2016

- Messages

- 2,625

Is there a chance that you will open more skills later? Because the alien skill trees aren't available either.2016:

Now:

sullynathan

Arcane

vortex

Fabulous Optimist

When he threw the grenade at Earth, I thought it will recycle the planet too. :D

ciox

Liturgist

- Joined

- Feb 9, 2016

- Messages

- 1,405

There's also this, can see GUTS/Arboretum in it, nothing really new mechanics-wise, the radiation doesn't seem to do anything and "suit integrity" is still just armor despite all the status messages around it since it was tied to oxygen consumption at some point.

Hines

Savant

- Joined

- Jan 26, 2017

- Messages

- 258

PCGamesN have posted a breakdown of the abilities, which don't sound particularly exciting. :/

Human abilities

Scientist

“Use knowledge of science, medicine, and specialized lab equipment to your advantage.”

Hacking (levels 1 - 4)

Metabolic Boost

- Bypass security measures on computers and robotic systems.

Physician (levels 1 - 2)

- Doubles both the duration of the Well Fed bonus and the health gained by consuming food.

Necropsy

- Your knowledge of medical practice increases the effectiveness of Medkits.

Engineer

- Recover more valuable organs from Typhon remains. Typhon organs can be recycled for exotic material, which is used in the fabrication of Neuromods.

“Specialize in modifying your gear, repairing, and crushing problems with your wrench.”

Leverage (levels 1 - 3)

Repair (levels 1 - 3)

- Lift heavy objects with ease and throw objects further. Thrown objects will damage enemies (at level 3, your brute strength can be applied to force open an unpowered door).

Gunsmith (levels 1 - 2)

- Lvl1 - Fix broken Grav Shafts, Fabricators, and Recyclers with Spare Parts.

- Lvl2 - Fix broken Turrets, Operators, and Electrical Junctions.

- Lvl3 - Fortify Turrets.

Suit Modification (levels 1 - 3)

- Allows use of Weapon Upgrade Kits to upgrade security weapons beyond modification level 1 (allows fully upgraded guns at lvl2).

Dismantle

- Upgrade your TranStar uniform with extra inventory space and allow installation of chipsets.

Materials Expert

- Break down equipment in your inventory into Spare Parts and recover Spare Parts from destroyed Operators or Turrets.

Lab Tech (levels 1 - 2)

- Increase recycling yield by 20 percent.

Impact Calibration (levels 1 - 3)

- Allows use of Weapon Upgrade Kits to upgrade non-standard tech weapons.

Security

- Lvl1 - Reduce stamina cost of wrench attacks by 25%.

- Lvl2 - Wrench attacks deal 50% more damage.

- Lvl3 - Attacking with the wrench has a 25% chance to do Bonus Damage.

“Boost your physical abilities, skill with firearms, and security tactics.”

Firearms (Levels 1 - 2)

Conditioning

- Increases damage with security weapons and increase chance to critically hit.

Toughness (levels 1 - 3)

- Increase your health to to 115 and your stamina to 105. Run, sneak, climb, and sprint 5% faster.

Stamina (levels 1 - 2)

- Increase your health, natural lifespan increased.

Mobility (levels 1 - 2)

- Increases stamina.

Combat Focus (levels 1 - 3)

- Increase overall movement speed. Run, sneak, climb, and sprint faster. (Lvl2 increases jump height).

Stealth (levels 1 - 3)

- Enter a state of Combat Focus for 10 seconds in which time slows around you and actions cost 50% less stamina (higher levels increase duration, lower stamina use, and increase damage).

Sneak Attack (levels 1 - 2)

- Lvl1 - Enemies take longer to detect you when you are sneaking or crawling.

- Lvl2 - Walk and run without making noise.

- Lvl3 - Sprint without making noise.

Typhon abilities

- Do increased damage to enemies while they are unaware of you.

We know less about these - Typhon abilities have to be learned by scanning aliens with the psychoscope, much as we once photographed Splicers in Rapture. As such, much of the Typhon skill tree remains a mystery to us - but what’s here is terribly tantalising.

Energy

“Harness the destructive power of electricity, fire, and kinetic energy.”

Kinetic Blast (levels 1 - 3)

Electrostatic Burst (levels 1 - 3)

- Create a physical blast that deals up to 50 damage and pushes away anything within 5 meters of the targeted area.

Electrostatic Resistance

- Create an electrostatic burst that deals damage to the targeted area. Additionally the burst disrupts electronic equipment, stuns robotic and biological targets.

Electrostatic Absorption

- Takes less damage from electric attacks and hazards, and negate stun.

Morph

- Absorb 50% of all electrical damage as psi points.

“Manipulate the psychoactive ether to change shape and dupe your enemies.”

Phantom Genesis (levels 1 - 2)

Telepathy

- Create a Phantom that will fight for you from a human corpse.

“Use your mind as a weapon or manipulate technology and objects at a distance.”

Backlash (levels 1 - 3)

- Create a shield for 20 seconds which prevents the next enemy attack from damaging you. Enemies that attack the shield are repelled.

https://bethesda.net/en/article/3QUOVPanDO4gOSKiQCgW8K/crafting-the-story-of-prey

Crafting the Story of Prey

For Creative Director Raphael Colantonio, inspiration hit while he was 40,000 feet above Earth. Which is only fitting, considering Prey is set on an alien-infested orbiting space station miles from our planet.

“I was on the plane, returning from a vacation, and it was a super long flight,” Colantonio recalls. “That’s when I wrote the main arc for Prey.”

But Colantonio’s quick start was just the beginning of the long journey to craft the deep narrative and richly realized world of Prey. Upon his return to his office in Austin, Colantonio brought in the team at Arkane Studios to flesh out his idea, to mold it, to adapt it, and to create everything from the alien ecology, to the space station design, to the supporting characters and dialogue. Along the way, several key contractors joined the studio to help with Prey’s story in a multi-year process that’s resulted in this epic sci-fi thriller full of surprising twists and thrilling turns.

“We had many long sessions with the level designers, discussing the game’s high-level idea,” says Lead Designer Ricardo Bare. At the same time, the studio worked with the art team developing the world itself, including a backstory that involved President Kennedy surviving the assassination attempt, a renewed focus on the space race, a cooperative effort with the Soviet Union, and the whole Neo-Deco vibe that defines the look and feel of Talos I. (And that’s not to mention the countless hours perusing research covering everything from real rocket science to pseudo-scientific studies on aliens and the paranormal.)

“It probably took a year before we actually came up with the narrative of the 60s, along with the all of the history and layers that became the pillars of the game,” Colantonio says.

“It was a long time before we were even creating dialogue,” Bare adds. “We initially focused on structure with level designers, motives, objectives, backstory with the artists. And then we were just grinding on our one-page synopsis over and over to get it refined.”

Enter Avellone

Along the way, Arkane looped in some outside voices as well. Harvey Smith, who was now fully focused on Dishonored 2 at Arkane’s Lyon studio, helped come up with a rationale for the existence of the Typhon aliens. Austin Grossman, an award-winning writer who worked on System Shock along with Dishonored and Dishonored 2, helped refine some of the early ideas in the original synopsis, including how main character Morgan Yu would uncover his missing memories. And then the team reached out to industry legend Chris Avellone (Fallout 2, Fallout: New Vegas, Baldur’s Gate: Dark Alliance) to join the writing team – which was a dream come true for Ricardo Bare.

“Before I was even in the games industry, one of my favorite games of all time was Planescape: Torment,” Bare says. “There were several other games I really liked that had kickass characters as well. I later realized they were all written by the same guy.” Bare met Avellone for the first time when they were on a panel together at PAX East in 2013. “It was a cool fanboy moment for me,” he smiles.

The admiration was mutual, and Avellone jumped at the chance to work with Arkane. Colantonio initially reached out to Avellone, but he was busy at the time – something Avellone wanted to rectify as soon as his schedule cleared up. “I dropped Raf a line and asked if he’d still be interested in working together,” he says. “It was a quick conversation, and things went from there to visiting the studio, seeing the pitch for the game, the pillars – both for the game and the studio’s approach to development, which shows in their titles – and dissecting the design docs.”

Avellone also looked forward to reuniting with his former PAX co-panelist. “I already knew Prey’s lead designer and lead writer Ricardo Bare from previous narrative gatherings and I’d read his work and enjoyed it. (Among his many talents, he made dwarves terrifying in his novel Jack of Hearts.) So working with the two of them and the Arkane crew seemed like a great opportunity – and it was.”

Characters with Character

Avellone immediately set to work – not just on offering his feedback and insights into the story but also in developing many of the side-characters and side-quests. “I’ve always admired Chris’ characters,” Colantonio says. “He’s created some really cool characters with some intriguing dilemmas. They often lead to quests where you as a player find yourself in weird situations where you don’t know exactly what to do – and whatever you do, you feel like you didn’t quite make the right decision.”

“Aside from a collection of minor characters, I worked on about five other major characters and their arcs in the game,” Avellone says. Among his favorites: neuroscientist Dayo Igwe and Chief Systems Engineer Mikhaila Ilyushin. “Their arcs have some of my favorite moments.”

But don’t think of Dr. Igwe and his cohorts as “just” side characters. Because Morgan Yu is a bit a cipher – a person whose past is hazy, and whose memories are missing – these other characters play a major role in discovering who you are. “They help inform the context of the player’s choices from their own perspective,” Avellone says. “They also flesh out the larger universe of Prey, and the impact that Talos I and TranStar have on the world from a scientific, social and military perspective. Each NPC also has their own take on Morgan Yu as well, which the player may need to puzzle out.”

“When you encounter side-characters like Mikhaila and Igwe, they know things about you,” Bare adds. “They know things about the former Morgan. In conversation with them, they’ll mention those things and they’ll reveal something about who you used to be. Which is a fun way to find out about yourself.”

Action and Reaction

Avellone was also a great fit for Arkane because his general approach closely mirrors Arkane’s core philosophy. “He uses a different vocabulary than we do, but he’s essentially talking about the same thing,” Bare says. “He came in talking a lot about ‘reactivity,’ which is the idea that when I do something cool or interact with these characters or do something in the world, I want the characters to react to that. I want the things that I do to have a ripple effect. And that meshes really well with what we’re trying to do with Prey.”

“In terms of narrative structure, it was interesting to bring my previous role-playing narrative sensibilities and reactivity to an FPS,” Avellone adds. “I was both able to share a lot and learn a lot at the same time.”

Avellone’s quirky humor also made him a great fit for Prey’s story. “He always has a little bit of dark humor in his characters and in his dialogue,” Colantonio says. “It fits the dark mood of our game.”

Avellone cites the move Aliens as an inspiration for his approach to writing. “At its core, Aliens is an action-suspense movie. It rarely lets up,” he says. “However, what some people fail to appreciate is that because of the writing and the characters, Aliens is one of the funniest movies ever. Better, the comedic moments ‘fit’ because of the character reactions and the empathy for their responses – Bill Paxton, especially, but it applies to almost everyone. They’re genuinely funny bits, even in the context of a horror-suspense movie, and they’re timed with the narrative pacing.”

For Avellone, Prey is a lot like Aliens in that regard. As suspenseful as the game can be, Prey needs to have moments that break the tension in order to keep the experience from flattening out. “I think it’s good to include humor as long as you don’t undermine the experience, and walking that fine line I think is what Prey does successfully.”

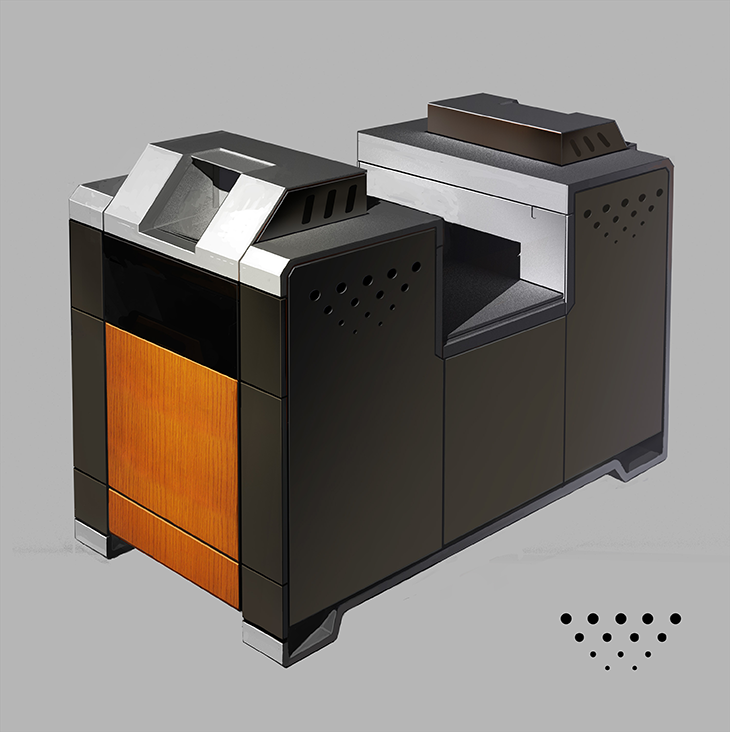

Referencing the Reployer

A perfect example of this humor can be found in a lowly device called the Reployer. Designed by an artist at Arkane, the Reployer started appearing on desks and in offices throughout Talos I – but no one could tell anyone what exactly it did. Was it a printer? A space-age fax machine? A photocopier? Again and again in team meetings, someone would inevitably ask about it, and no one would have an answer.

“We almost cut this from the game three times,” Colantonio says. “I even had a few ‘fights’ with [Lead Visual Designer] Manu [Petit], telling him I never want to see that thing again – until we eventually turned it into a joke and said, ‘What if no one aboard the space station knows what that object is? Let’s give it an obscure name like Reployer and let’s have people talk about it in emails.’”

After Arkane transplanted their real-world confusion into the game itself, the Reployer became a recurring joke referenced in emails and dialogue between TranStar employees. Without missing a beat, Avellone incorporated this into his own work on Prey. “Chris picked up the joke in the dialogue he was writing too,” Bare says. (Keep an ear out for a moment between Mikhaila and January in Morgan’s office to catch a particularly funny Reployer exchange written by Avellone.)

It’s these kinds of exchanges that breathe even more life into a dark story and deep world. And it’s one of the main reasons Avellone was able to add so much to Prey’s already rich narrative. As for Avellone himself, this was a stellar collaboration. “They set clear expectations, gave clear feedback, and were always willing to listen and consider any narrative or design point I brought up,” he says. “Even though I was on contract, I felt very much part of the studio and the process – Arkane made me feel welcome.”

ciox

Liturgist

- Joined

- Feb 9, 2016

- Messages

- 1,405

PCGamesN have posted a breakdown of the abilities, which don't sound particularly exciting. :/

Yeah, still those are the abilities that are unlocked at the very start of the game, once you find the Psychoscope some additional nodes appear in the Scientist tree for upgrading your Psi (maximum psi points?) and your Psychoscope (number of Scope chipsets)

PC players always get a free demo. About the whole game.So the only platform that really needs a demo is not getting it.

They'd be stupid to release a PC demo and give the cracking scene a head start. See the RE7 Demo and how Denuvo was cracked shortly after.

![Glory to Codexia! [2012] Codex 2012](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_slushfund2012.png)

![The Year of Incline [2014] Codex 2014](/forums/smiles/campaign_tags/campaign_incline2014.png)